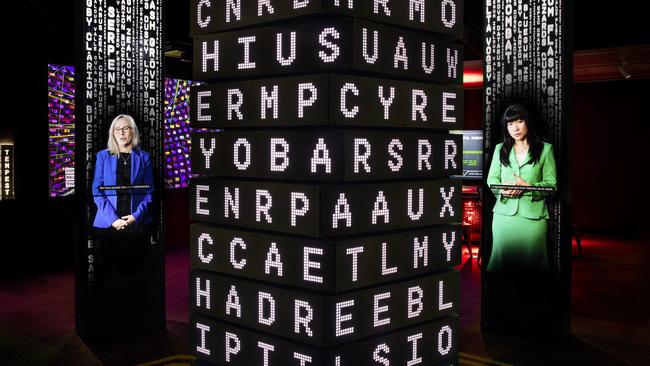

Cracking secrets and ripping yarns in Decoded

It may seem strange to mount an exhibition about an intelligence agency whose work is, by definition, highly confidential. On the other hand, a large part of its history is declassified and its general mission today is a matter of public knowledge.

It may seem strange to mount an exhibition about an intelligence agency whose work is, by definition, highly confidential. On the other hand, a large part of its history is declassified and its general mission today is a matter of public knowledge. The Australian Signals Directorate, formerly Defence Signals Directorate, is one the branches of Australia’s intelligence services: ASIO deals with domestic security, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service with foreign missions, and ASD with the analysis of information transmitted originally by radio and today predominantly over the internet.

An exhibition is also no doubt a useful way to alert potential recruits to the career opportunities that an organisation of this kind can offer to people with a range of skills not always fully appreciated elsewhere in Australia today. For example, ASD obviously wants people who are good at cyber technology, coding and hacking. But it also needs people who understand international relations, foreign cultures and foreign languages.

As an example of the importance of cultural understanding, when the Americans were at war with Japan, they commissioned prominent anthropologist Ruth Benedict, author of a classic study of the influence of culture on psychology, Patterns of Culture (1934), to produce a cultural survey of Japan so they could understand the people with whom they were dealing. This became another classic, if much debated book, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946).

Recent experience in the Middle East has confirmed yet again the dangers of becoming involved with peoples whose way of life and fundamental assumptions you do not understand.

Who acquires this kind of knowledge? Students of history and anthropology, as well as specialised courses on foreign relations. Equally important, again, is an area chronically neglected in Australia, the study of languages. We often lazily assume everyone speaks English these days or we can use an interpreter. Anyone with any experience of travel or international business knows there is no substitute for learning even a modest amount of another people’s language. It is a sign of respect that immediately breaks barriers and creates good will.

But it is not hard to see how much more important languages are in intelligence. You need to be able to read newspapers, websites, social media feeds, even handwritten notes or graffiti on a wall that will not be neatly printed for a beginner’s benefit but scrawled carelessly and in haste; you need to be able to understand the spoken language in all its registers, from formal to dialect, colloquial or slang, spoken too fast and poorly enunciated. And you may need to decode these messages in encrypted form.

This is where the story begins in the exhibition, with the famous story of the German Enigma machine in World War II and the cracking of the code by the British under Alan Turing’s leadership at Bletchley Park. Enigma encrypted messages in a code that changed every day so that decrypting one message would be no help in dealing with the next one.

Turing devised what was in effect an analog computer to break the code infinitely faster than any human mind. But of course decrypting a German message would be of little help if you did not have a perfect understanding of the German language. Hence, incidentally, Ewan McGregor’s first professional acting role as a young Russianist in military intelligence in Dennis Potter’s British television series Lipstick on Your Collar (1993).

During the war, Australians were involved in the even more difficult task of deciphering encrypted messages in Japanese, a language much less familiar to educated Australians than German. The exhibition includes a photograph of Captain Eric Nave, described a “code-breaking prodigy”, who later was employed in cryptography when the Defence Signals Bureau, as it was then known, was formed in 1947.

During the war, however, Nave was joined by a couple of brilliant academics in ancient Greek and archaeology from the University of Sydney, Athanasius Treweek and Arthur Dale Trendall. Treweek, with remarkable foresight, had started to teach himself Japanese in 1937 and Trendall joined him from 1940 in studying Japanese codes. They were instrumental in decoding vital Japanese naval transmissions around the time of the Battle of Midway.

The exhibition includes a set of translations of encrypted Japanese, from the initial decrypted code to a phonetic translation into Japanese and finally an English version; the text is a report by the Japanese ambassador to neutral Sweden, addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo, and reporting on the failed attempt on Adolf Hitler’s life in July 1944. It includes some fascinating analysis about the Nazi party’s failure to gain the loyalty of the aristocratic officer corps of the Wehrmacht and the opinion that from the time of the failed invasion of Russia disaffected groups were planning the Fuehrer’s overthrow. No doubt even now similar elements in Russia are contemplating ways to eliminate Vladimir Putin; in the world of dictators, nothing fails like failure.

After this is a section on Islamic terrorism in Indonesia, with a dramatic artefact: the coat of arms of the Australian embassy, broken when a suicide bomber blew himself up in a truck and killed eight other people at our embassy in Jakarta in 2004. The remains of the coat of arms, mounted on the wall, immediately catch the eye because the emu is missing; we find it and some other fragments in an adjacent display case.

Next to this is an interesting display of medals and other material reminding us that distinguished service in secret activities is seldom publicly rewarded. There is a military medal for exceptional service to intelligence but, as one individual relates, he was awarded it in a confidential ceremony attended only by the governor-general and a couple of aides.

The only man ever knighted for services to espionage, as far as I understand, was the remarkable Sir Paul Dukes, master of disguise and an excellent Russian linguist who was able to infiltrate the Bolshevik party during World War I, wrote several books and later was a pioneer of yoga teaching in England.

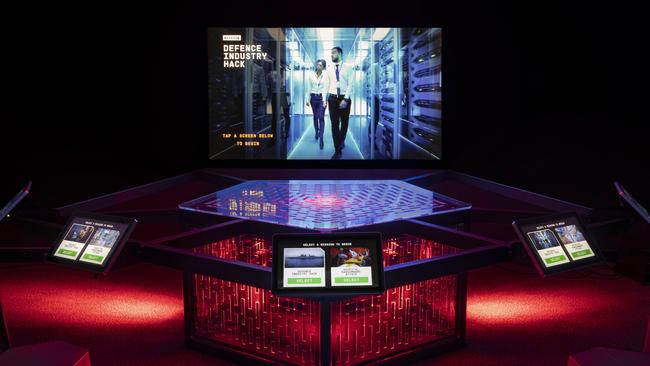

The remainder of the exhibition deals with the new frontiers of ASD business in the age of cyber warfare, with a demonstration of the Constellation application, which allows the department to analyse computer traffic all over the world and to trace cyber attacks, as well as an interactive game that allows viewers to take part in the simulation of a defence against two kinds of cyber attack, one a hack of a military system and the other a criminal ransomware attack on a hospital database.

Cyber warfare is undoubtedly one of the new frontiers of international conflict, which has several dimensions. In its most insidious and least overt form, it can be seen in the notorious interference by Russia, China and Iran in American political life.

But as numerous analysts have concluded, the most deleterious effect of such interference is not to support one or other political party but to exacerbate the partisan divisions within American society; by fuelling identitarian antagonism, for example, or anti-government paranoia, these interventions contribute to a long-term breakdown of the idea of being an American citizen or of having some sense of common national purpose.

At the level of overt cyber warfare, the most interesting case is the virtual war going on between Israel and Iran. These are the two cleverest and best-educated countries in the Middle East, each with vast strength in science, engineering and cyber technology. They used to be on friendly terms in the days of the shah but have been at loggerheads since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979.

Hostilities have taken conventional form with Iran’s Hezbollah proxies in Lebanon, and semi-conventional form with the daring assassinations of Iran’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, by remote control in November 2020, and then of Colonel Hassan Sayyad Khodai, of the Revolutionary Guard’s Quds Force, which deals with intelligence, spying and international operations. Khodai apparently commanded a unit that attempts to murder Israeli citizens abroad. He was gunned down in May by killers on motorbikes outside his house in Tehran, causing considerable angst about the ability of Mossad agents to operate effectively even in the capital.

But the cyber warfare events have been more interesting. An early case was the development of the Stuxnet virus to disrupt the nuclear plant at Natanz in 2009-10; in April 2020 an Iranian cyber-attack on Israel’s water supply was successfully countered, and the following month an Israeli cyber attack shut down the Shahid Rajaee port in the Straits of Hormuz for several days and wiped some databases used by the Revolutionary Guard. In June 2020 a massive explosion at the Parchin missile factory near Tehran was attributed to Israeli cyber attack.

The new field of drone warfare is a kind of hybrid of cyber and conventional, and last month the drone factory at Parchin was struck by an attack of suicide drones, launched within a 10km radius of the site.

There has also been an important cyber dimension to the war in Ukraine. More details will come out in time, but it seems that international hackers, including political opponents of Putin’s puppet in Belarus, have hampered the Russian war effort by cyber-sabotaging the rail system, among other measures.

These and other attacks give us some idea of the gravity of the threat. In the event of war with an opponent of any degree of sophistication, it is easy to imagine concurrent or pre-emptive attacks that could shut down everything from traffic lights and trains to water and electricity supplies, effectively crippling big cities. As with any kind of warfare, there is a race to develop both offensive and defensive systems.

The last item in the exhibition is a sobering reminder of how quickly computer technology has advanced. We can probably all remember the beginnings of the internet about three decades ago, the slowness of downloads and the limitations on data storage. The supercomputer in the exhibition is almost a decade earlier, dating from 1986.

At the time, it was a significant investment for the Australian government but it enormously enhanced our ability to break codes among other things.

Today, however, as the commentary explains – these recordings come on overhead automatically when you stand on a designated spot in front of a display case – your iPhone has 2000 times the processing speed and 50 times the storage capacity of the supercomputer, while operating on a minute fraction of the huge amount of power it required.

In other words, anyone from anywhere in the world, sitting in a cafe, a train or at home, has cyber capabilities that exceed those of giant corporations and even governments a generation ago; the proliferation of weapons in the Iron Age, or more grimly the ubiquity of guns in the US today are perhaps analogies for this extremely dangerous situation.

Decoded: 75 years of the Australian Signals Directorate

National Museum of Australia to July 24

Story of the Moving Image

Australian Centre for the Moving Image

New permanent exhibition

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout