Brett Whiteley catalogue reveals skills of one of our great painters

Over the last few years a number of dubious artworld figures — often with previous form in the business — have been involved in passing off fake Whiteleys.

One of Antoine Watteau’s most fascinating paintings is L’Enseigne de Gersaint, made in 1720 only months before his death and today in the Charlottenburg in Berlin. It was intended as a sign to hang outside the shop of his friend, the art dealer Edmé-François Gersaint, and depicts its bustling interior, with collectors and connoisseurs examining pictures for sale or watching their purchases being packed for delivery.

The same Gersaint became, in 1751, the posthumous author of what is said to be the first catalogue raisonné, that is to say an exhaustive listing of all the works — or works in a particular medium — reliably attributable to a single artist. Gersaint’s Catalogue raisonné de toutes les pièces qui forment l’oeuvre de Rembrandt, despite its title, is in fact concerned only with his prints. The book can be read online, but it is not illustrated, so each piece has to be laboriously described.

The author of the introduction writes admiringly of Gersaint’s earlier non-monographic catalogues for sales of important private collections, which he considers a valuable resource for art-lovers seeking to educate themselves. It is clear too that the need for critical catalogues was felt particularly in the case of a medium which is inherently multiple and moreover often exists in different successive states.

Works of this kind can more easily be copied and passed off either as originals or as variant states, and old plates can even be reworked or recut after the artist’s lifetime to produce further saleable impressions. But critical catalogues are also important for paintings, and Claude Lorrain’s Liber Veritatis, a personal illustrated record of every picture he painted from 1637, was a precursor. In more recent times, the scholarship of historians from Bernard Berenson onwards helped to redefine the oeuvre of Titian and other Renaissance masters, which had become bloated with copies, workshop repetitions and hopeful misattributions.

The same concern to establish authenticity explains the need for comprehensive catalogues of modern artists. In Australia the work of Brett Whiteley has been a favourite target for forgers, probably because he did a great deal of work (it is always easier to slip a fake into a vast corpus), employed characteristic stylistic flourishes amounting at times to self-parody, and sells to collectors for very high prices because his best-known work is ostensibly modern without being inaccessible.

Over the last few years a number of dubious artworld figures — often with previous form in the business — have been involved in passing off fake Whiteleys, inevitably through private transactions that avoid the scrutiny to which works are exposed when sold at auction and published in the catalogues of auction houses.

The artist’s widow, Wendy Whiteley, has repeatedly cautioned collectors about buying pictures that have not been approved by her or subjected to specialist scrutiny.

One example of this process successfully exposing a doubtful work was in the case of Moonlight on Lavender Bay, listed for auction in 2017 but withdrawn before the sale and, contrary to what was at one point claimed, is not in the new catalogue raisonné.

The story of three other pictures illustrates what can happen when you part with millions of dollars to buy undocumented pictures in private deals. In 2007, one collector paid $2.5m for a Blue Lavender Bay; he has apparently not been able to recover his money.

In 2009, another paid $1.1m for an Orange Lavender Bay. After Wendy Whiteley declared it too a fake, the matter was referred to the police; this individual got his money back in 2010, presumably in exchange for withdrawing the charge.

Meanwhile yet another painting, Through the window, Lavender Bay, was offered for sale but the deal fell through because of doubts about its authenticity.

Then Victorian police began an investigation in 2014 which culminated in Australia’s biggest art fraud trial in 2016. Peter Gant and Mohamed Aman Siddique were convicted and sentenced to jail, although their convictions were overturned on legal technicalities during an appeal in 2017. Needless to say, none of these pictures is in the new catalogue. Nor is Bather and Garden, which was sold to another private collector in 2006 for $1.5m.

But meanwhile some of the same artworld personalities reappeared in a scandal last year about a fake or undocumented Howard Arkley — another painter whose mannerisms are easy to pastiche.

So it should be fairly obvious by now that if you are seized with the urge to acquire a Brett Whiteley painting and a dodgy fellow who looks a bit like a bookie offers to sell you a terrific view of Lavender Bay at mates’ rates for a couple of million, you should probably tell him you’ll call back and start by investing in a copy of this substantial work which, although very expensive as books go, could save you from far more costly mistakes.

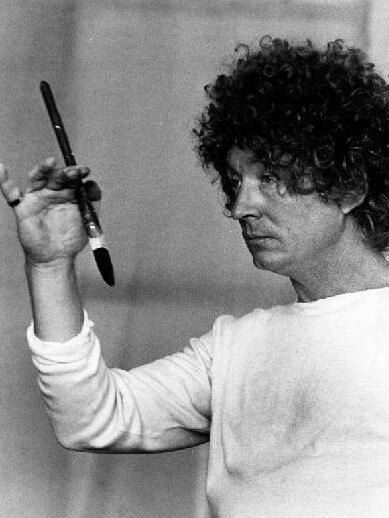

Financial considerations aside though, this is a very impressive achievement and a beautifully produced set of books. Kathie Sutherland has worked on the immense project for seven years, and has gained in the process an unparalleled expertise in Whiteley’s corpus.

Unlike Gersaint, she has had the benefit of the finest and most accurate colour reproductions. Nonetheless, her written accounts of the individual works, contained in volume VII, are even longer than his when one takes into account technical description and provenance, as well as exhibition and publication history.

In fact it must be said that Sutherland’s publishers, Schwartz City (part of Black Media), have excelled themselves in the production of a monumental work weighing some 25kg and comprising seven volumes, which are not only presented in a boxed set, but a box which itself has separate internal compartments for each of the volumes, which vary considerably in thickness according to the amount of work belonging to the period or category that it covers.

The second — and slimmest — volume is a high point with its enormous fold-outs, each of which takes the full length of a generous dining-room table to open fully, of The American dream (1968-69) and Alchemy (1972-73). This may seem extravagant, but there is in fact no other way to reproduce these enormous works — The American dream is almost 22m long — in a way that is intelligible to the viewer.

The first volume covers the artist’s work up to the end of the 1960s; in the earliest years it is fascinating to watch a voraciously energetic young mind seeking inspiration from all the contemporary Australian and other sources that could be relevant to his sensibility, from Drysdale and Friend to Dobell and Brack, and then gradually finding his way to his first recognisably personal manner.

By the middle of the sixties, now living in London, Whiteley’s work is dominated by the gruesome series devoted to the serial murderer John Christie.

What is perhaps most enlightening in the subsequent volumes, number III devoted to the 1970s and IV to the 1980s, is to follow all the work in roughly chronological order, year by year, rather like a diary. Sadly, it is a diary increasingly dominated by the nightmare of heroin addiction. For some artists, drug addiction may be less intrusive or more manageable; for Whiteley it was destructive and uncontrollable because it was so inseparable from his artistic process and the ecstatic and intoxicated state in which he found creative inspiration.

The best companion to all this material, incidentally, is the recent biography of the artist by my former colleague in these pages, Ashleigh Wilson: Brett Whiteley: Art, life and the other thing (Text 2016), which so sympathetically and insightfully follows the story of a young and talented artist in a quest that ultimately loses its way and ends tragically.

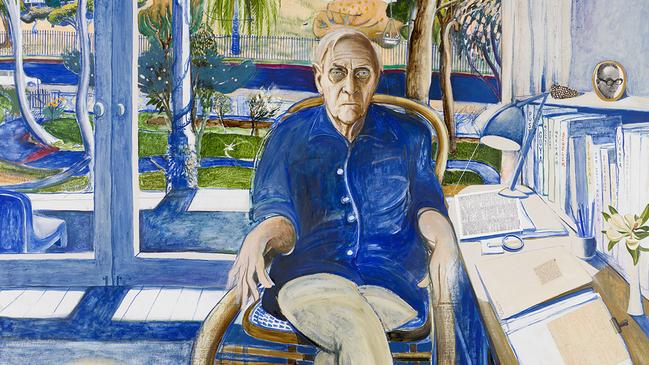

Several themes are intertwined throughout these volumes: landscape and nature, vivid and intuitive drawings of birds and animals, and erotica. In all of them tireless energy expresses itself but seldom comes to rest in a poised and composed way — with occasional exceptions such as the memorable portrait of Patrick White at Centennial Park (1979-80).

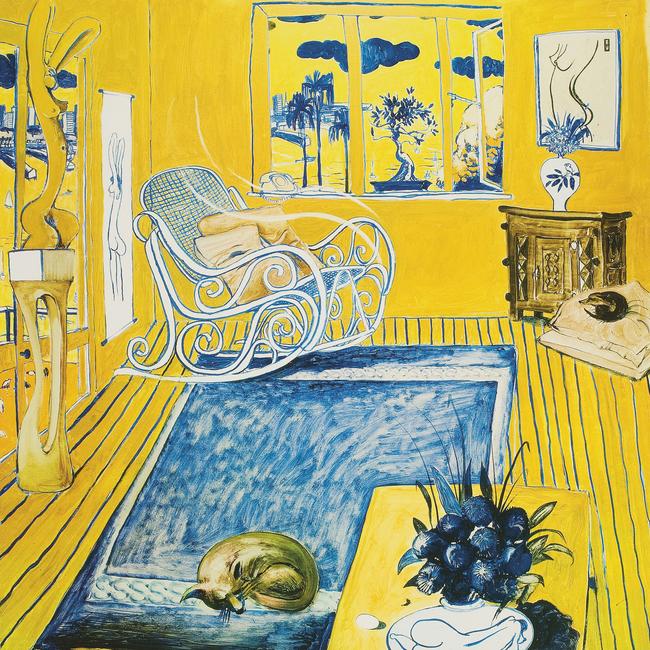

Perhaps the most notable thing revealed by this diary-like sequence, however, is the disjunction between what we could broadly call private and public images of the erotic, although the boundary is by no means a clear one. Whiteley’s oeuvre is filled with vivid and explicit erotic drawings of couples — or indeed threesomes — in bed, and these themes are central to the two enormous mural works already mentioned. Sexual desire, also a kind of intoxication, is the paradigm of all creative energy in his world.

But when we turn to his attempts at the nude, even from the 1960s and especially in the beach scenes and bathing figures of the 1970s and 1980s, this ease and spontaneity are replaced by a clumsy and often grotesque distortion: female figures who turn into little more than huge buttocks, or tangles of limbs that have too little relation to the structure of the human body to be expressive. This distortion seems to arise from Whiteley’s attempt to convert the erotic passion that he conveys anecdotally with such ease in his sketches into some higher, more impersonal and more permanent manifestation. It is as though he wants the erotic to become immanent in the very form of the body, to radiate from it, rather than to be literally illustrated.

He seems to be trying to achieve something like the mysterious and restrained intensity of Titian or even, much later, of Ingres in his Odalisques.

But Whiteley could never achieve this synthesis: the female nude, central to his oeuvre, remains his most unsatisfactory motif, because he can never see the body as anything but the object of his own immediate desire. All that happens when he tries to paint the female nude — as in all those beach girls in bikinis — is that they become painfully deformed and dislocated by the unsuccessful attempt to restrain or subsume the expression of desire. Most significant is the constant reduction of the size of the head, compared to the exaggeration of the scale of the buttocks.

All this is, once again, even more inescapable when we see his work in chronological sequence, for Whiteley is more successful in representing places and landscapes, even if he has a tendency to be anecdotal, illustrative and formulaic. This is indeed why the fake views of Lavender Bay seen from his studio could seem as plausible as they did: he repeated such motifs too frequently and too carelessly.

Whiteley’s drawings of birds and animals are particularly striking: he enters into the being of these creatures and experiences the vitality of their unconscious experience in a way that his narcissism made impossible in the representation of women.

The female figure, although ostensibly his greatest source of inspiration, remained paradoxically inaccessible to him, objectified by appetite.