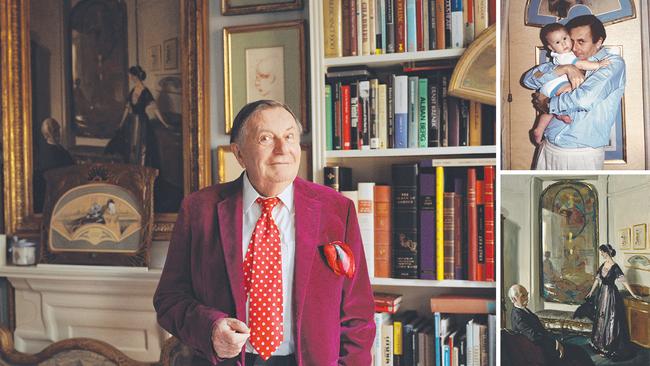

Intimate portrait of genius Barry Humphries, captured in the artworks and objects he truly loved

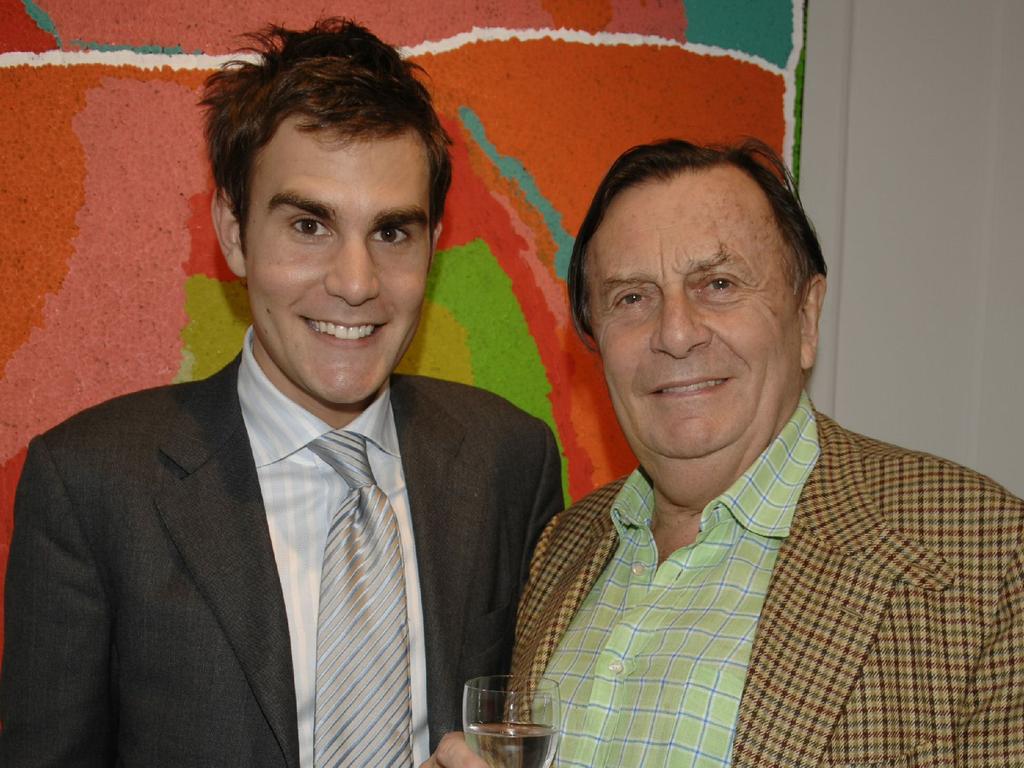

The late satirist and comedian Barry Humphries’ private collection of art and objects will be sold in London next month. His son reflects on his father’s passion for beauty.

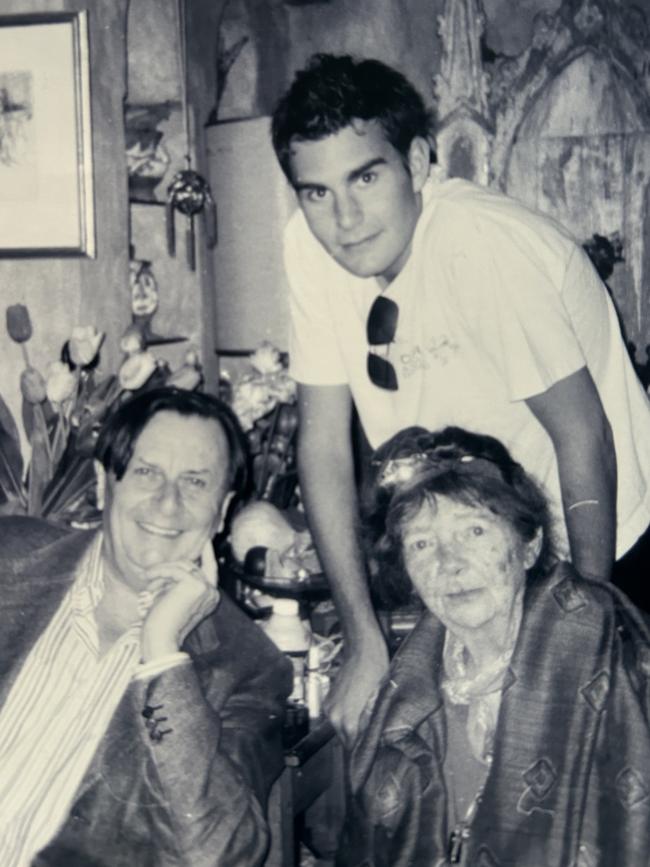

Art and books were part of my father’s life from very early on. Long before the stage and an interest in performance, long before Dame Edna Everage, there was an appreciation for art and words in their material form, dust-jacketed or framed. Just as all children are artists, they are, in a way, collectors also, keeping close their favourite toys and teddies. Dad just never grew out of it.

Much of his art collection and his library will be sold at auction in February by Christie’s in London. There are several hundred paintings and books that he acquired over the past 70 years.

Some he bought when still at university; one of them was bought in 2023, the year he died. Just as he never stopped touring, nor did he stop collecting.

As he would later do with box office receipts and film residuals, as a schoolboy he spent his pocket money on second-hand books, much to the disapproval of his mother, who was suspicious of anything unconventional or avant garde. “Do you have to buy those old bits and pieces? You never know where those things have been.”

He came home from school one day to find all his books gone. His mother had given them to the Salvation Army. Horrified, he asked why. “Because you’ve already read them.”

I’m convinced that his life as a collector was in a way an attempt to replace this lost childhood library.

In the Christie’s catalogue you will see a portrait in objects of my father, reflecting his taste and the very real love he had for these works and those that made them.

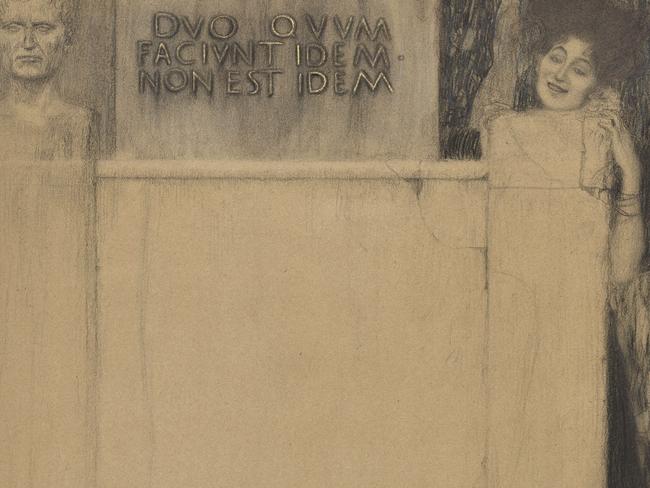

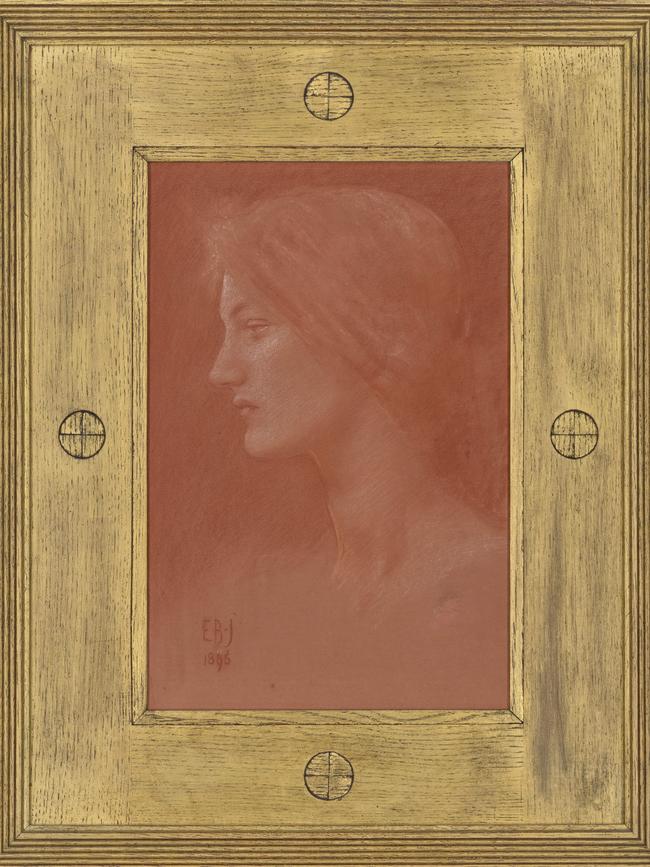

My father loved strangeness in art, which is what must have appealed to him about symbolism and artists like Klimt. He loved the occult and ghost stories. Both themes were well represented in his art collection and his library. All things spooky fascinated and amused him. I would joke with him that one day he’d “go ghost mode”, a joke that seemed to amuse him less and less the older he got!

Dad said his favourite teacher “smelt of art”, that is turpentine. He recounts in his first memoir, painting at eight years old on the banks of the Yarra river, where the Australian impressionists had painted half a century before in the 1880s and ’90s. There is a beautiful early Charles Conder painting in the auction. It makes its subject the very same landscape that formed the backdrop to Dad’s childhood.

It was in “The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition” of August 1889 and it hung at home in London. I like to think of him looking at it when he felt homesick or wanted to remember happy days as a child.

Conder left Australia for England in 1890 and rapidly enjoyed enormous success with his oil paintings and his more delicate and Japonist paintings on silk.

He was my father’s favourite artist, perhaps because he had both an Australian and a British life and you can feel that in his art. Soon after arriving in London, Conder found himself a central figure in Oscar Wilde’s glittering orbit. It was Dad’s early interest in the artist that led him to Wilde, first reading everything he’d written and later, when he was able, buying rare first editions and letters by him and his circle.

In Wilde, we have both comedy and tragedy. He gives us pathos and laughter; these formed part of Dad’s artistry also.

You will see no abstraction among Dad’s collection; he hated abstraction and lost interest in art generally if it was made after about 1950. He and our wonderful friend Margaret Olley shared this aversion to art made by people who they thought couldn’t draw.

Cy Twombly was a particular least favourite of theirs. “Nobody’s home,” Margaret would say pointing at one of his paintings. Whenever Dad came over, I’d make sure I had as many Twombly books out as I could, in order to annoy him. I’d also remind him that many abstract artists could draw, they just chose not to. Which infuriated him.

The poet John Betjeman was one of Dad’s greatest friends and one of his earliest supporters in England. He wrote, long before it came true, that Dad would be a huge star and that “he shares the tears of things, as well as the laughter”. Just as Wilde did.

Not unlike Conder, Dad’s success in Britain was rapid. His early if inconsistent triumphs allowed him to start collecting more ambitiously. There is a wonderful photograph by Lewis Morley of Dad at home in Little Venice taken in the late 1960s surrounded by Conder silk fans, many of which Dad managed to keep, despite being terrible with money, as many artists are.

To think about his career and his public life in tandem with this quite private passion as a collector is interesting. It was, after all, his professional success that enabled him, finally, to buy masterpieces and to create a proper library.

He needed a library in order to feel alive and inspired, just as he needed the stage and the audiences he loved and appreciated so much. I remember visiting David Hockney in Los Angeles a few years ago. David made several wonderful portraits of Dad, and of my stepmother, Lizzie. We were looking at some new paintings and he paraphrased Picasso: “When I paint I feel 30.” This could also be said of Dad when working. He was forever young on stage and said that Dame Edna could do things he couldn’t.

I’m convinced that when Dad saw what was to become his apartment in Switzerland, he looked at a huge wall and remembered, crated in a warehouse, his large painting by Jean Delville, L’oubli des Passions. Touring was an opportunity to keep collecting also and travelling all over America meant he could visit museums he’d always wanted to and indeed visit bookshops and private galleries.

The Burne-Jones charcoal was bought in Toronto, for example, its purchase facilitated by a residual cheque he’d got from Pixar thanks to his role as Bruce the shark in Finding Nemo. I love the idea of his work in a children’s film allowing him to indulge a passion he’d had since childhood.

In London at the home he shared with Lizzie, his wife of over 30 years, his books and art found their most permanent home.

His library was like something out of Huysmans’ symbolist novel A rebours, about a man who decides to spend the rest of his life in intellectual and aesthetic contemplation. Oscar Wilde loved this novel, about which he said: “The heavy odour of incense seemed to cling about its pages and to trouble the brain.”

Dad’s library had the atmosphere and indeed sometimes the literal smell of incense – exotic and heady, slightly dark and mysterious.

Dad loved inviting people over, sharing the library and the many stories contained, leather-bound, within. The library was a refuge but he was equally happy on a beach or with friends or painting.

His collection was an extension of his life, not its totality.

Given how much he liked the idea of ghosts, my family and I have discussed where his might be. I’m convinced he’d be outside, maybe on the beach at Mornington. He wouldn’t be in a darkened library. He looks so happy in the painting Arthur Boyd did of him in the bush with his oil paints no doubt smelling of turpentine. Perhaps he’s there.

I have made a career in the art world and this would not have happened without Dad’s knowledge of art and his infectious enthusiasm for it. I don’t think I ever thanked him in life for this gift, for the joy art and literature bring us is surely one, but I wish I had.

The last present he gave me was an illustrated children’s book called Honey Bear. He’d had it since early childhood and it somehow survived his mother’s book purges. He inscribed it to my young daughter Honey.

For me, it has a Proustian resonance and is a madeleine in paper form. From the start of his library, it is now the start of my daughter’s, and a reminder that we are but temporary, and temporal, custodians of art and books.

Barry Humphries: The Personal Collection. February 13, 2025.

www.christies.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout