Interview: Sigur Ros frontman Jonsi on Obsidian, a volcanic exhibition at Mona

His music with Icelandic rock band Sigur Ros moves people to tears, his homemade perfume costs $300 a bottle and now this talented artist wants to take you inside a volcano.

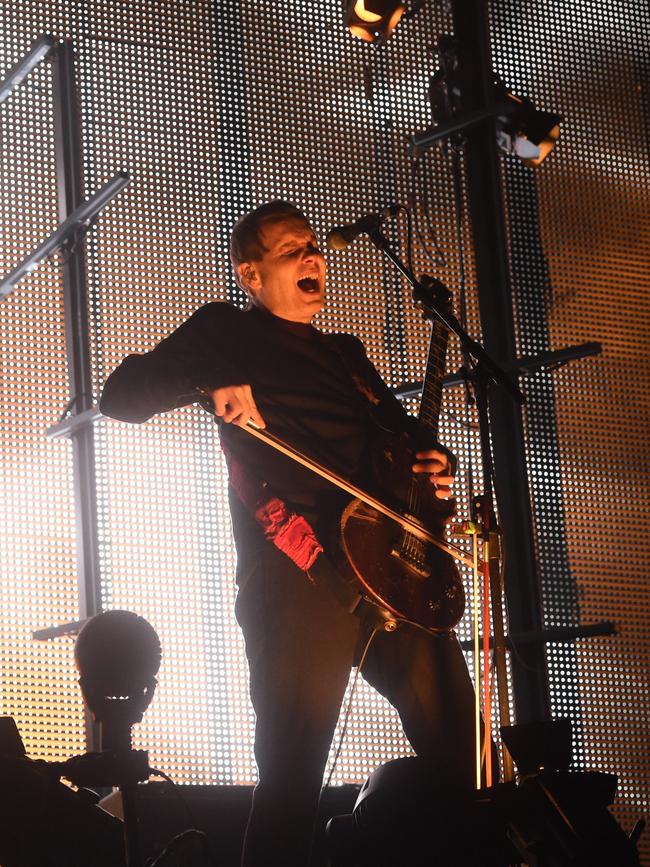

A rake-thin, elfin man singing in a beautifully clear falsetto while wielding an electric guitar and a cello bow. Sprawling, lengthy songs that contain a vast dynamic range between their quietest moments and blisteringly loud crescendos. Regular lashings of orchestral strings, horns and choral embellishments interwoven with plaintive piano melodies and driving drums and bass.

When the constituent components of the music created by Sigur Ros are listed, it doesn’t sound much like a project that could be commercially viable in the band’s homeland of Iceland, let alone anywhere else.

Yet since forming in 1994 and issuing its breakthrough second album Agaetis Byrjun in 1999, the experimental post-rock act has become one of the strangest modern bands to achieve global fame, albeit of the cult variety: millions of indie music fans are familiar with its sound, which came to prominence in the early 2000s.

You’ve probably heard it for yourself, too, given how often its distinctive textures – showcasing both icy desolation, and shimmering with life-affirming warmth – have been used as a soundtrack for nature documentaries, or to accompany dramatic moments on screen.

The band’s ardent devotees are legion, including in Australia, where it has toured eight times, regularly filling theatres and playing at big festivals such as Splendour in the Grass, where it has been booked three times since 2008.

Other than the frontman’s unorthodox decision to play guitar with a cello bow — to help sustain his searing notes and chords for longer than if he was using a shorter violin bow — what’s perhaps most strange about Sigur Ros is the way its vocalist came to sing in a style that alternates between Icelandic and a made-up language called Vonlenska, or “Hopelandic”: an emotive set of vocalisations he has described as “a form of gibberish vocals that fits to the music”.

Like his Nordic compatriot artist Bjork, Jon Thor Birgisson is known by a mononym, Jonsi. And like plenty of other famous rock frontmen – Eric Clapton and Josh Homme among them – he only stepped up to the microphone in the first place because nobody else wanted to.

“I never look at myself as a singer, as funny as that might sound,” he tells Review. “It was a necessary evil to begin with, and I just started singing in falsetto, so that I was singing higher, to sing over my bandmates. I was singing into guitar amps in the beginning, and nobody could hear themselves.

“I never think I’m a professional singer,” Jonsi says with a laugh. “But I love it; the human voice is so incredible. It’s the prime mover, I think, for people.”

Sigur Ros — pronounced “sigger rose,” meaning “victory rose”, and also the name of Birgisson’s sister — makes music that touches people deeply; its concerts are frequently described as transcendent experiences. The hooks don’t come thick and fast but, if you’re paying attention, it’s almost impossible not to be moved to tears by the sheer power and harmonic beauty of what these musicians can conjure.

The band last toured here in August 2022, when it played a career-spanning set split into two halves. Watching the musicians then, a question occasionally bubbled to the surface amid the delicate soundscapes: is eliciting emotion in the listener a goal for Sigur Ros, or an accidental side-effect?

“It’s definitely not the premeditated plan,” Jonsi, 48, replies. “You make music and it moves you, and that’s the goal, I guess: to move yourself. It’s hard to do, but I guess you want to move people.

“It’s very selfish: making music because you want to make yourself feel good, personally, and making music with somebody – creating something from nothing – is extremely satisfying,” he says. “If it moves somebody else, that’s just a bonus thing that happens.”

When Review connects with Jonsi in August, he’s at home in Los Angeles, on a brief break between tours. Sigur Ros recently issued its eighth album, titled Atta – Icelandic for “eight” – which marked its first studio release since 2013, following the return of multi-instrumentalist Kjartan Sveinsson to the fold after nine years away.

This core trio – completed by bassist Georg Holm – and their touring drummer Olafur Olafsson have been performing in Europe, playing songs new and old, while accompanied by Wordless Music Orchestra; Jonsi and co will soon take the show on the road around the US, too.

Asked how the new material is sitting among the well-honed crowd favourites, he replies, “It’s heavily orchestra-influenced, so it’s nice to play. And it’s nice to actually play with an orchestra: you feel like you’re in this cocoon of talented musicians around you, so you have more space and breathing room to, like, f..k up. You’re not quite the centre of attention, which is nice: there’s 40 other people around you.”

The reason we’re talking, though, is because Hobart museum Mona has purchased an exhibition by Jonsi titled Hrafntinna (Obsidian), and will soon begin showing it inside David Walsh’s world-famous art collection, with the creator himself planning to travel to oversee its installation in late September. Unsurprisingly given his artistic path to date, it’s a rather oddball concept with an unusual backstory, which Jonsi – who was born blind in his right eye due to a broken optic nerve – describes thus.

“It’s based on the Icelandic volcano Fagradalsfjall that erupted in 2021,” he says. “It was right in the middle of Covid, so I couldn’t get back to Iceland to see it.

“I just wanted to be inside the volcano, when I made this. It’s based around 200 speakers in a circle around you; a 360 (degree) kind of spatial sound. There’s two choir pieces, and two more experimental, soundscape parts in it.

“It’s hard to document or capture in media, because it’s pretty dark in the room; it’s hard to explain, somehow,” he says with a laugh.

Previously installed at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York, Obsidian was also shown at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Canada until last month, when it was packed up and shipped to the bottom of the globe.

Asked why he wanted to visit the volcano – which had been dormant for more than 900 years, while situated 60km southwest of Reykjavik – Jonsi replies: “I think it was just the thing, what is it, FOMO? Fear of missing out? Because I was seeing it through my family, my friends – everybody was going there and was like, ‘Oh my god, it’s incredible. It’s the most amazing thing I’ve seen in my life!’ All these really intense reactions from people to see the pure, brute force of nature, spewing lava out from the earth. It’s really intense; people were describing the smell and the sounds.

“I just wanted to go and be there, and experience it,” he says. “But it’s kind of nice: you see all this stuff, you see pictures and videos of it – but then you kind of create your own (picture) of how it’s supposed to be, how it’s supposed to sound or smell, which is also interesting to me.”

As the artist tells it, a happy confluence of events led to its creation. He had booked an exhibition for the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, and had begun visualising a dark room, but hadn’t gone much further with the concept.

At the same time, he was working on a solo album, also titled Obsidian. “Then the volcano happened and then I was like, ‘OK, of course. That makes sense’,” he says. “I used some of the music from the album in the exhibition, and vice versa. It all went hand-in-hand, somehow.”

With a friend in downtown LA, he used a computer program to model the dimensions of the room and work on an ideal speaker placement for the spatial sound effect he had in mind. But why 200 speakers, exactly?

With a laugh, he replies: “We decided how big the circle should be – and then you try to slap as many speakers as possible in that circle. We have 15 stands, and then on each stand is 13 speakers, so there’s 195 speakers total.” As well, there’s a main seat in the middle of the room, under which are placed several subwoofers. “It’s nice – you get the bass up in your ass,” he says.

In addition to the look, sound and feel of the room, Jonsi gave plenty of thought to how his simulation of a volcano should smell, too. “With the scent aspect, I was really curious,” he says. “When you walk in (to the exhibit), it’s the only essential oil that’s harvested from the ground: it’s fossilised amber oil, and it’s extremely smoky. An amazing smell.”

Amazingly expensive, too: he’s not joking about the oil being harvested from the earth, and its market price is about $2000 per kilo. As for how he landed on fossilised amber as the nose profile, well, Jonsi is perhaps unique among rock stars alive today in that he is deeply invested in the art of perfume-making.

“I was thinking, ‘I probably should just make my own blend …’ because I have a perfumery organ at my place, and probably 1000 different bottles of essential oils and other aroma molecules,” he says. “I’m all into perfumery and stuff. But then I saw this fossilised amber, and I thought it was interesting to have just one oil throughout the whole thing.”

Perfumery organ? By this he means his blending table, which is built out of the remnants of an old organ. It’s an unusual thing for anyone to have inside their home, especially considering it’s only a hobby compared to the main thing he’s known for, which is making music. He’s got a home recording studio, too – but “the perfumery is bigger than the music space,” he says with a laugh.

It’s a hobby, but also a business: in Reykjavik, his three sisters and father run a store named Fischersund, which stocks a range of homemade candles, incense and Jonsi’s blends. His first and best-selling fragrance is named No.23, and contains notes of “aniseed, black pepper, tobacco seeds and Icelandic Sitka spruce”. (Cost: 24,900 Icelandic Krona, or about $A292, per 50ml.)

Asked which of the two adjacent rooms in his home is more likely to draw him in on any given day, he replies, “Perfumery, definitely. I haven’t been making music for some time – but I’m doing another exhibition in November, so I need to, like, start cracking, making more stuff.

“There’s just something about perfumery that is so extremely difficult to me,” he continues. “It’s probably one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done in my life. I’ve been doing it for 13 years, and you make hundreds of different blends, and there’s so much material, there’s so much stuff to learn; it’s a bottomless pit of disappointment, sometimes.”

“But there’s something about it, because you learn from all your mistakes, and you’re always learning something new or discovering something. It’s endless. It’s crazy. It’s really complicated, but it’s so fun. I’m addicted to it, somehow: I try a blend, put it in a spray bottle and spray it on myself, or on my boyfriend, just to try it and see.”

The problem with perfumery, though, is this: “You always have to wait, to let things marinate,” says Jonsi. “It’s such a f..king slow thing. I’m a very spontaneous person; I want to see results right away. It’s so frustrating: you need to make a blend, and preferably let it marinate for a month, or three months, and then come back to it and see how it is. I have no patience for that.”

At this, Review can’t help but crack up laughing: here’s the frontman of a band globally known for making patient art for patient people, revealing himself to be the exact opposite of that trait. With a chuckle, he replies, “It’s true: our music is really f..king slow. That’s sometimes how it is; opposites attract, I guess.”

One night in Paris about 20 years ago, Sigur Ros played a concert while accompanied by a choir from his homeland named Schola Cantorum. Together, they performed an old Icelandic poem called Odin’s Raven Magic.

Afterwards, in a celebratory mood after a great show, the musicians and crew headed to a bar, where the singer was struck by a moment of boozy inspiration: he offered to buy a shot of vodka for the entire choir if they agreed to encircle him and sing his favourite Icelandic hymn.

Which is how Jonsi ended up sitting on the floor in a Paris bar, in a drunken state of bliss, as about 30 people pointed their instruments at him, opened their mouths and fulfilled his request at full volume.

“There’s nothing like having a whole choir sing to you, in a circle,” he says, smiling at the memory. “It was incredibly beautiful. So the choir part of this Obsidian piece is definitely inspired by that, to have people sing from different speakers at you; to surround you with voices. That idea of the circular form, and the 360 sound coming at you from all sides? It’s extremely satisfying to me. You don’t really control the sound, or where it comes from. It’s a very pleasurable thing to do.”

So if you find yourself moved to make your way to Mona, enticed by the idea of being inside Jonsi’s imaginative depiction of what a volcano sounds, smells and feels like, keep that circular choir image in mind.

As for the vodka? You might have to bring your own.

Hrafntinna (Obsidian)will be on display exclusively at Mona from September 30 to April 1.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout