Raphael formed the backbone of the modern tradition of painting

High Renaissance artist Raphael formed what became the backbone of the modern tradition of painting

There have been a number of important commemorations in the last couple of years, from the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death in 2021 to this year’s centenary of the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, as well as the death of Marcel Proust in November, although the publication of the successive volumes of his great novel A la Recherche du temps perdu continued until 1927.

2019 was the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, and 2020 of the premature death of Raphael, at the age of 37, on Good Friday of 1520. The National Gallery in London had planned an important international exhibition at the time, but like so many other things in the years of Covid, it had to be deferred; fortunately it has been possible to hold the exhibition, even if it later than expected. I will unfortunately not have the opportunity to see it in person, but the occasion is too important to pass without notice and discussion.

In the history of modern art, there is no other individual who has been consistently held in such esteem for so long, and perhaps none whose influence has been so profound and pervasive.

Even when a group of British painters, a century and a half ago, chose to call themselves Pre-Raphaelites, they were less asserting their opposition to Raphael himself than taking him as epitomising the modern tradition of painting that arose in the High Renaissance and expressing their admiration of the earlier painters who were sometimes called the Italian Primitives.

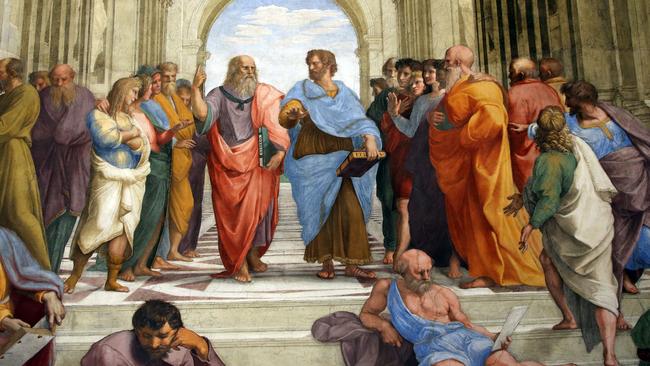

And yet today Raphael is, to the general public, the least familiar of the three giants of the High Renaissance. Every mass tourist in Rome has two sights on their list: the Colosseum and the Sistine Chapel, although they really understand nothing about either. On their trek through the Vatican Museums to the Sistine Chapel, stupefied crowds are capable of walking through the Stanza della Segnatura without the slightest awareness of paintings that are among the greatest ever made; their response to the Sistine ceiling which is their goal would be identical if they had not heard about its fame.

In the age of mass tourism, that is the tourism of the uneducated, a certain number of works of art and places have been labelled “iconic” and people are persuaded that, for some reason, they must set eyes on these “iconic” objects before they die. What endows things with this magical status? Originally, it may have been some insightful or eloquent piece of writing, like Walter Pater’s famous evocation the mystery of the Mona Lisa (1869). Then it becomes a cliche that sustains itself through repetition, so that the Mona Lisa is today the most famous painting in the world even though almost no one in the crowds that go to see it has any idea why it is important or even mysterious.

It helps to be eccentric, excessive or larger-than-life in some way. Leonardo, the astonishingly talented and brilliant genius who is rightly credited with having initiated the period of the High Renaissance, and yet who finished so little, and Michelangelo, so staggeringly gifted in so many different fields, a difficult personality but a giant in every sense, are easier to turn into legends; but in reality it was Raphael, a young prodigy with a gentle and serene personality but an extraordinary ability to understand and assimilate the achievements of others, who learnt from both, pruned the excesses, and formed what became the main backbone of the modern tradition of painting.

It was apparent to critics from quite an early period that although Michelangelo was a stupendous artist, he was not necessarily a good model to emulate, certainly not for beginners, who could be overpowered by forms that they did not yet have the depth of knowledge to understand. That is why so many of the mannerist artists of the 16th century struggled in his shadow; it is not until Annibale Carracci that we encounter an artist whose own foundations are solid enough to learn from Michelangelo without being crushed by his example.

Raphael created a painterly language, especially for representing the human figure, that was solidly grounded in an understanding of human anatomy as well as grand and noble – drawing on the antique as well as Michelangelo and earlier renaissance masters like Masaccio – and, inspired by Leonardo, fluent, expressive and elegant without being emphatic, excessive or histrionic. This was a language that could be taught, that could form the basis of sound and confident style, and that could be developed and reinterpreted for different expressive ends; whereas copying Michelangelo almost always ended up producing a hollow pastiche.

Throughout the early modern period, every artist was trained as the apprentice of an older one, but Raphael’s formulation of a teachable discipline laid the foundations for the academies and art schools that began to emerge a century or more after his death; and his inspiration remains visible in the narrative painting of artists as different as the Carracci, Poussin, the Neoclassical school and even Degas and Picasso.

At the same time his formal understanding of painting as a pattern on the flat surface of the picture plane inspired the compositional inventions of Poussin and through him those of Cézanne.

Raphael was born in 1483 – according to tradition also on Good Friday – in one of the most civilised centres of the 15th century renaissance, Urbino. He was initially taught by his own father, Giovanni Santi, who was court painter, and later by Pietro Perugino, one of the leading masters of the latter part of the 15th century, along with Domenico Ghirlandaio who taught Michelangelo and Andrea Verrocchio who taught Leonardo; all accomplished artists destined to produce far more brilliant pupils.

Although Raphael was born eight years after Michelangelo and was a whole generation younger than Leonardo, his development as an artist was so rapid that – after remarkable early works in the north and then in Florence – he was already in his mid-20s asserting himself as one of the leading painters of his day.

By 1508 he had been commissioned to paint the first of a suite of rooms in Pope Julius II’s private apartments, which meant that for the next few years he and Michelangelo – then painting the Sistine Ceiling (1508-12) – were working at the same time in different parts of the Vatican palace.

The first of the Vatican Stanze, as they are known – the word simply means “rooms” – was Julius’s private library and the four walls represented the four main sections of the collection: Theology, Philosophy, Poetry and Jurisprudence. The division itself speaks of a humanistic vision, placing Theology, the study of divine revelation, theoretically on the same footing as Philosophy, the pursuit of human reason, and taking Poetry or more broadly literature, whose subject is essentially human experience, as seriously as Jurisprudence, which itself encompassed both Civil Law and Canon Law (a crucial distinction not recognised in either the Judaic or Islamic traditions).

The success of these rooms, with their magnificent collection of eloquent and inventive figures, which as many have pointed out became an inexhaustible inspiration to later painters, led to the commission for the second room, the Stanza di Eliodoro, then the third, the Stanza dell’Incendio and finally the fourth, the Sala di Costantino. Julius died in 1513, but the rooms were continued under his successor, the Medici Pope Leo X.

The volume of work that was demanded of the young but extraordinarily energetic artist was such that he had to rely increasingly on a team of assistants, all of whom, as the catalogue rightly reminds us, were of very high ability in themselves and who continued to have successful careers after Raphael’s death. Artists had always had assistants, but they were usually their own apprentices. Raphael in effect created a new model of the modern artist’s studio, which would be replicated by later artists who had to cope with huge demand and large-scale projects, notably Annibale Carracci, Rubens and Bernini. Other artists, it should be noted, like Caravaggio, Poussin or Rembrandt, preferred to work largely on their own, because they concentrated on individual easel pictures rather than undertaking vast public projects.

The collaboration of large teams under a master’s direction was made possible by the painterly language I mentioned earlier; because Raphael’s style was universal rather than idiosyncratic, all members of the studio could learn and conform to it without crushing their own individuality; so that Raphael was able to design all or most of the big painterly schemes, from initial sketches to life studies and finally the preparation of full compositional drawings. His team could be more involved in scaling these drawings up to full-scale cartoons, which he could correct. Then the painting of the large frescoes could be partly executed by him, while other parts could be left to senior members of his team like Giulio Romano.

This kind of process also helps to explain the growing interest of collectors in acquiring drawings, which often represent most closely and intimately the hand and mind of the artist.

Meanwhile Raphael was indefatigable in exploring other media, notably printmaking, in which he recognised the potential to publish his painting and vastly extend the range of its influence. Working with the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi, he produced a number of very important prints, the most famous of which are The Judgement of Paris and his masterpiece of formal invention, The Massacre of the Innocents.

Raphael was also commissioned by Pope Leo to design a sumptuous and enormously expensive set of tapestries, devoted to subjects from the Acts of the Apostles, to complete the decoration of the Sistine Chapel. They cannot be displayed there when the chapel is filled with tourists, but they were rehung for a time in 2020, and the photographs in the catalogue show how impressive they look, hanging under the first set of frescoes painted in the chapel in 1481-82. The tapestries were woven in Flanders, but fortunately seven of the 10 full-scale cartoons survive and are among the greatest masterpieces of High Renaissance art (London, V&A), embodying some of Raphael’s most sophisticated compositional ideas.

All of these projects were extremely demanding and, as already noted, would have been impossible without a highly-organised team of expert assistants. But it is notable that, like Rubens after him, Raphael always reserved certain commissions, and in particular portraits, for his own execution. And one consequence of this is that although no museum outside Rome can include the great frescoes in the Vatican, the National Gallery exhibition can include some of the paintings that most intimately embody Raphael’s supreme mastery and subtlety in the art of painting, like the exquisite, almost monochrome portrait of his friend Baldassare Castiglione, the quintessence of the gentle and civilised face of renaissance humanism.

Raphael, The National Gallery, London, until July 31.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout