John Kaldor: 50 years of making art public in Australia

Fifty years ago John Kaldor began introducing international contemporary artists to Australia.

John Kaldor has been one of Australia’s most prominent and generous art patrons for longer than most of us can remember. For half a century, his Public Art Projects have brought to Australia a variety of contemporary artists although the 1984 project, exceptionally, took the form of exporting three Australian artists to New York. Altogether, there have been 34 projects over this period, and the present exhibition represents the 35th.

This latest Kaldor project is in effect a retrospective of the whole preceding half-century, entrusted to an English artist, Michael Landy, who has come up with the idea of presenting the projects in small boxlike rooms, recalling the archive boxes in which documentation and correspondence pertaining to each of them would be stored, but also because the very term “archive” has become something of a buzzword in recent art writing.

These boxes are deliberately presented in random order, and oriented in different directions, so that one constantly has to walk around them to find the way in. The effect is chaotic and claustrophobic at the same time; considering that the rooms are in effect presented as a gaggle of little houses, one is struck by the way they form the opposite of a village: there is no sense of organic connection or belonging or common space between the individual structures.

Of the projects themselves, some have naturally been more memorable and effective than others. Looking back at any series of contemporary art projects is like looking back at old Biennale catalogues and realising how many artists were taken seriously for a time, supported by institutions and written up by earnest commentators, only to vanish from the scene a few years later.

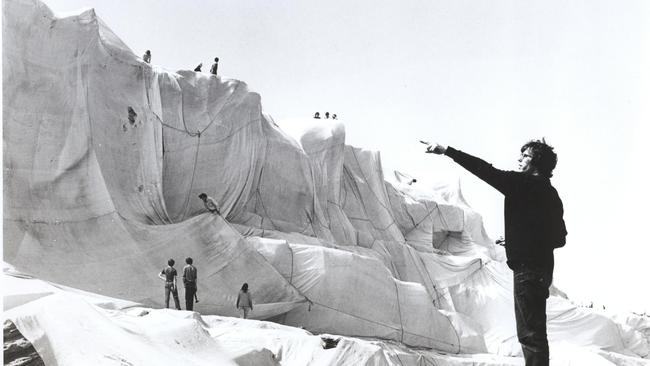

In this case, the most impressive and successful of all the Kaldor Projects – and the one that made the greatest public impact – was the first, when Christo wrapped the cliffs of Little Bay in Sydney in 1969. In 1994 he acknowledged the role of his wife in helping to make his works, so that even earlier ones like this are now attributed, slightly anachronistically, to Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The wrapping of Little Bay was so striking because of its timing as well as its conception. Australia had never seen a modern art project on this scale before, and we were not accustomed to huge amounts of money being spent on art of any kind, let alone ephemeral artistic manifestations. And there was virtually no corporate sponsorship for this kind of activity; today, when large corporations regard art sponsorship as part of brand-building, we have become naturally more jaded.

It was an interesting project too because it arose from a purely aesthetic impulse; Christo was not trying to make any ideological point or convey any social message. He was simply drawn to the idea of wrapping a huge stretch of rocky coast, and the result was imaginative and suggestive: it evoked themes of concealing and revealing, as well as recalling all the associations we have with wrapping, from gifts to parcels in the post to the swaddling of infants or the shrouding of the dead.

Finally, as I pointed out some years ago, Christo’s project was almost unique in being a significant work of international art first made in Australia – and thus attracting much interest around the world – whereas most other artists brought works or variants of works they had already done elsewhere.

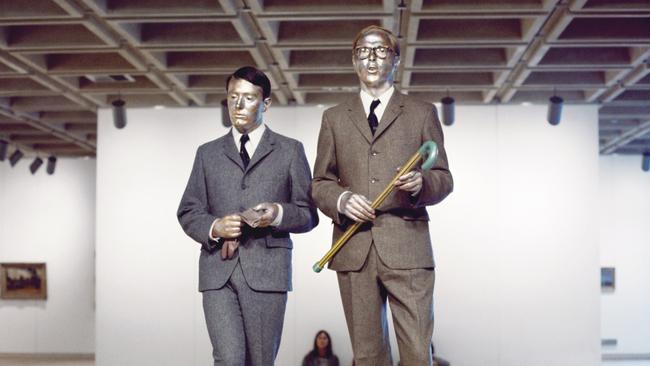

Harald Szeemann, two years later, probably represented the low point of public impact, but Gilbert & George were memorable as the Singing Sculptures in 1973, even though they were repeating a performance originally carried out in 1970 in London. They adopted the roles of two arch-conservative and conventional English gentlemen, a long-term performance that was to become their lives. In later years, Richard Long’s contribution in 1977, consisting of a walk in a straight line for 100 miles – 50 out and 50 back – documented along the way with photographs, was one of the more thoughtful, although it probably made little impression on the general public. It was a work in which there was little to see but much to think about, or perhaps rather to dwell with imaginatively.

Jeff Koons’s colossal Puppy outside the MCA in 1995 was exactly the opposite. It was seen and photographed by probably millions of people but, like all of Koons’s work, it was inherently meaningless; a bottomless pit of vacuous spectacle, one might say, which attracted spectators irresistibly, but left them with nothing. A more recent highlight was Bill Viola, in Sydney in 2008 and Melbourne in 2010 with a pair of remarkable video works, Fire Woman and Tristan’s Ascension. In 2013 13 Rooms represented a survey of the history of performance art, but unique in that famous performances of the past were re-enacted, alternating with some new pieces. This was followed in 2015 by a large-scale event at Pier 2/3 in Walsh Bay in Sydney, combining both new and old works by Marina Abramovic.

Ten years ago in 2009, Tatzu Nishi’s War and Peace and In Between at the Art Gallery of NSW was combined with a 40-year retrospective of the Kaldor Projects. Nishi built what looked from the outside like boxes around the two colossal equestrian statues outside the Art Gallery. When visitors entered the boxes, though, they found themselves inside a couple of luxury hotel rooms, with massive bronze horsemen mounted on the beds.

Nishi made us look anew at sculptures we were accustomed to walking past distractedly, but which now forced themselves on our attention with their overbearing and emphatic forms, as well as the incongruity of their presence in such an environment. But striking as these were, they were ultimately versions of the same idea – of boxing in a familiar statue and confronting the viewer with it at a different scale and in unfamiliar proximity – that he had already applied on several occasions around the world.

It was a reminder of the way the contemporary art world had changed since Kaldor first sponsored Christo: contemporary art was now a big business, involving a great deal of money, making the top dealers and some of their artists very rich, supporting the corporate image-building of big corporations, and exhibited through an international network of biennale-type exhibitions that needed a constant flow of content.

Artists like Nishi, while neither very deep nor particularly original, had become vital as reliable providers of the product the system needed to keep running. A formula like his could be repeated with almost exactly the same results indefinitely in any important global city that had prominent public monuments from the past few centuries. He was one of the B-grade contemporary artists who form the backbone of most biennali, which are led by a few A-grade stars then filled in with various C-grade individuals to make up the numbers and obligatory quotas.

The best of the works Kaldor sponsored could be regarded as interventions that served to disrupt the banal routines and habits of a mechanical and utilitarian world. Christo, for example, makes the viewer wonder why he is wrapping a coastline, and by extension why we wrap things at all. What does it mean to cover things and tie them up? What lies inside things parcelled in this way? What happens when we unwrap a parcel? A set of implicit and mostly unarticulated questions that slightly loosen the sclerotic habits that serve as shortcuts in a utilitarian world.

In this form, however, in this non-village of boxes, original works preserve little of that power to disturb and occasionally delight. The vestiges in each room sometimes offer a glimpse of the original work, but will often leave the layman unenlightened. At the same time the overall effect is of a labyrinth that is in the end rather claustrophobic and feels more than anything else like an allegory of the art business: separate, alienated, lacking any sense of human community.

At a deeper level, the very strengths of the avant-garde work of the late 20th century also point to its weakness. At its best, as I observed, it disrupts the lazy and unconscious habits of a utilitarian society and opens us to the possibility there is more to life than going to work, making money and consuming goods.

But disrupting habits of inattention and unconsciousness is not the highest ambition of art. Art can open us to a deeper awareness of the natural and human world. But the latter part of last century, until the revival of the conservation movement, was a period singularly alienated from nature, and postmodernists sneered at the idea of any human connection with a deeper and ambient living world. At the same time, it was the low tide mark in the practice of those media, like painting, which could be vehicles of more subtle forms of apprehension of the world. We were more or less stuck with photography as the dominant medium for representing the world, at the same time as losing faith in the veracity of photography – which became more and more compromised as we moved into the age of digital manipulation of images.

So when we survey this art of the end of last century, we are confronted by a series of ironic or deconstructive interventions that serve to destabilise or question our habits of ideology, false consciousness or merely incurious complacency, but we don’t find many cases of artists trying to rebuild a language for representing the world, in particular through the primary media of drawing and painting.

The contemporary culture industry is reluctant to embrace the art of painting except in parodic form; this is ultimately the symptom of a lack of courage; other media can evade the reckoning with history, but painting has to stand up to comparison with the very artists who helped build and define our culture.

-

John Kaldor: Making Art Public. Art Gallery of NSW, until February 16

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout