Christopher Allen, critic in the frame

As he launches his new Companion to Australian Art, Christopher Allen says he is a compulsive teacher, whether in the classroom or in the pages of The Australian.

As Christopher Allen strides across the quadrangle at Sydney Grammar School, a senior boy greets him with a friendly hello. “Good afternoon, sir,” he says.

Allen is better known to readers of The Weekend Australian as an art critic, and for his weekly columns that combine vast erudition with sometimes bracing assessments of exhibitions, galleries and artworks.

But in his day job, Allen is a senior master at Sydney Grammar, one of the nation’s oldest schools and the alma mater to prime ministers Edmund Barton, William McMahon and Malcolm Turnbull. Allen himself is an old boy, having completed his schooling in Sydney after his earlier years at schools in Vietnam and Japan, where his father was posted on business.

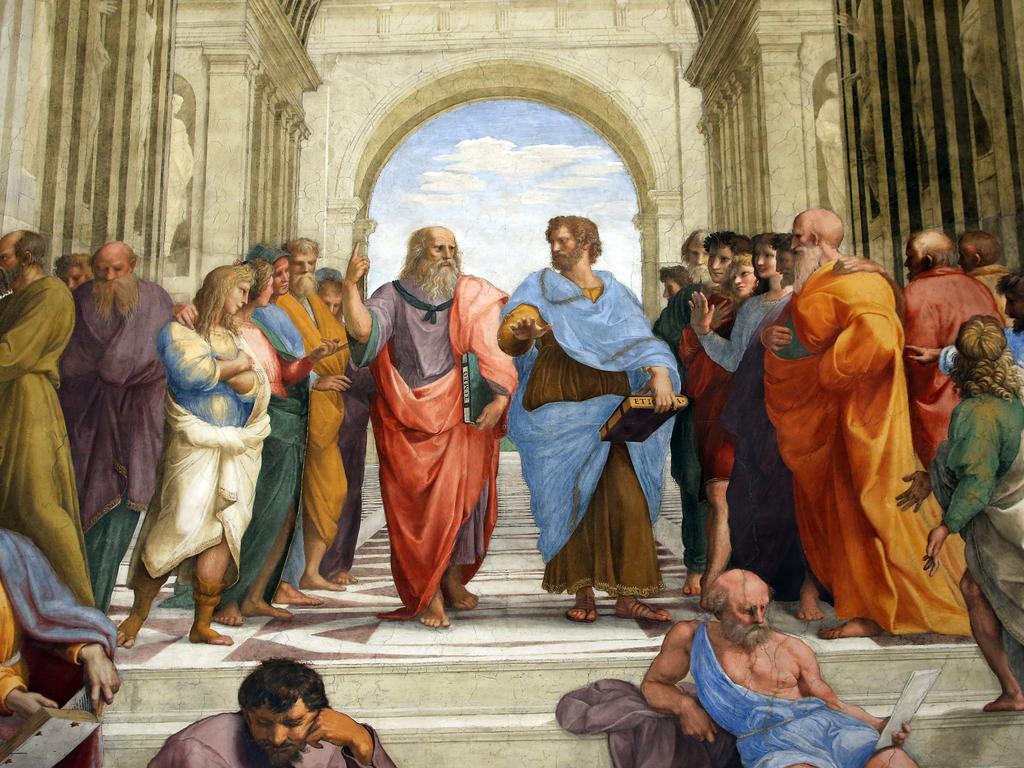

At the school, Allen holds the title of senior master in academic extension, teaching senior students art history and classical Greek and Latin. He regards teaching the language of Homer, Sophocles and Plato – or other languages – as one of the compass points of a well-rounded education. This year, he and his students are reading The Frogs, the comedy by Aristophanes.

“We laugh in Greek,” Allen says. “Even the frogs croak in Greek.”

Writing a weekly column of art criticism is of a piece with Allen’s work as a schoolmaster. He joined The Australian as national art critic in 2008 and has consistently delivered columns distinguished by his learned, opinionated and discursive style.

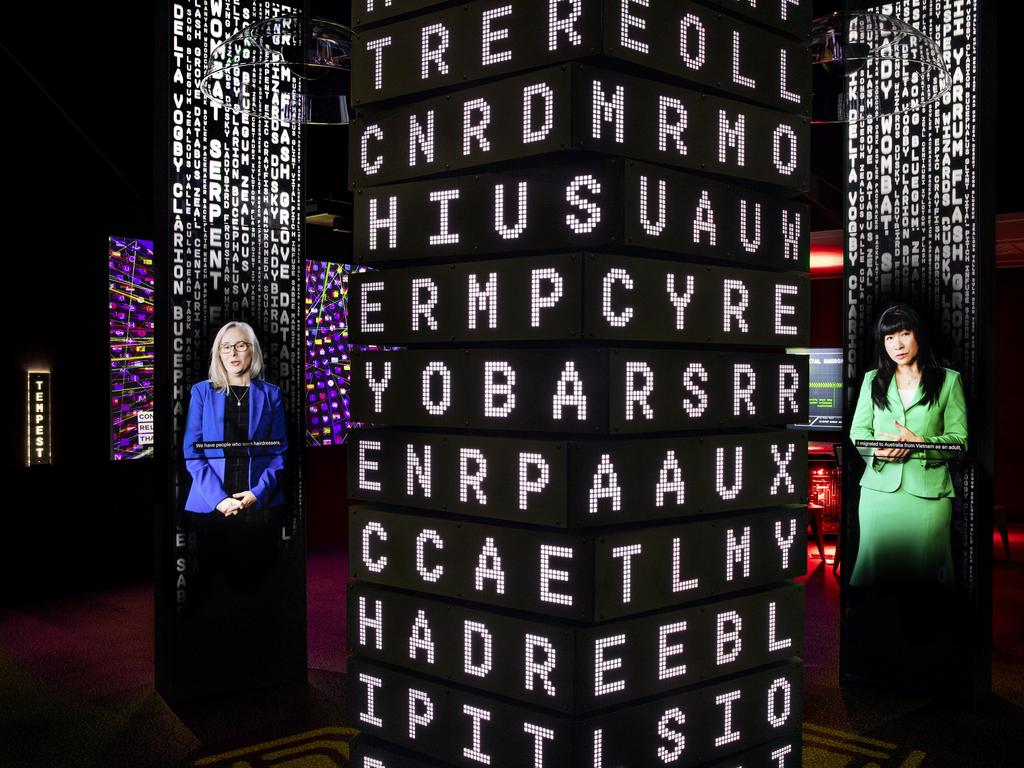

Many Saturday mornings have been enlivened by his enthusiasms and frank appraisals. And his range is remarkable, with recent columns on Renaissance master Raphael, contemporary Australian artist David Noonan, and even an exhibition about the Australian Signals Directorate.

He regards himself as a compulsive teacher who, when having learned something for himself, wants to share his knowledge with others, whether the boys at Sydney Grammar or readers of this newspaper.

“Each article is a new challenge – I put a lot of trouble into choosing the things I write about, so they will be interesting and a bit diverse,” he says. “If I was to write only about contemporary art shows I would probably have stopped long ago. That’s why it’s interesting to have a combination of historical art and contemporary art. I’m not interested in commercial junk, or ideological junk …

“I feel that part of the mandate is to show people that it’s possible to think about things, and that they are allowed to think freely.”

We’re talking in Allen’s classroom in the school’s art building. Along the walls are cabinets stacked with art monographs and exhibition catalogues. A large dictionary rests open on a stand on his desk. There’s a model skeleton and an articulated artist’s mannequin. And on a side table, printout copies of Allen’s art columns from Review.

The purpose of this interview is Allen’s new book, A Companion to Australian Art, a scholarly volume he has edited and written the introduction and conclusion. This new volume comes after his earlier survey, Art in Australia, for Thames & Hudson’s World of Art series in 1997, and his belief that the history of art in this country is often underestimated.

He refers by way of example to the artists of the Heidelberg School – also known, erroneously in Allen’s view, as the Australian impressionists – and their originality when compared with American artists working at the same time.

“I think our artists of the Heidelberg period are far more interesting than the American impressionists,” he says, referring to the group that included Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton. “The American impressionists are tied too closely to the apron strings of the French ones, whereas our impressionists are out here at the ends of the Earth.

“They are facing the distinctly different social and historical circumstances of a country that is just emerging from being a series of colonies and becoming a nation. So, for them, there’s a whole national impetus behind their painting, which isn’t at all in the American impressionists. The American impressionists are just trying to be Monet.”

Even so, as he writes in the new Companion, no Australian artist or group of artists has been so influential that they have had any discernible influence on the direction of world art. We have not produced a Caravaggio or a Pollock, for example, although he points out that few artists at any time in history have made such a lasting impression on the visual culture.

“I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing, I don’t think it means they are not interesting,” he says.

“Nobody in Europe is influenced by von Guerard or Martens – even though von Guerard is a very fine artist, and it’s fantastic the way he has been rediscovered and re-evaluated since the ’80s,” he says. “And painters like Roberts and Streeton are remarkable artists, but they don’t have any influence beyond our shores.”

The Companion has chapters on the art of the colonies, and on the important developments and art forms since then.

Allen has assembled as contributors many respected writers and curators, with essays from Gerard Vaughan on the history of art museums in Australia; Barry Pearce, on the exodus of artists from Australia from the 1880s to the 1930s; Sasha Grishin, on Australian modernism; and Isobel Crombie on photography.

Other writers include Georgina Cole on the Heidelberg School, Mark de Vitis on portraiture in colonial times, and Philip Jones on Aboriginal art.

Allen, 68, has a fascinating personal history that helps explain some of his interests and preoccupations. His paternal grandfather was decorated soldier Arthur Samuel “Tubby” Allen, who served in World War I and helped lead the first Australian deployment to the Middle East in World War II. His portrait by William Dargie is in the Australian War Memorial.

“He fought the Germans and Italians in Egypt, he fought the Germans in Greece, he defeated the Vichy French in Syria,” Allen says. “Then he was brought back to Australia and fought the Japanese on the Kokoda Track. He was a remarkable man. Very sadly, I never met him.”

After the war, the family settled in Cairo, where Christopher’s father, Arthur Robert Allen, learned French. Because he spoke French he was later posted to Algeria, which is where Christopher was born. Later postings sent the family to London, then to Saigon, where Christopher attended a French school, and to Japan, where he regrets he didn’t learn to speak Japanese.

Early in his working life, before he started writing art criticism, Allen taught French at university and was also the inaugural manager at the Performance Space, a venue for experimental art. In his criticism these days Allen can be disdainful of jejune or sloganeering art, but he speaks of his time at the Performance Space with something like nostalgia.

“There was a sense of urgency and edginess – not selling out to the establishment,” he says. “Sometimes it was naively Marxist and a bit silly.”

He remains alert to hypocrisy, superficiality and misjudged priorities. He diagnoses at least two deficiencies in the visual culture of our era whose symptoms are a general disengagement and failure of discernment. First is the decline of common systems of belief – and their associated images, such as in religious art – that were a feature of civilisation before the scientific revolution.

Second, contemporary art that could once have been genuinely provocative and revolutionary has been co-opted by big business in the form of sponsorships, becoming in effect a “corporate accessory”. As he writes in the Companion, certain kinds of contemporary art can exist only in the special zone of contemporary art museums, “excised by a kind of extraterritoriality from the real world of social and economic relations”.

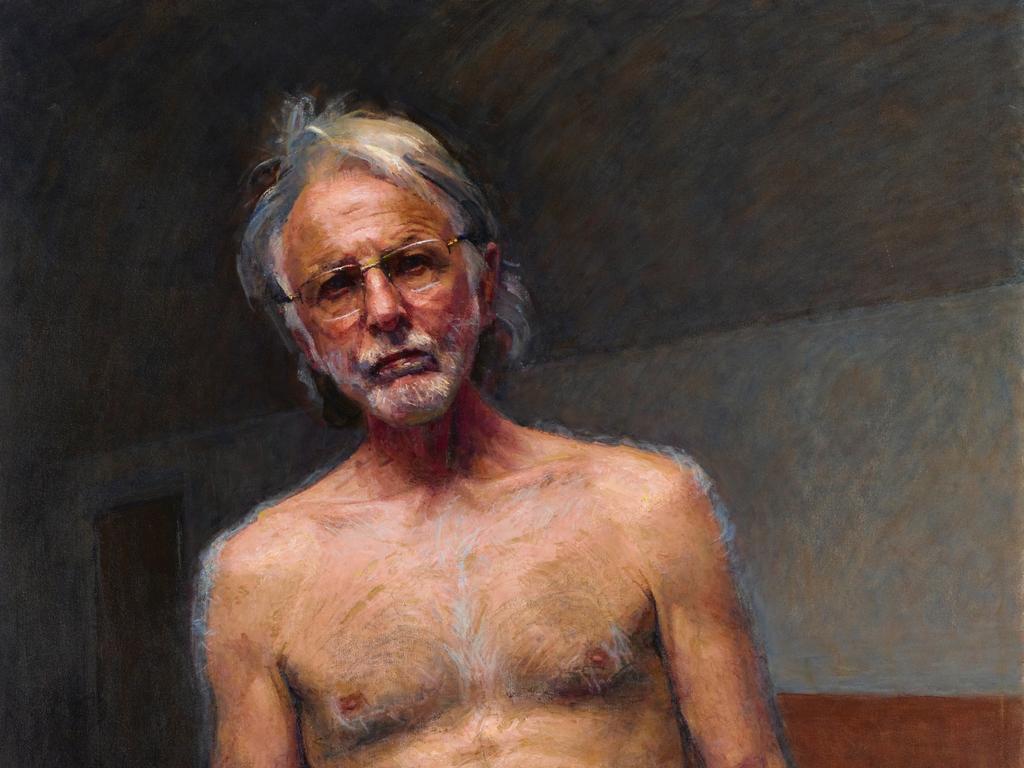

Allen almost shudders when the discussion turns to the Archibald Prize – “My nightmare! No!” – which he finds reason to skewer pretty much every year. His complaint isn’t that artists submit portraits in a wide range of styles, or that the selected works seem to represent a checklist of identity groups – rather that the paintings chosen as finalists by the Art Gallery of NSW generally are of poor quality.

The oversize heads that have been a feature of the prize in recent years are the kind of portrait, Allen contends, that no one would want painted of themselves.

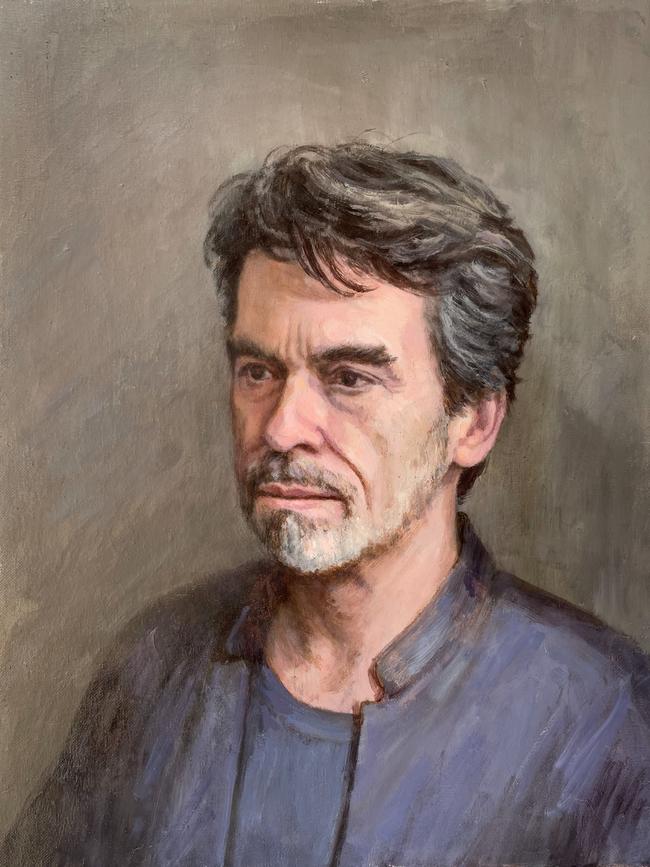

Allen’s artist wife, Michelle Hiscock, painted a small and distinguished likeness of him for the Archibald this year – and who can say on what grounds it was rejected from the lineup. It is hanging in the “alternative Archibald”, the Salon des Refuses, at the SH Ervin Gallery.

In the classroom and in print, Allen carries people along with his knowledge and enthusiasm about art and much else.

“From the point of view of readers, I hope I can share the things I have come to understand,” he says. “One of the things I enjoy is that (each column) is a new creation, and I hope that each time it can offer some sort of enlightenment to people.”

A Companion to Australian Art, edited by Christopher Allen (Wiley-Blackwell, 560pp, $323.95).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout