Ingredients of a master potter

Josiah Wedgwood was driven by enormous entrepreneurial energy and a desire to experiment, as shown in an Adelaide exhibition.

Renaissance artists avidly studied the remains of ancient art that were available to them, and from Masaccio to Michelangelo borrowed from antiquity to create some of their most memorable works, but the systematic study and especially publication of these works begins in the 17th century. François Perrier’s Segmenta nobiliorum signorum (1638) and Icones et segmenta (1645) were collections of etched plates (100 and 55 respectively) of important antiquities held in Roman collections that were reprinted several times and served as reference books for many artists, especially those who did not themselves visit Rome, such as Rembrandt.

There were many other antiquarian publications in the 17th century, although we often think of modern archaeology as starting in the mid-18th century, with the writings of Winckelmann and the discovery of the sites of Pompeii and shortly afterwards of Paestum. Coinciding with excavations at Pompeii, the declining power of the Ottoman Empire made it possible to visit Greece again; James Stuart and Nicolas Revett were there in the 1750s and published their Antiquities of Athens in several volumes, starting in 1762 and ending in 1816, the year that Britain acquired the Parthenon friezes.

At the same time, Sir William Hamilton – whose second wife Emma became Lord Nelson’s mistress – published in 1766-67 the first of four volumes of works in his own collection; the plates in these volumes, like those of Stuart and Revett, became sources for Greek Revival and neoclassical design, including for Josiah Wedgwood, the subject of an exhibition at the David Roche House Museum which also includes a survey of his firm’s production up to the present day.

Much of Hamilton’s collection was made up of Ancient Greek vases, and it was from this time that the designs on these vases, now so familiar, began to be well-known and to influence contemporary art and design. Oddly, however, it was not at first understood that the best of them came from Attica; because so many were excavated from Etruscan burials, sometimes even by Hamilton himself, it was at first assumed that they were original Etruscan productions: hence the name “Etruria” that Wedgwood gave to his new pottery works opened in 1769.

The modern understanding of Greek ceramics, including both the repertoire of forms and their painted decorations, evolved throughout the 19th century and culminated in the work of Sir John Beazley and a little later the Australian, Arthur Dale Trendall.

The increasing prestige of ancient ceramics was clearly an influence on the young Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95), and perhaps helps explain why he always worked in fine stoneware, rather than porcelain, which Europe had long imported from China before finally discovering how to produce it in the first half of the 18th century.

He was a remarkable individual, born into a family of potters, but driven by a constant desire to experiment and develop new techniques, as well as by the enormous entrepreneurial energy which led him to embrace innovative forms of industrial production and even marketing: the exhibition includes a print of his vast and impressive showroom in St James’ Square in 1809, a decade and a half after his death.

He was also, like many members of Britain’s entrepreneurial class at the time, a Dissenter or Nonconformist, that is a Protestant who did not recognise the primacy of the Church of England.

Until 1828, Dissenters were excluded from election to parliament, employment in government offices, study at Oxford and Cambridge, and holding an officer’s commission in the army. They were hardworking and pious, and leaders of the anti-slavery abolitionist movement, of which Wedgwood was a supporter. In Australian history, they played an important role in the foundation of Adelaide as a free city. And despite their exclusion from the universities, Dissenters were well-represented among scientists and intellectuals; Wedgwood himself, elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1783, was the grandfather of Charles Darwin.

One of his most famous works, and the one that greets us at the start of the exhibition, is his ceramic copy of the Portland Vase, executed around 1790 – displayed with a contemporary ticket for admission to an exhibition of his reproduction in Greek St, Soho. The original vase, once the property of the Barberini family, had been acquired by Hamilton who sold it the Duchess of Portland around 1783-4; today it is in the British Museum.

The Portland Vase is a glass cameo work from the time of Augustus, probably the first decade or two of the Christian era. A normal cameo is made by carving a two-layered piece of a semiprecious stone such as agate, so that a lighter layer becomes the figure on the ground of the darker layer beneath. A glass cameo – a technique developed in the Roman period – is made by producing a vessel, as in this case, with a dark translucent inner layer and a white opaque outer layer, which is then carved to produce sculpted figures set against the dark background.

It is extremely skilled and difficult work, and the resulting piece is very fragile, compared to a stone cameo. Indeed the Portland Vase was shattered by a vandal in 1845, and after many attempts to repair it, was almost miraculously restored in 1988-89.

But the reason that Wedgwood went to so much trouble to copy the vase is that such ancient cameo works, as well as engraved gems from the ancient world, were once held in much higher esteem than we seem to have for them today, perhaps because, then, they were appreciated by connoisseurs and they are not easy to display to the mass public of modern museums.

Anyone who has been to Florence will have visited Palazzo Medici, and perhaps noticed large sculpted roundels in the courtyard; these are reproductions by Donatello’s pupil Bertoldo of some of the famous ancient gems in the Medici collection, which would only be personally shown to special guests. One of these represents Athena and Poseidon arguing over the patronage of Athens, and is reproduced in this exhibition as an ornament on a Louis XVI mantelpiece clock.

So it is no doubt the prestige of the cameo form explains why Wedgwood, though inspired by antique vases, did not attempt to reproduce Attic black or red-figure wares, even if he did borrow some physical attitudes from such sources, through their publication in Hamilton’s books.

Instead, Wedgwood’s most famous and undoubtedly very expensive presentation pieces were, as we see in the exhibition, vessels in the form of classical urns with cameo-like relief decorations.

These works were also the result of Wedgwood’s tireless research and experimentation, to create the appropriate clay bodies as well as to make the figural cameo reliefs. The most common clay body was what he called jasperware, and it could be coloured in his distinctive blue, or sage-green or even black. Originally the whole clay body was coloured in this way, but later the colour was added as a slip.

The white figures were produced in a mould and added to the body before firing; this process is called “sprigging” and the added figures are “sprigs”.

One example of this work from the Wedgwood firm, just a few years after Josiah’s death, is the Virgil vase (c.1800), in black jasper dip stoneware with white figures in cameo relief; in the central motif, Virgil is seen standing, holding a scroll, flanked by two seated Muses – no doubt of lyric and epic poetry – and two figures bringing crowns of laurel.

In the Hercules vase of the same period, the hero is seated against a light blue jasper background, contemplating a pretty girl who holds a cup identifying her as Hebe, the cupbearer of the gods and his future bride. We know thus that the scene represents the hero after his death and apotheosis, about to begin his life as an immortal.

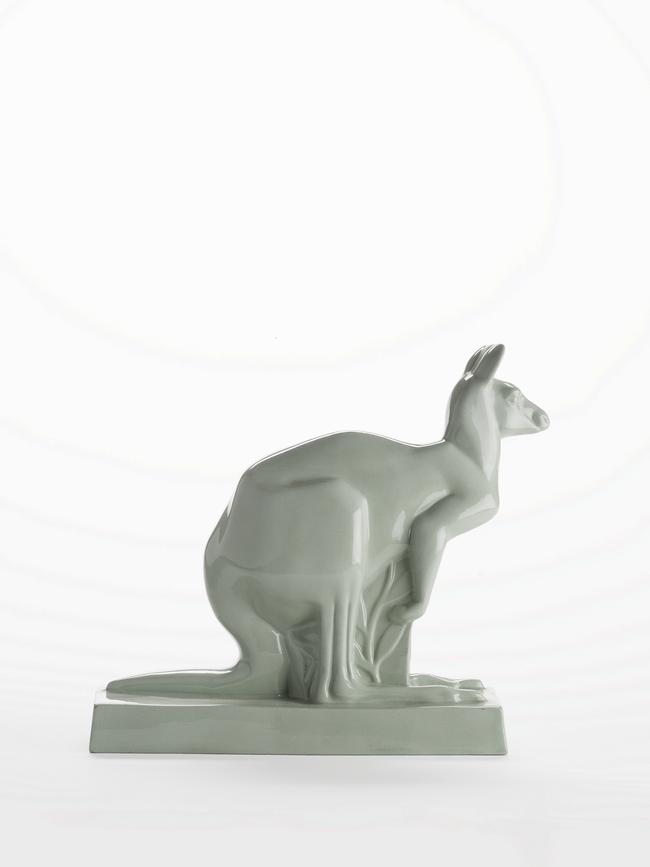

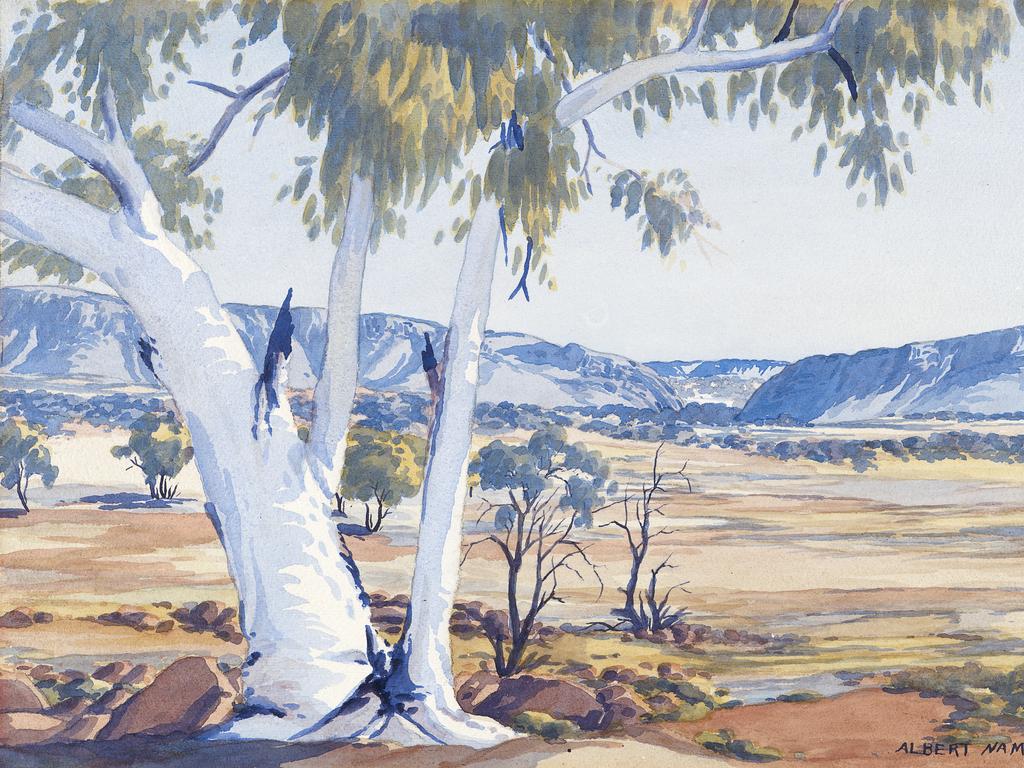

There are several interesting connections with Australia gathered in a cabinet near the beginning of the exhibition, including portraits of Cook (1777), Banks and Solander (both 1920s), and a later production series inspired by Australian flora.

But the most remarkable objects by far are several examples of the Sydney Cove Medallion, which can reasonably claim to represent the beginning of Australian ceramics, since this fundamental technology had, of course, never been developed on the continent before settlement.

Soon after the arrival of the first fleet, white clay was discovered in Sydney Cove which appeared to have the potential to be used for potting. In May 1789 samples were sent back to Sir Joseph Banks, who passed them on to Wedgwood, his colleague at the Royal Society.

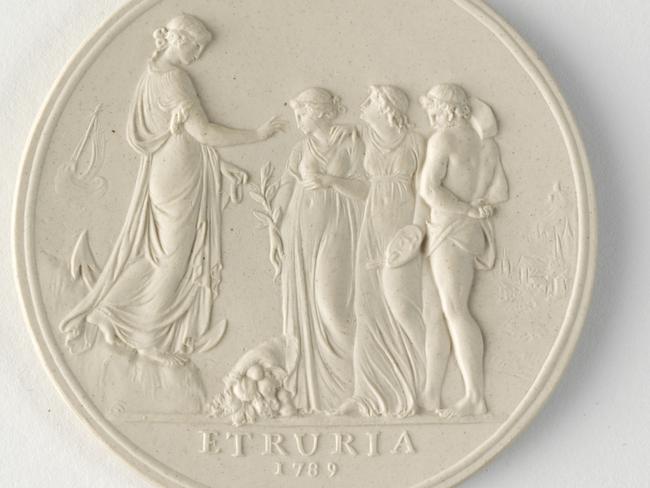

Wedgwood found the clay to be perfectly suitable, and proceeded to make a series of allegorical medallions which became known as the Sydney Cove Medallion, and are here represented in three different colours, a natural off-white, and two different shades of dark brown and black.

The subject of the medallion is “Hope encouraging Art and Labour, under the influence of Peace, to pursue the employments necessary to give security and happiness to an infant settlement”; Hope, with an anchor as her attribute, is seen standing a little above the others, who are, from left to right, a female personification of Peace, holding an olive branch, a female personification of Art, holding a painter’s palette, and a male personification of Labour, holding a hammer like one of the smiths in paintings of the forge of Vulcan.

Between Hope and the other figures lies a cornucopia, suggesting the prosperity of the new settlement. On the back the inscription states that it was made by Josiah Wedgwood “of clay from Sydney Cove”.

The name “Etruria” which appears prominently under the figures presumably refers to Wedgwood’s workshop, already mentioned, but also probably inspired the motto of the colony of NSW, on its Great Seal approved by King George III in 1790: “sic fortis Etruria crevit” (Virgil, Georgics 2.533), meaning “thus Etruria grew strong” and referring to the potential of the state to develop through the labour and industry of the settlers.

It was significantly accompanied by an allegorical image of convicts removing their shackles on arriving in Sydney and being received by the figure of Industry who encourages them to work and transform the new land. This seal was in official use until 1817 (Sydney Morning Herald, May 3, 1941, Page 11).

The Virgilian motto still appears on the NSW coat of arms on the GPO building, carved in 1887.

By then, however, it seems to have been associated with the convict origins explicitly evoked on the original seal, and was apparently already giving way to the current motto “orta recens quam pura nites”, newly risen, how brightly you shine, which was officially adopted in 1906.

Curiously, Virgil’s words survived in adapted form as the motto of Hobart: “sic fortis Hobartia crevit”.

Wedgwood: Master Potter of the Universe. David Roche House Museum, Adelaide. Until January 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout