Aztec: Conquest and Glory at Australian Museum explores art of darkness

THE Aztec exhibition at the Australian Museum sheds light on a society steeped in blood, and in which human sacrifice was a daily occurrence.

GEORGES Bataille (1897-1962) was a philosopher, anthropologist, archivist and numismatist, perhaps best known for his Histoire de l’oeil (Story of the Eye) (1928), a sort of epic of erotic excess in the direct filiation of the Marquis de Sade. As a lover of the transgressive and as an anthropologist, he also wrote a thought-provoking essay on the Aztecs, published in the same year, at the height of surrealist interest in tribal culture and its more extreme manifestations.

The essay, whose insight derives from a unique combination of sympathy and horror, was published in English translation in 1986 as Extinct America in the art-theoretical journal October, and subsequently reprinted in the anthology October: The First Decade (1987). As Bataille writes in the opening of the piece: “The life of civilised peoples in pre-Columbian America is a source of wonder to us, not only in its discovery and instantaneous disappearance, but also because of its bloody eccentricity, surely the most extreme ever conceived by an aberrant mind. Continuous crime committed in broad daylight for the mere satisfaction of deified nightmares, terrifying phantasms, priests’ cannibalistic meals, ceremonial corpses, and streams of blood …”

As the author goes on to say, this applies above all to Mexico, though the case of Peru also confronts us with the paradox of a society that meets the basic criteria of civilisation — the mastery of agriculture and the construction of cities — yet exhibits the signs of a retarded moral development and religious practices more akin to those of tribal animists.

Now, with the impressive Aztec exhibition at the Australian Museum, we have the opportunity to ponder a society even more steeped in blood, and in which human sacrifice was a daily occurrence. The exhibition comes from several institutions in Mexico and includes many important finds that have been excavated in Mexico City and restored only in recent decades.

Like the Incas, the Aztecs were fairly recent conquerors, but similarly inherited and carried on already longstanding traditions. Their culture had twin foundations in agriculture and warfare, and this was reflected in the double patronage of the Great Temple in their capital Tenochtitlan, today the site of Mexico City.

The temple, which grew higher in the course of seven rebuildings by emperors seeking to outdo their predecessors, was dedicated to Tlaloc, god of rain and fertility, and to Huitzilopochtli, god of war. Each of these divinities required a constant supply of human sacrifices, which could range from young girls to captured warriors. Indeed the principal object of war, apart from territorial expansion, was to capture prisoners for sacrifice.

For this reason all boys, aristocratic and commoners, underwent military training, using wooden clubs and spears tipped with flint, for they had no iron; they were essentially an advanced Neolithic culture that had discovered gold and silver, and some copper, for ornamental purposes but not the smelting of harder metals.

Once captured, prisoners dedicated to the gods were initially treated with some consideration because, like all sacrificial offerings, they were sacred. But when they were killed, it was in a spectacularly horrible manner.

The victim was stretched backwards over an altar, a temple assistant holding each limb, as we see in drawings done by Aztec artists immediately after the Spanish conquest. Then the priest slit open their abdomen with a flint blade, reached into the cavity and tore out their heart. The corpse was then thrown down the steep stairway leading to the top of the temple; later his body would be eaten by the priests.

In the most gruesome variant, used in the cult of the spring god Xipe Totec, the priest would flay the victim and put on the bloody skin, which would cover his body and head. He would wear this skin for 20 days until it rotted and fell away like that of a moulting snake — this being the symbolic reference in a cult of seasonal renewal.

We see the priest wearing the victim’s skin, with hands and feet flapping at wrists and ankles, once again in drawings made by Aztec artists in the Florentine Codex (c. 1577), among the most important sources of information of Aztec culture before the surprisingly rapid disappearance to which Bataille alluded.

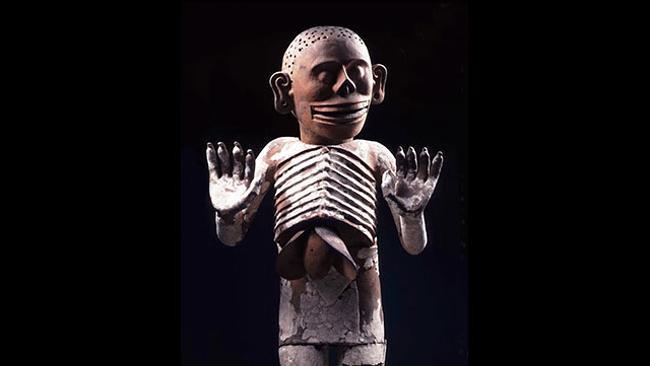

Even more bizarre are earlier, pre-contact sculptures of figures that seem almost incomprehensible, for they appear to have wide gaping mouths and two sets of lips, as well as a horizontal slit in the chest like a letterbox. Without documentary evidence, we would never guess, or believe, the truth: that they represent the priest wearing the skin of the sacrificed man, the flayed lips stretched wide around the real mouth of the priest himself. The slit is where the heart has been extracted.

It is hard to imagine the full reality of such practices: not just the brutality of the killing — the screaming, the blood, the cries or cheers of the onlookers — and the anthropophagic feasting that followed, but the nauseating stench of the decomposing skin. It must have been unbearable to anyone who came close, and for the priest himself the ordeal must have reached almost hallucinatory proportions.

Yet these daily horrors coexisted with the working routine of a prosperous and efficient city, built on islands of reclaimed land in the shallow water; here, the peasants grew vegetables of all sorts, while the lake yielded fish and water-fowl. They lived in simple windowless huts and were restricted to wearing rudimentary clothing — cotton was reserved for the nobility — but they were presumably relatively healthy and well-fed.

Cortes arrived in 1519, a year in which it is said — though this has been questioned by some historians — the Aztecs were expecting the return of the exiled god Quetzalcoatl, who was predicted to liberate the people they had subjugated. For this reason, they may have taken Cortes and his men for gods — so unexpected in appearance in their steel armour, and mounted on horses — and have been anxious to placate them.

Cortes presumably knew nothing of this at first, but did seek alliances among the subject people, and especially among the Tlaxcaltecas, a neighbouring people who had never been conquered by the Aztecs. By the end of 1519, he had reached Tenochtitlan, taken the emperor Moctezuma hostage, and made him accept to be a vassal of the Spanish empire.

But things became more difficult once Cortes started trying to impose the Catholic faith, remove idols and abolish the all-important human sacrifices. The priests fomented revolt, and violence broke out while Cortes was away in early 1520 dealing with a force sent by the governor of Cuba to arrest him for exceeding his mandate.

Cortes made concessions in an attempt to restore peace, including releasing Moctezuma’s brother, and having Moctezuma appeal to the people to stop the fighting, but according to Spanish accounts, the emperor was killed by his own angry people. On July 1, 1520, in what was called La Noche Triste — the sad night — the Spanish fought their way out of the city in revolt, losing about half their men in the process.

They retired to Tlaxcala to regroup and plan the retaking of Tenochtitlan, including building ships for a waterborne assault, as the city was constructed in the middle of a lake. In the meantime, an African slave infected with smallpox is said to have brought this unknown and devastating disease to Mexico; it reached the capital by October and by December had spread through the population with dreadful consequences.

In May 1521 the assault began, although it was not until August that the city finally fell. More than 100,000 Aztecs, perhaps half the city’s population, had died, either from fighting or from disease and hunger.

The process of hispanisation and Christianisation began at once and was rapid, no doubt because the people were utterly disillusioned at the powerlessness of their gods to defend them, and shocked to discover the sun rose, rain fell and crops grew even after the cessation of the bloody sacrifices they had so long believed vital to their survival.

The most striking aspect of this exhibition is the ubiquity of images of death — grim, oppressive, but at times almost comical, as Bataille insightfully suggested, and above all grotesque. No figure better epitomises this bizarre mixture than the standing Mictlantecuhtli, greeting new arrivals in the land of the dead with open arms, terrifying claws, clown-like grin and disembowelled organs.

What is significant is what is absent. There are no figures of joyful sensuality, none of the celebrations of energy, movement and fecundity we find, for example, in Indian sculpture. There too, as in most religions, there is a connection between death and regeneration, but instead of relentless images of mortality, we find the ecstatic dance of Shiva, embodying the endless cycle of change.

There are, in fact, no images of human beauty. One would not expect the fully developed conception of the ideal body that was developed by the Greeks and that stands as the symbol of confidence in human reason, in individual and social harmony. But neither is there the sense of the dignity and beauty of gods and divinised monarchs that one encounters in Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Still less is there anything like the stillness of Buddhist art, conveying the quietness of the mind that has recognised the illusory nature of desire and fear.

The Aztecs, from this point of view, lived in a maelstrom of such passions, in thrall to evil and bloodthirsty demons. They had a complicated and sophisticated calendar system — used to determine the cycles of sacrifice — but no tradition of wisdom or spiritual practice that could offer an escape from the darkness.

Aztecs: Conquest and Glory

Australian Museum, Sydney, to February 1