Sydney Biennale: art festival out of the box with archive installation

The Sydney Biennale’s archives offer a revealing insight into our artistic and political history.

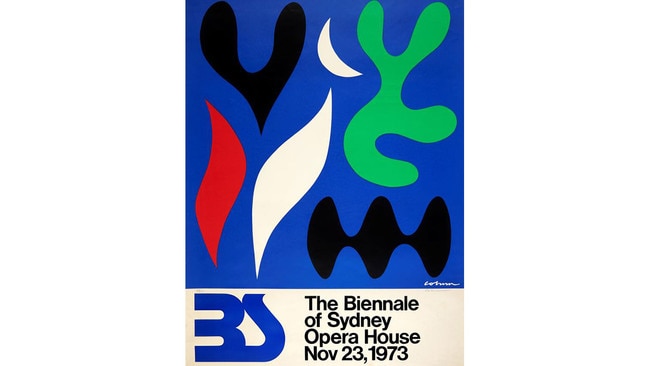

In January 1973, Anthony Winterbotham, the administrative director of the inaugural Biennale of Sydney, wrote to the event’s founding governor, Franco Belgiorno-Nettis, with news from abroad. Contemporary art shows in Paris and Venice, he wrote, were being interrupted by “rebel students” calling for all kinds of reform. He must have figured this was important to know, since their new show was opening at the Sydney Opera House later that year, drawing together 37 artists from 15 countries. “It would appear that we have avoided the pitfalls complained of but it is probably worth watching out for,” he advised.

In a sense, Winterbotham was right to be wary. In its 45 years, the Sydney Biennale has proven to be a magnet for politics, and to look back over its evolution is to chart social anxieties and cultural debates over time. In 1976, for instance, a petition circulated across Sydney — “Confront Fraser with your rage!” — detailing a protest against the prime minister, who was scheduled to open the latest Biennale a year and a day since the Dismissal.

In April 1982, NSW premier Neville Wran criticised his own police for seizing a sexually charged painting by Juan Davila after a complaint by Fred Nile. “I don’t think art has got anything to do with the vice squad,” Wran said.

Perhaps the most consequential action took place in 2014, when activists protesting against Australia’s treatment of asylum-seekers forced the Biennale to cut ties with its founding sponsor, Transfield Holdings, over its connection to offshore detention centres. Luca Belgiorno-Nettis stepped down as chairman in the hope that some “blue sky” would open over the event. “There would appear to be little room for sensible dialogue,” he said, “let alone deliberation.”

The latest Biennale of Sydney opens on Friday and features the work of 70 artists and artist collectives from more than 35 countries across seven locations. It’s called Superposition: Equilibrium & Engagement, and artistic director Mami Kataoka has combined Australian talents such as Brook Andrew, Yasmin Smith and Marco Fusinato with an international contingent that includes Chinese provocateur Ai Weiwei and British performance artist Oliver Beer. Kataoka also has included on the program an archival installation, downstairs at the Art Gallery of NSW, that concerns the mechanics of the Biennale itself.

The installation is a product of a project that began a little more than two years ago, when the organisation’s archive was given to the Art Gallery of NSW, a prominent venue for the Biennale since 1976. Gallery staff, led by archivist Steven Miller, have been working steadily through the 1000 boxes ever since and so far have processed about 200. The AGNSW used the Biennale gift to launch a broader initiative: the National Art Archive, which holds the material of more than 200 artists and galleries. (Far more than just assorted papers, it even includes shoes belonging to Lloyd Rees and dresses made by Thea Proctor.) It’s still early days, but next month the gallery will publish about 2000 pieces from the archive online, including a selection of photographs by Robert Walker. For Miller, archival material is like the “underbelly of an institution”, telling multiple stories from multiple angles, not always the official versions.

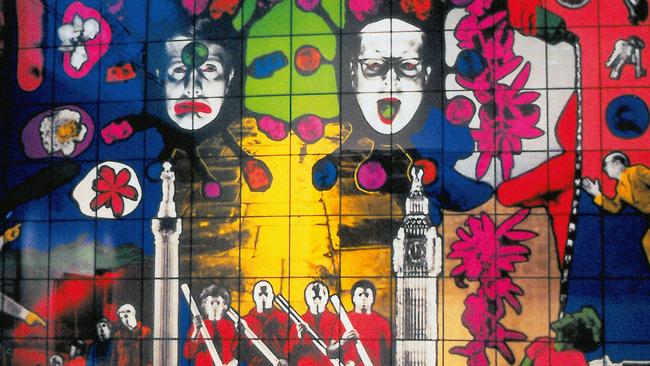

The Biennale installation is made up of various pieces of correspondence — letters, faxes, telegrams, informal scribbles — from each stage of the event. Stelarc and Yayoi Kusama are among the artists who have written to curators to discuss the presentation of their work, and there are letters from local artists taking issue with certain decisions along the way. (At one point, Franco Belgiorno-Nettis attempts to placate a group of irate Melbourne artists: “I can assure you that recent Australian art is in no sense being treated as a second-class citizen in the forthcoming Biennale, and that its scope and diversity will be well exhibited. I feel you slightly misunderstand the purpose of the Biennale, which is to provide a unique opportunity for artists and the public to become aware of cultural trends taking place in the rapidly changing world outside.”) The presentation also includes documentary film footage, reports to boards, catalogues, posters, financial applications, press releases and newspaper clippings.

All up, it tells a fascinating story of changing tastes and opinions, including greater representation of indigenous artists. Former Biennale managing director Paula Latos-Valier helped compile the material through the years but cautions against looking for any coherent narrative or “order in chaos”. “We all have different personalities, different allegiances, different interests, so of course you’re going to get a huge spectrum reflected in any large contemporary art exhibition, and it will be highly diverse,” she says. “It will be black at one end and white at the other and all the colours in between.”

Latos-Valier joined the organisation in 1981 and went on to run nine shows. She says the archive illuminates shifting ideas about what makes contemporary art, from Fujiko Nakaya’s “fog sculpture” (1976) to Krzysztof Wodiczko’s projections on to the city skyline (1982) to Hermann Nitsch’s “blood paintings” that prompted another visit from the vice squad (1988) to Ai Weiwei this year. “It’s all so different and so personalised,” she says, “so it’s very hard to draw a line through any of that except to say that all these people are incredibly engaged, physically and intellectually, in the world around them and in people’s reactions to that world.”

Given the characters involved, the archive is full of colourful insights into the personalities of artists from around the globe. In September 1978, Marina Abramovic and her then partner, Ulay, wrote to Biennale director Nick Waterlow from Amsterdam about the work they would be showing the following April. In a letter packed with fabulously irregular spellings, they propose a series of lectures and performances, as well as film screenings, and hoped to arrive in Sydney a week before the opening to prepare: “In any case, it is not possible now to discribe a performance we will do in about half a year, we hope you understand this. Esspecially if we whant catch a sertane fact, which will bring more a authentic caracter about the country, city, location into the piece …”

The letter also conveys their excitement about the trip itself (again with original spelling retained): “We are realy crazy abaut going to Australia (who wouldn’t). So we try to immagine about it to get even more surpriced …”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout