Biennale of Sydney: The contemporary art of survival

Sydney Biennale has had a chequered history, but half a century after its first iteration a new book about the event reminds us of its champions, its humble beginnings, and why the timing was just right.

You could argue that the Biennale of Sydney would never have happened without Gough Whitlam’s nation-building expansion of the Australia Council in the early 1970s, which added art form boards. Or have survived without the Visual Arts Board’s first head, Leon Paroissien, who helped steer it to sustenance through its most vulnerable early days. Or without Tom McCullough, who not only salvaged the Biennale’s fortunes (as artistic director) in 1976, but helped invent its model. Or his successor, Nick Waterlow, who secured the Biennale’s fortunes at a critical moment, and went on to direct another three key editions. Or the generations of executives, staff and boards who’ve worked similar miracles since.

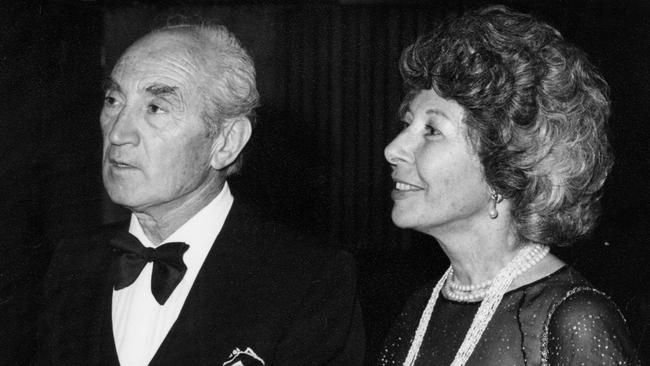

Without question, however, the Biennale of Sydney would neither have happened nor survived without the singular figure ofthe co-founder of engineering, infrastructure and services company Transfield, Franco Belgiorno-Nettis: his imagination, dissatisfaction, opportunism and dogged persistence.

In the lead-up to its first edition in 1973, Belgiorno-Nettis was canvassing widely. Fellow emigre John Kaldor was already a fledgling impresario at the time, responsible for contemporary art’s single defining moment in Australia, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s 1969 wrapping of Little Bay – Wrapped Coast – a seminal event that Transfield had literally helped engineer.

“Franco and I were both very conscious of the lack of international contemporary art,” Kaldor recalls of their conversations at the time. “Australia and the Australian public just weren’t conscious of it.”

“We talked a lot about the need for a biennale, and how important it would be for Australia. Franco being Italian, the Venice Biennale was a very logical reference, but I was also toying with the idea of trying to do something like a biennale. You have to understand there were only two at that time, Venice and Sao Paulo. Now every town with a traffic light has one. Anyway, we talked a lot, but he made it happen.”

A platform for contemporary art in Sydney was in fact an idea of its time, part of a prevailing hunger for change. Whitlam had swept to power in December 1972 after 23 years of conservative rule. “The excitement of that election is hard to imagine now,” says former arts journalist Sandra McGrath, who would chronicle the Biennale into the next decade before returning to the US. “I remember Brett Whiteley and I driving through town in his Jeep with three of his funny-looking dogs and the music blaring, shouting and screaming and hitting the horn.”

McGrath recalls the 70s as “a golden age of Australian art in Sydney and Melbourne. Everything was exploding culturally and politically. The era of Menzies and Dobell and Drysdale was finally over. Sydney was shedding its old colonial-backwater shell, as the Opera House was revealing new ones”.

Indeed, you could argue that 1973 was the year Australia became modern. The incoming Whitlam government officially ended the White Australia policy and cut tariffs, among the highest in the world at the time, by 25 per cent. The Sydney Opera House – mandated 20 years earlier by NSW premier Joe Cahill to “help mould a better, more enlightened community”, as he surveyed a young immigrant nation – finally emerged from the kind of convulsions that would soon wrack the Biennale.

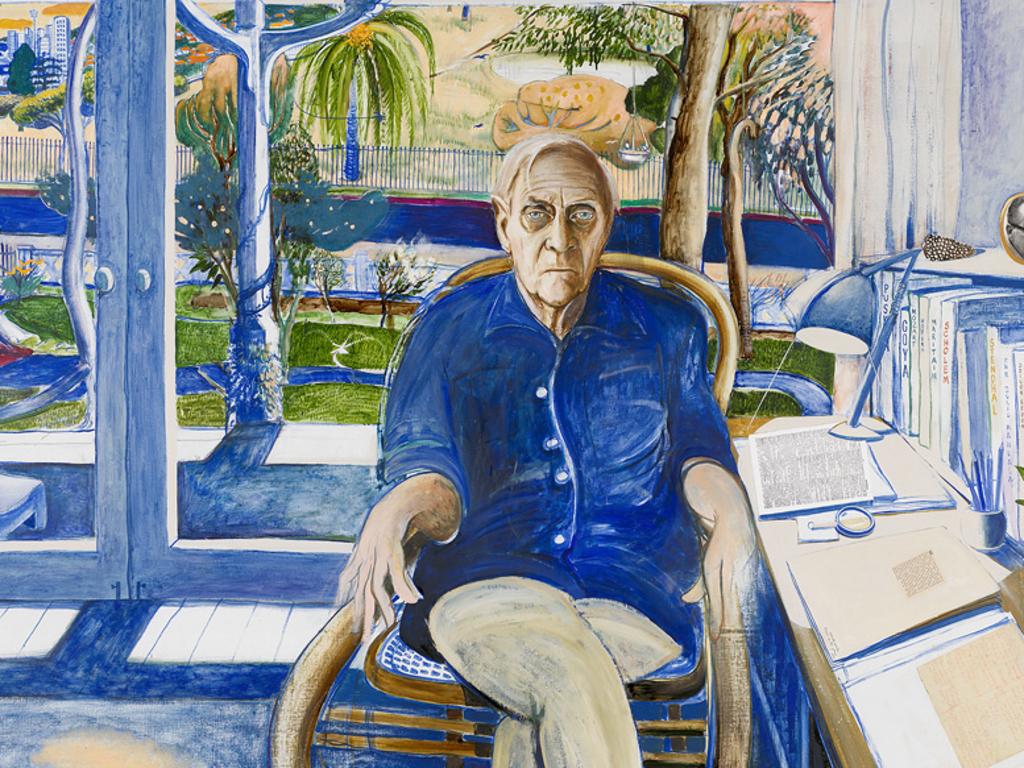

Patrick White, too, not only won the Nobel Prize but became Australian of the Year, a coup unimaginable for a writer today. And the new director of the National Gallery of Australia, James Mollison, bought one of the linchpins of New York modernism, Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, for $1.32m.

Like the departure of the Opera House’s Danish architect, Jorn Utzon, in 1966, the purchase of Blue Poles was as divisive as it was definitive. At stake were fundamental questions, like what kind of country Australia was and should be, and what role art played in building our national identity.

A single comment in John Weiley’s 1968 masterpiece Autopsy on a Dream, a documentary about the controversy surrounding the fledgling Opera House, captures the gulf: “Why do we need culture?” a bemused young woman replies when asked about the building. “We have beaches!”

On the other side of the equation, culture wasn’t just changing; it was on the march, as the public demonstrations in support of Utzon indicated. And art with it.

Kaldor had followed up Wrapped Coast by bringing to Australia in 1971 Swiss curator Harald Szeemann, who forged the model of the modern star curator, scouring the world for trends, which the Biennale would adopt in time and in turn “model” to a world of proliferating biennales.

It’s probably symptomatic that the year of Szeemann’s visit was also the one in which Belgiorno-Nettis suspended the old-school Transfield Art Prize.

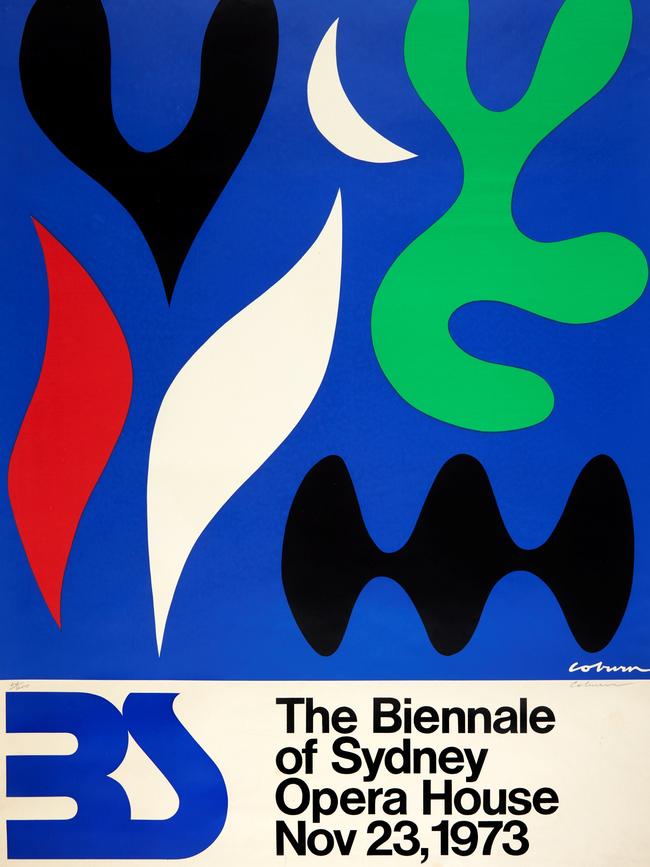

“Keeping pace with art is rather like chasing the end of a rainbow,” he would say two years later, at a March 1973 press conference. Held in a foyer of the yet-to-open Opera House, the event marked the launch of the vehicle he had chosen to chase that rainbow instead, “The Art Biennale of Sydney”.

In the lead-up to the announcement, Belgiorno-Nettis had been doing what he did best: agitating, improvising a way forward. In September 1972, one of his Transfield advisers, Pamela Harrison, credited as the Biennale’s first exhibitions officer, had put together a proposal for a predominantly Australian biennale to be held at the Opera House during its opening season, which would include one other country.

The winner would get a $6000 prize and a public commission, such as a mural for the big news of the day, the Eastern Suburbs Railway. And the NSW government should be asked to defray the considerable expense, given that Transfield could “easily fall on hard times” Harrison noted, adding: “I think the Minister would enjoy being handed the possibility of a real cultural event for the Sydney calendar”.

That event had taken a very different shape by the time it was officially announced 18 months later. By then, the Art Biennale of Sydney was non-acquisitive. No prize would be offered, nor was judging involved. And it would be firmly international, modelled on Venice and Sao Paulo, with the 30 invited artists split evenly between Australia and the world.

The Transfield Art Prize had been Australian, but always with an international judge. Through it, Belgiorno-Nettis “started getting the sense, the flavour, of the international”, his son Luca says. But those overseas biennales were put together over two years, by a staff that would double to 20 as the event approached. The first Sydney Biennale, in contrast, was cobbled together in eight months by two or three part-time Transfield staff, led by Franco’s put-upon executive assistant, Tony Winterbotham, a former military commander.

With Winterbotham co-ordinating a tiny team that included Harrison and socialite PR consultant Diana Fisher, Belgiorno-Nettis improvised all the way to opening night.

Not quite two months after launching the Biennale proposal, Transfield announced that the Australia Council, which Whitlam had relaunched just four months earlier, would contribute $10,000 as its first major activity. It had also nominated a committee to work with Transfield and the NSW government, chaired by James Gleeson, director of the Dobell Foundation (of which Franco was a trustee), and including James Mollison and artist RonRobertson-Swann, a founding member of the Australia Council’s new Visual Arts Board.

Transfield had guaranteed $25,000 and the federal Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade would contribute $4500. As for the hoped-for NSW government’s support, it would be limited to refunding the venue cost.

“The short story is it ended up landing on the table of the (VAB) of the Australia Council,” recalls Robertson-Swann. “We came to Franco’s rescue because he was stumbling around a bit doing it through governments and foreign affairs. He had extraordinary flair, but he wasn’t getting a lot of satisfaction from those contacts, and the embassies, and he wasn’t good at judging those things.”

By June, the international component had been significantly diluted and outsourced, with the panel selecting 23 Australian artists and DFAT issuing invitations to 13 countries, whose embassies selected the artists (only Cultural Revolution China declined). By September, Belgiorno-Nettis, now credited as the Biennale’s director, announced the new prime minister would himself open its first edition.

Along the way, the Biennale’s purpose had been clarified: “To draw Australian artists into the world’s cultural stream so that they may benefit from seeing and talking to prominent artists of international standing whom we hope will visit future Biennales,” and creating “a cultural focus in the Pacific Basin” that would “attempt by leadership to co-ordinate the progressive trends of the various cultures in the area”.

However, 22 uniformly pre-eminent, exclusively male Australian artists were chosen to fulfil the Biennale’s stated aim of providing “an outstanding and well-balanced exhibition”. As critic Bruce Adams noted at the time, the likes of Fred Williams, John Olsen, John Brack, Sydney Ball, John Firth-Smith, Fred Cress and Robert Klippel were all names who “easily (fitted) into the mainstream of art up to the late 1960s” rather than the 70s. Even Brett Whiteley was a little too contemporary. As for the international component, only a major Clyfford Still, 1955-H, gave what one critic referred to as a whiff “of the big time”.

Whitlam opened the first Biennale of Sydney at a party for about 100 guests, mainly politicians, business leaders, Transfield clients and representatives of embassies, the Italian community and the unions, on Friday, November 23, 1973.

A Transfield promotional film captured the moment: “And now, with the late afternoon sun streaming onto the Opera House, the moment of truth is near,” the voiceover says. “Guests arrive passing at the entrance a welcoming sculpture by Robertson-Swann … (the PM is) greeted by Franco Belgiorno-Nettis and (Transfield co-founder) Carlo Salteri … and so the Biennale is born.”

The reality was less mythic. Lighting was still being adjusted at the press preview, as Robertson-Swann helped Japan’s Minami Tada, the only female artist in the Biennale, to assemble her glass-and-plastic sculpture Poles, while, as the film intoned, “behind them pictures seem to glow from the dark walls in a setting designed by Robert Haines”. No amount of adjustment or design, however, could remedy the essential unsuitability of the “unattractive and inflexible” hall itself, as Sydney Morning Herald art critic Nancy Borlase wrote.

Adams agreed that the paintings were “so crowded they vie with each other for attention”, the sculptures “scattered almost incidentally around the darkened interior of the hall”.

Sandra McGrath was blunter still: “To anyone familiar with the famous, tempestuous, sprawling Biennale of Venice, the Sydney Biennale could only be irritating and inadequate,” she wrote in The Australian, condemning the show’s overall “impression of haste” and token internationalism.

“Only the dramatic shimmering glass-and-plastic sculpture of Japan’s Minami Tada and the large black-and-brown-streaked Clyfford Still canvas convey what the biennale should have been about,” she wrote.

Bluntest of all was the future director of the National Gallery of Victoria and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Patrick McCaughey.

“The best thing about the Sydney Biennale is its name,” he declared in The Age.

Promising “a survey of recent international art and local productions along the lines of the great exhibitions staged biennially in Paris, Venice and Sao Paulo”, the inaugural outing turned out “to be no more than a glorified mixed exhibition with some token international participation (which) puts further distance between the name and the action by cramming itself into the black and crypt-like space the Sydney Opera House is pleased to call an exhibition gallery.”

Other critics saw the Biennale as an extension of the sort of compromise that characterised the Opera House. Magnificent on the outside, the building featured, art critic John Henshaw wrote, “a peculiar kind of Hoyts jelly-mould Art Deco inside, where the political influence took charge”, something he saw as summing up the Australian viewpoint: “great outside, full of extrovert promise, inside full of confusion, superficial, materialistic, rigid”.

It was that view point that Whitlam hoped the Opera House and the Biennale would begin to change.

“There remains an invincible element of philistinism in all societies, including our own, that exhibitions like this will help to break down,” Whitlam told the crowd. “The fact that none of these works are judged, and that no prizes are awarded, reflects the fact that in the highly experimental world of modern art comparisons between individual works are difficult. There must always be a place in art for what is challenging, provocative, unconventional, even baffling,” he said.

Having been excluded from the main opening festivities a month earlier by the state Liberal government, the opportunity had been irresistible for Whitlam.

“At last I find myself at an opening ceremony at the Sydney Opera House where I’m not left out in the cold,” he quipped. “I hope no one will accuse me of stealing the limelight from (then premier)Sir Robert Askin. He manages these affairs more lavishly than the Transfield organisation.”

As for both the NSW premier and the Minister for Cultural Activities, far from relishing the opportunity of “a real cultural event”, they had declined the invitation.

“I remember it being rather a pompous affair,” recalls Penelope Seidler, one of the few who has seen all 23 Biennales over half a century.

“It was black-tie and there were lots of speeches and celebrity. I do remember Gough Whitlam, of whom I was very fond, and Franco Belgiorno-Nettis, with whom we were friendly, and wondering what it was all about, because it was numero uno. When we looked at the art, there was some sort of Asian context as I recall, but I don’t remember that we were very impressed.”

Typically, Margaret Whitlam ensured the evening didn’t get too carried away with itself. Guests were invited to participate in Melbourne artist Bob Jenyns’ First Lesson – inspired by the artist’s initial encounter with a naked woman in a life-drawing class at 16 – which consisted of three easels, paper and pencils, and a “very pink plaster female nude reclining on a mattress”, as one paper described it. Fred Williams declined to participate. Someone else scrawled “the biggest tripe in years”.

The prime minister’s wife, however, threw herself into it. “I’m doing all the clean bits,” she announced, as she knocked out what one journalist judged “quite a good drawing”, immediately snapped up by dealer Rudy Komon.

Overall, though, the show just “wasn’t particularly impressive”, McGrath says now, adding: “there were so many other things going on, such as James Mollison and the NGA, which had just bought, also in 1973, Willem de Kooning and Brancusi and Malevich. All these things were really exploding like fireworks.”

Indeed, one of the larger explosions was taking place just up the road at the AGNSW. Recent Australian Art, staged for the festival that accompanied the opening of the Opera House, was much closer to what the Biennale would become. “It hugely upstaged the Biennale,” the show’s co-curator Daniel Thomas says with unconcealed delight half a century later.

“Unless more money and more space and more time are available for the next (biennale), it is not worth doing,” McGrath wrote at the time. “The next biennale should be at the AGNSW using adjacent parklands and the state government would have to decide to involve itself with such a high venture”.

After it was over, embassies wrote to ask how they could be included. The British Council demanded information about the Biennale and asked why the UK had not been asked to participate. (It had been, by Patrick Heron’s Big Cobalt Violet.)

The Parmelia Hotel asked if the next Biennale might be held in Perth, and Fred Williams (who had been upset by Robertson-Swann’s hang of his Triptych 1970 Landscape) wrote to congratulate Belgiorno-Nettis and wish him the best for the next iteration in 1975.

All up, Belgiorno-Nettis was pleased. He wrote to James Fitzsimmons of Art International to thank him for running Elwyn Lynn’s article on the first edition.

“It is not only a very thorough dissection of the exhibition but it gives the Biennale a perspective which was lacking in local commentary,” he wrote.

“As such it will also play a considerable part in shaping the Biennale’s future and help give it the impetus to grow and improve. There is plenty of room for both, we realise; but such enterprise has to start somewhere.”

Edited extract from Turbulence & Transcendence: Biennale of Sydney The First 50 Years, by Brook Turner, published by Black Inc, February 25, $299.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout