Bloody eccentricity and ancient history: Machu Picchu exhibition has it all

You’re much more likely to find violent human sacrifice than ‘healing’ in the early cultures of the Aztecs and the Incas.

The greatest civilisations of humanity – today increasingly merged into the amorphous world of the globalised consumer society – began from three epicentres, in the Fertile Crescent, the Indus Valley and the Yellow River valley. They all developed from around 10,000 years ago with the Neolithic Revolution, the discovery of agriculture and specifically the cultivation of cereal crops which allowed larger populations to live together in cities rather than remaining isolated in the small tribal or even family groups of hunters and gatherers.

In the age of agriculture, as mentioned last week, a part of the population could be occupied with growing staple crops, while some specialised in building, the manufacture of tools, clothing and utensils, and others became responsible for administration and defence. New crafts arose, from ceramics to metallurgy; around 5000 years ago the wheel was invented (the cart wheel, but also the potter’s wheel); writing appeared in the same period, at first just for records but gradually revolutionising the human mind. For the first time knowledge could be set down in objective form; it became possible to think about knowledge instead of simply memorising it.

In other words, the invention of writing made critical thinking, reflection, speculation and theorisation possible for the first time; and so it is not surprising that philosophy and scientific thinking, as well as theology and higher religions, all begin to appear around the middle of the first millennium BC, or a little earlier in some places. Homer, in the 8th century, is on the cusp of poetry and proto-philosophy, critical thinking appears with pre-Socratic philosophers from the 7th and especially the 6th centuries, at roughly the same time as Zoroaster in Persia, Buddha in India, Confucius and Lao Tsu in China.

In Central and South America, however, we have the only other example of a civilisation, or rather a cluster of civilisations, arising autonomously and without the benefit of external influence, although unlike the great Eurasian civilisations, which have gradually spread to the whole world, the pre-Columbian ones were largely extinguished by the Spanish conquests and survive only in vestigial form and within the folk culture of their original homelands.

There is no doubt about the impressive achievements of these peoples, especially in one of the most conspicuous signs of any civilisation, ambitious monumental architecture. They were nonetheless limited and even defective in several important respects. Perhaps the most obvious of these is that they never entered the Iron Age; and even though some of them made bronze, metallurgy in general seems to have had mostly ritual, ceremonial and ornamental functions rather than practical applications.

Pre-Columbian civilisations also developed various systems of writing or proto-writing – the only case of the spontaneous emergence of such systems outside Eurasia – of which the most sophisticated was the Mayan script. But these systems seem to have been made up of visual symbols as much as signs corresponding to spoken language, and they seem to have been largely used for astronomical and religious records and political chronicles. Consequently these cultures never developed historical or critical thinking or higher religion; indeed the most salient characteristic of pre-Columbian civilisations is that they retain, alongside their technical sophistication, religious customs that can only be called primitive and even savage.

This makes it all the more surprising to find that so many people today appear to have completely misunderstood the culture represented by Machu Picchu and Andean traditions more generally, the subject of the present exhibition. On a typical web page advertising tours to Machu Picchu and appealing to the whole mish-mash of new age beliefs in crystals and “energy”, the place is described as a “sanctuary of spiritual awakening” and “a place of healing energies, deep connection to nature, and reverence for Inca spirituality”. Presumably these seekers after “healing”, that most nebulous of new-age notions, are not aware that “Inca spirituality” involved regular human sacrifice to appease furious and violent deities.

The Australian Museum exhibition, though relatively compact, offers an effective and impressive introduction to what is clearly a remarkably beautiful place and, as already suggested, a particularly alien culture. In fact while part of the exhibition is specifically devoted to the site and structures of Machu Picchu, the more general focus is on Andean culture across a number of centuries and several different peoples and periods, mainly within the millennium or so preceding the Spanish conquest.

Thus although the exhibition largely deals with themes common to Andean cultures over the centuries, much of the work belongs to the Moche culture, which flourished from around 100-800AD. The Incas themselves appeared much later, around the 13th century, and Machu Picchu was built towards the end of their history, in the 15th century, not long before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. The city itself, situated in a remote mountainous location, remained unknown to the Spanish and gradually disappeared into the jungle, forgotten by all but some local tribes, until it was rediscovered in 1911 by the American archaeologist Hiram Bingham.

The exhibition begins by introducing us to the world of Andean cosmology which, as in most cultures, is built around a strong polarisation of male and female and distinguishes three main levels of existence: a heavenly realm inhabited by gods, the earthly realm of humans and an infernal or chthonian world inhabited by the dead and demons, but which is also crucially involved in the renewal of life. Like other cultures again, they associate these realms with non-human creatures, particularly birds for the air and snakes for the underworld.

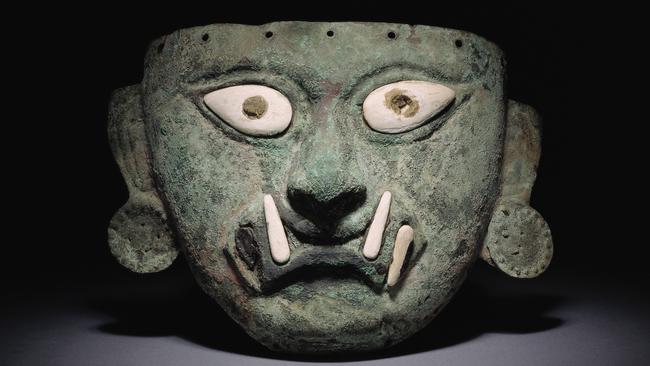

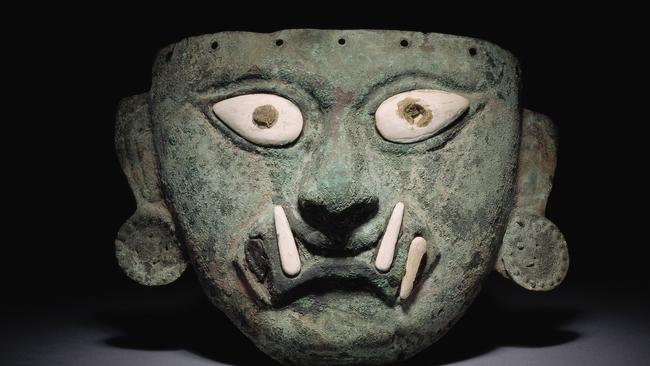

But the Andeans were closer to primitive cultures in seeing a close and almost totemic identification between the divine, animals and humans. Leaders and rulers, in particular, were thought to have a shamanic affinity with the animals that signified these realms, including birds and snakes, but especially feral cats in the earthly world, so rulers are often represented with a panther’s fangs. These men, considered as in some respects divine beings, also have the ability to take on various other animal forms as they move through the dimensions of life.

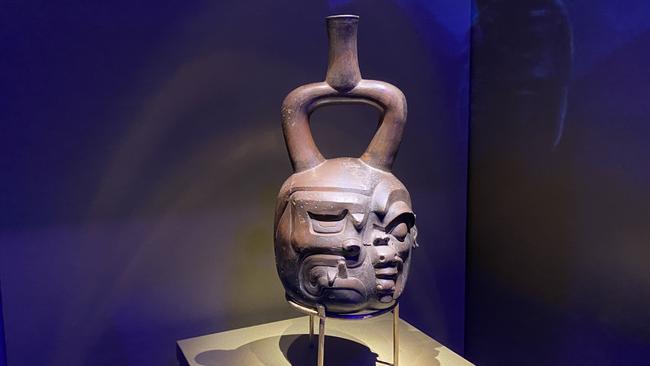

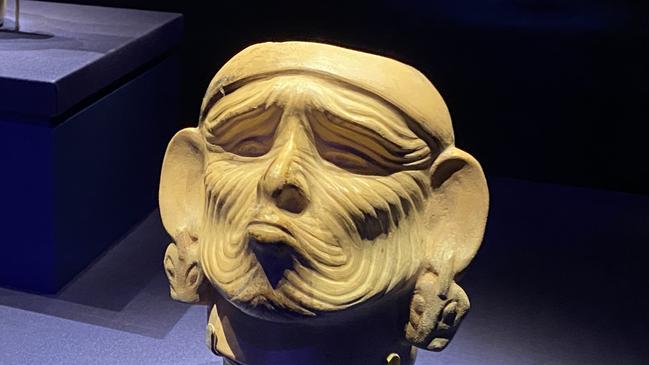

And this leads us to the first main part of the exhibition – after the introductory room – which tells of the mythical quest of the culture hero Ai Apaec. Alarmed to see the sun setting into the ocean and fearing it may never return, he determines to pursue it and set it free. He has a series of adventures, illustrated in paintings on the walls for the benefit of children, but also by a collection of remarkable ceramic wares, which show him gradually assuming various animal forms as he overcomes a monstrous crab, blowfish, sea-urchin and other antagonists. Just as Ai Apaec is inherently a figure of the primitive mythic mind, far from the fully human quest-heroes of Greek myth such as Jason, Perseus, Heracles or Theseus, he is also drawn into endless metamorphic transformations in his struggle with his animal adversaries.

The enduring popularity of this myth is attested by many works from centuries apart, including as already mentioned several ceramic vessels that represent him in his different guises, but also a particularly fine wide-mouthed dish with highly refined and graphic images of Ai Apaec and some of the main episodes of his quest decorating its rim.

The next section of the exhibition deals with the ritual of human sacrifice. In other advanced civilisations, the idea of human sacrifice may exist, but it is always associated with remote times or barbaric peoples; Agamemnon, for example, agreed to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia at the demand of Artemis, but in the end the goddess mystically substituted a deer for the girl, whom she took away to be her priestess in Tauris (Crimea) – where, in a remote barbaric land, she presided unwillingly over a cult of human sacrifice until she was rescued by her brother Orestes.

In pre-Columbian civilisations, however, human sacrifice remained endemic. It was perhaps even more extreme among the Aztecs, but in Inca culture it seems to have been preceded by a duel between two aristocratic warriors, each of whom knew he would die if vanquished, yet apparently considered even this death to be glorious, since he would be giving his life to appease the terrifying gods they dreaded. After being wounded or being seized by the hair by his opponent, the loser would be stripped naked, consecrated to the gods and then taken to the temple where the priest would ceremonially cut his throat and tear out his heart. And thus the gods, their anger temporarily assuaged, would allow the rains to continue to fall and the crops to grow on the terraced hillsides of mountain cities like Machu Picchu.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to the burial finery of the rulers, including a great deal of gold, since the modern museum-goer seems to be as eager for gold as any of the Spanish conquistadors. In fact the word “gold” is almost compulsory in any archaeological exhibition that is intended to have mass appeal – just think of the title of the Australian Museum’s Egyptian exhibition earlier this year: Ramses and the Gold of the Pharaohs.

Metallurgy, as mentioned before, was largely confined to ritual and ceremonial purposes in the Americas, and gold in particular, as almost everywhere in the world, was the most valued and precious metal, for being not only rare and beautiful, but also imperishable and untarnishable. It was the natural symbol of immortality, and thus used in the burials of monarchs and princes, especially when, as in these cultures, rulers were considered to share in the attributes of divinity.

It is in fact a decade since the Australian Museum presented an exhibition of Aztec culture, reviewed here on Saturday, 8 November, 2014. On that occasion I quoted the remarks of Georges Bataille from an essay written in 1928, at the height of Surrealist interest in tribal cultures: “The life of civilised peoples in pre-Columbian America is a source of wonder to us, not only in its discovery and instantaneous disappearance, but also because of its bloody eccentricity, surely the most extreme ever conceived by an aberrant mind. Continuous crime committed in broad daylight for the mere satisfaction of deified nightmares, terrifying phantasms, priests’ cannibalistic meals, ceremonial corpses, and streams of blood …”

This should certainly be compulsory reading for the people who imagine Inca spirituality to be all about “healing”, but it could be worse. At least in Incan culture sacrifice resulted from a voluntary combat between two heroes; among the Aztecs, the main purpose of war was to secure captives to be slaughtered in the most horrific and violent manner imaginable. But on the whole it is probably safe to conclude that spiritual enlightenment is more likely to be found in the religions and philosophies of India than in those of Central and South America.

Machu Picchu and the Golden Empires of Peru, Australian Museum, Sydney, until May 11.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout