How Louise Bourgeois spun her father’s affair with her governess into a cannibalistic artwork

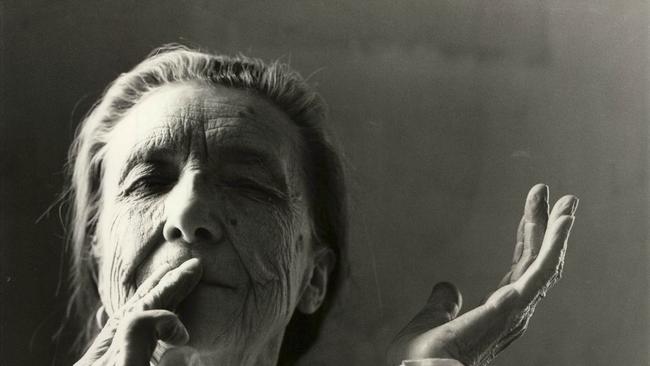

Louise Bourgeois’s feelings of rage towards her father – and her governess – were reflected in her art as she emerged from a traumatic childhood to become, late in life, one of the world’s leading artists.

When Louise Bourgeois was 10, a young British woman, Sadie Richmond, was hired as an English tutor for her and her two siblings. Richmond would live with the family of French tapestry repairers for almost a decade. And for most of that time, she conducted an affair with her employer, Bourgeois’s father, Louis.

Louis was a serial cheat, and this affair was carried on inside the family home. This left the young Bourgeois with feelings of a “double betrayal’’ by her father and her tutor. She also felt resentment towards her mother, Josephine, because “my mother tolerated it’’.

Her feelings of rage towards her father – whom she at other times adored – were later reflected in her art as she emerged from the emotional debris of a traumatic childhood to become, late in life, one of the world’s leading artists. “I’m a prisoner of my memories … and my aim is to get rid of them,’’ said the French-American sculptor, print-maker and painter, who used her work to help purge her obsessive, unhappy memories of her childhood.

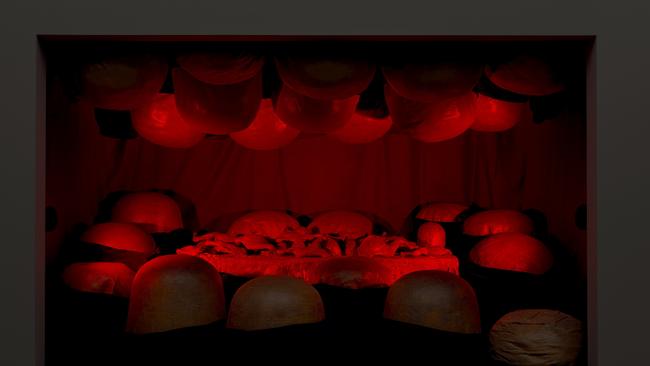

Bourgeois’s fury with her dad – and to know-it-all patriarchal figures more generally – arguably found its strongest expression in her confronting 1974 work, The Destruction of the Father. A resin and wood sculpture bathed in red light, it features body parts cast from chicken legs and lamb shoulders. According to an accompanying narrative, a mother and her children become fed up with the father’s dinner-time pontificating, so they rip him up and eat him.

Alongside the Grimm’s fairytale-style horror, there is sly humour at work in this piece, says Philip Larratt-Smith, who has curated eight Bourgeois shows and knew the mercurial artist in the years before she died in 2010, aged 98. He says: “It’s an intense, lurid, fantastical piece that’s not without its comedy. There’s a dark humour in a lot of Louise’s work that often gets left out when people talk about it. It’s not always all Sturm und Drang.’’

Larratt-Smith is a curator from the New York-based Easton Foundation, which administers Bourgeois’s legacy, and he says “there is no question the (mistress) situation was traumatic for Louise’’. Her father’s betrayal was “an influence on her art across many layers at once. She was critical of her father for having this affair, but she was also critical of her mother for tolerating it. And she was critical of Sadie the mistress … She thought of Sadie as a rival for her father’s attention.’’

Even so, he feels the story of the traumatising effects of her father’s infidelity can be exaggerated: “Louise was a master storyteller. I think she tells her story with the intensity of a Greek myth.’’

Larratt-Smith is in Australia to oversee the installation of the biggest display of the artist’s work mounted in this country. Titled Louise Bourgeois: Has the Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day? this landmark survey at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney will feature Bourgeois’s career-defining works, including The Destruction of the Father, the elegant – and headless – bronze sculpture Arch of Hysteria (1993) and her internationally-renowned spider sculptures, Spider 1997 and Maman 1999.

Maman is a tribute to the artist’s mother, the mainstay of the family’s tapestry business and – like Bourgeois’s arachnid – an industrious and talented weaver. Constructed from bronze, steel and marble, it stands more than nine metres high and will be installed on the forecourt of the art gallery’s south building.

When Tate Modern opened in 2000 on the banks of the Thames in London, Bourgeois was allocated the first show there. Facing out over the water towards St Paul’s Cathedral, Maman’s power to entrap or protect astonished many, including Oscar-winning filmmaker Jane Campion. In the AGNSW exhibition catalogue, Campion reveals that Bourgeois is “my art idol’’ because of her “uneasy mix of beauty, truth-sharing, dark hidden memories, pain, shame and comedy. She’s gone to the depths.’’

Bourgeois, who has had shows at Tate Modern, MOMA and the Hermitage in St Petersburg, created a series of monumental spider sculptures, earning her the nickname “Spiderwoman”. Her other recurring themes – explored through materials ranging from bronze, marble and steel to latex and textiles – included domesticity, motherhood, sexuality, the body and the power of the unconscious.

The AGNSW survey will span seven decades of work, from her sculptures of the 1940s – elongated, Giacometti-like human figures – to her overtly sexualised – and distorted – genitalia and body parts. Nature Study 1984-94 is a pink flesh coloured sculpture with six breasts and animal feet, while some of her sculptures of genitalia are neither entirely male nor female, and seem to be atrophying before our eyes. In 1996 she made a handkerchief embroidered with the words: “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.’’

This show is the first exhibition by a solo artist to be mounted at the AGNSW’s new, multi-storey building designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architects SANAA as part of the $344 million Sydney Modern project. It’s curated by Justin Paton, the gallery’s head curator of international art, who says: “Naturally, it’s a momentous decision – who gets to have the first monographic exhibition in a new museum. And it’s very fitting that it is Louise, because not only is she one of the most important artists of the 20th century, her influence extended into the 21st century.’’

Although she was associated with movements including abstract expressionism and surrealism, she wasn’t a signed-up member of any of them. In fact, broad public acknowledgment of her extraordinary talent and searching intelligence only came when she was in her seventies. As Larratt-Smith notes: “Louise is an artist to whom recognition came relatively late in life with the landmark exhibition in 1982 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That was the moment when Louise went from being an artist’s artist to a more general appreciation of her significance. … She went from strength to strength, constantly innovating, changing form, changing material, and so I think that absolutely Louise has emerged as one of the most important artists of the last century. It’s been said that she straddles modernism and post-modernism.’’

She was reluctant to be known as a feminist artist, even though it was feminists who lobbied for her MoMA show. Says Larratt-Smith: “She felt that feminist art was more like political art and often became very dated very quickly. In her personal life she was absolutely a feminist.’’

Bourgeois married American art professor Robert Goldwater after a three-week romance in Paris and they moved to the US in 1938. Despite Bourgeois suffering from acute depression, agoraphobia and insomnia, the couple raised three boys and the marriage lasted until Goldwater’s death in 1973.

In Paris and later in New York, Bourgeois knew art world giants including Duchamp, Miro and Rothko. She complained that only “rich women” were welcomed by the surrealists, which she considered “an insult’’.

Because she worked with radically different materials and in different styles “she was very difficult to classify,’’ says Larratt-Smith. “That is something that makes her very relevant today. But it was certainly an obstacle earlier on. She described herself once as a lonely long distance runner.’’

She once said the artist’s condition was “tragic” and “incurable”. I put it to Larratt-Smith that her life seemed to be a never-ending struggle to achieve mental equilibrium, if she wasn’t working. “I think that’s a fair description,’’ he says.

She tried to commit suicide after her mother died when she was 20, and she fell into a paralysing depression after her father passed away. Says Larratt-Smith: “Louise was in psychoanalysis from 1952 until 1967 — quite intensive, four to five times a week with the same analyst.’’ He has chosen nine dream recordings for the exhibition that were “part of that process’’, and that explore the connection between her conscious and unconscious selves.

He adds: “When we talk about the deep depression of the 1950s, this was a period where she struggled to leave the house because she had intense agoraphobia. She had terrible insomnia, so she would often be up all night.’’ She was also caring for the boys. “I think it was very difficult for the children,’’ the curator reveals.

She could also be the embodiment of mischief. A famous 1982 Robert Mapplethorpe image features the then 71-year-old smiling broadly and wearing an elaborate, fake fur jacket. Tucked under her arm as if it is of no more consequence than a brolly, is a sculpture of a gigantic penis with bulging testicles.

Writer Chris Kraus met her during the 1970s and remarks in the catalogue that “she was not nice. It was very clear that anything that transpired was transpiring for its usefulness and interest to Louise. There was no bland altruism at work.’’

Larratt-Smith agrees. “Louise was ruthless,’’ he says. “When I knew her she was 89. … Every relationship and every situation had to feed into the work. I think she felt that anything that didn’t feed into the work was extraneous and could be dispensed with.’’ This meant that when working for her, “Louise could be a handful. You see it in the work – there’s a side that’s very sweet and there’s a side that’s very monstrous. You never knew what Louise you were going to get.’’

Tiny and fierce, she lived in the same New York townhouse for 50 years and worked until the final days of her life.

She conducted salons in a cramped room with younger artists to critique their work. These sessions, dubbed “Sunday, bloody Sundays” by one wit, were not for the faint-hearted. In one meeting filmed by the BBC, a female artist says her painting is about the torment of being an artist. Bourgeois objects: “It is not a torment to be an artist. The premise is idiotic. It is a privilege.’’

Larratt-Smith says Bourgeois was “an extraordinary writer’’. She wrote about psychoanalysis and feminism and “to my mind she’s one of the great artist writers of our history, along with Van Gogh and Delacroix’’. He is a planning to publish a volume of her psychoanalytic writings in 2026 with Princeton University Press. “The work is very rich and it’s endless. It just keeps pulling you in,’’ he says.

He notes she could be scathing about analysts, declaring that some thought of themselves as “gods’’, even though she needed them. “Ambivalence is an important psychological state for Louise,’’ says Larratt-Smith.

We see this play out in the exhibition, with one section titled good mother/bad mother. Explains the Easton Foundation curator: “In the 40s and 50s I think she found it very difficult to be a good mother to her children. … She felt a conflict between her duties as a mother, as a wife to Robert, with her ambitions as an artist. … The family dynamic was always complicated.’’

Her two eldest sons have died, while her youngest, Alain, is a foundation trustee. “Alain is a trustee of the legacy but I do not think it was always easy to be Louise’s child.’’

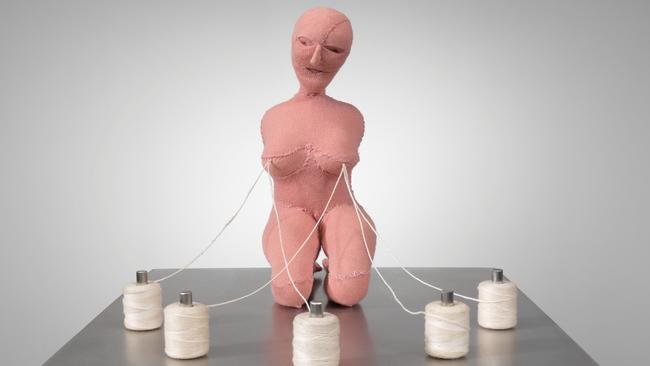

According to Paton, “part of what makes Louise so extraordinary is that she takes on the subject of motherhood in all its complexity and difficulty. And she doesn’t shy away from grasping the shifting emotions that many women feel; certainly that she felt in respect of her children – murderous impulses, conflict, psychic splitting.’’ Umbilical cord 2003 depicts a pregnant, crudely-stitched woman with a transparent womb. It’s an apparently serene sculpture … but does the woman’s lack of arms signal a sudden lack of control over her life and destiny?

For the exhibition, more than 120 works will inhabit two major spaces: the crisp, white rooms of the SANAA building’s major exhibition gallery, and the shadowy Tank, a disused Second World War fuel bunker downstairs. AGNSW director Michael Brand sees this as “an extraordinary opportunity to dramatise the tensions, the contradictions, and the powerful psychological oppositions that drove Bourgeois’ art’’.

The exhibition title comes from a 1995 quote by Bourgeois. It references her insomnia, ferocious work ethic and the extremes of emotion within her art. Says Paton: “She said that she saw the emotional polarities of her own mother and father within herself: her father was very emotive and charismatic, while her mother was exceptionally steady and rational. You see this time and again in her work – the way she moves from something very geometrical and calm and ordered, to something quite furious, chaotic and emotionally turbulent.’’

Larratt-Smith says Bourgeois was so single-minded and driven, “when she wasn’t working, it could be problematic for her … In many ways, she lived to work.’’

Louise Bourgeois: Has the Day Invaded the Night or Has the Night Invaded the Day? opens today at the Art Gallery of NSW.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout