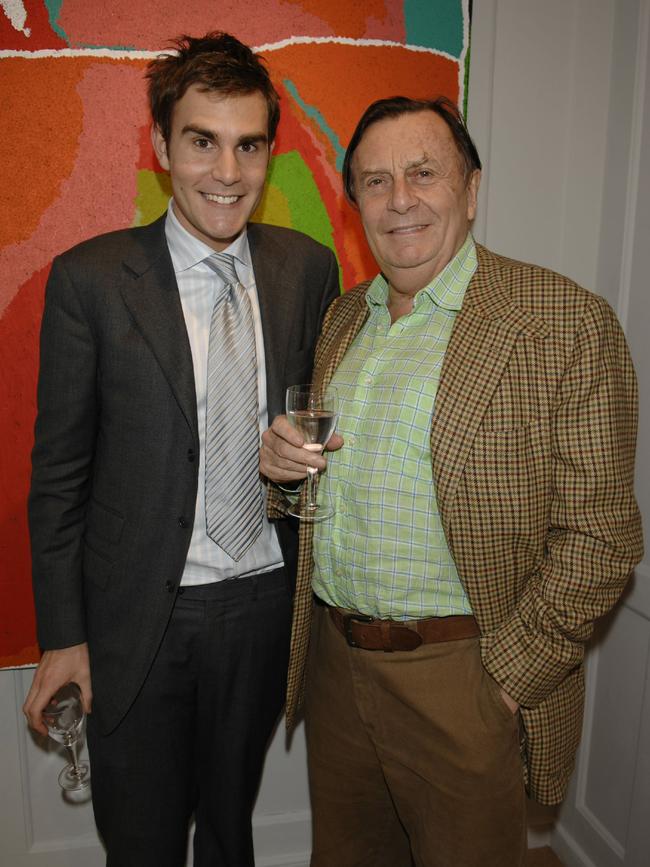

Oscar Humphries talks about collecting art with his father Barry Humphries

Barry Humphries loved buying art, painting landscapes and making friends with artists, says his son Oscar Humphries, who inherited the collecting bug.

As well as being one of the most deliriously funny entertainers of the past century, Barry Humphries was a connoisseur of renown. He didn’t collect art because it was fashionable, but because it spoke to his unique sensibility. His taste was for decadents and exquisites. A devoted bibliophile, he collected books in the tens of thousands. His library was legendary.

His mania for collecting was undimmed, even in the months before his death in April. Oscar Humphries suspects his father was calling book dealers “on the sly” from his bed at St Vincent’s Hospital when the family had left the room. On another occasion recently, Oscar showed his father a painting by Charles Conder that was coming up for auction in Sydney.

“His eyes glinted and we talked about it, and he said, ‘It’s not the right time’,” Humphries recalls. “I should have bought it … He really encouraged me in my own collecting and understood the recklessness and extravagance of it.

“He and I would look at things together, sometimes I would find things for him to buy, or I’d find things online. It was a lovely thing to share with him.”

Oscar Humphries, 42, is his father’s son in more ways than one. The collecting urge was passed on to the younger Humphries, who works in London as a curator and art dealer. He shares with his father a similar taste in the fine arts, although not in everything – “I think he was amused sometimes by the kind of art that I deal in” – and Oscar admits to not having his father’s ear for music. But it was almost impossible for Barry’s collecting not to have an influence on his son.

“He collected from when he was a schoolchild, and all the family photos I have of him and me as a kid are either indoors – surrounded by art and books – or at the beach,” he says. “It was a sort of binary life. It really is about galleries and home, and swimming.”

Humphries was formerly a magazine editor – at 25 he was the launch editor of Spectator Australia, and edited the British art magazine Apollo – but gravitated towards curating exhibitions and dealing in fine art and design.

“People used to say, ‘How did you get into this?’” he recalls. “I sort of fell into it, I didn’t know what to do. But of course, having a father who loved art must have been the catalyst for that. And to have such an important thing in common with someone is so special, because it creates a relationship beyond a fraternal one.”

The artist at the centre of Barry Humphries’ collecting – and with whom his son shares a given name – was Oscar Wilde.

“He had Oscar Wilde’s telephone book, and many of his works in first editions, inscribed to friends. Libraries are often very private things. Dad’s library consists of tens of thousands of books, so it has its secret corners.

“He attempted to organise the books, but it was Sisyphean in a sense. It would have taken years to fully understand that library, which he built over 60 years.”

Humphries also collected works by other artists in Wilde’s circle or acquaintance, such as the English-born Australian Charles Conder, and built what Clive James observed was the largest collection of Conder’s work: drawings, paintings, designs for fans, and his delicate, almost fey, paintings on silk.

“When Conder went to Europe they became very fashionable – he was a sort of chic figure,” Humphries says. “Conder married some money and lived very well in Chelsea and was friends with Oscar Wilde – there was a sort of vogue for these silk panels and screens and fans that he painted, and Dad loved them most of all.”

Humphries wasn’t interested in modern or contemporary art. His collecting, says Oscar, was rather more “anti-modernist”. As only Humphries could, he once described Conder as an “exquisitely insipid 1890s artist who passionately interested me”.

“I think what he meant was limp, sort of dreamy in a Proustian sense,” Oscar Humphries says. “A whiff of opium to it. And Conder had a friendship with Oscar Wilde, and he has all these other connections. He appears in a poster by Toulouse-Lautrec. The centre of Dad’s library is Oscar Wilde – he has an important collection of Wilde books and manuscripts and letters. The sentimental heart of the collection is London in 1890, in terms of writers and artists.”

Another artist of Wilde’s circle was Aubrey Beardsley, who produced notorious illustrations for Wilde’s symbolist play, Salome. Oscar recalls visiting with his father in 2020 a Beardsley exhibition, to which Humphries had loaned some works, and arriving at Tate Britain before opening hours for a private view.

Other works in Humphries’ collection include a painting by Tamara de Lempicka, drawings by Gustav Klimt, and symbolist works of nightmarish scenes – “Spooky”, Oscar calls them, employing an Ednaism – by Jan Frans de Boever and Alfred Kubin.

“He gave me a beautiful work on paper not that long ago – a gouache by an artist called Hans Bellmer of a woman bending down, and it’s a slight optical illusion: it’s also a huge erect penis,” Oscar says. “A masterpiece of Bellmer. And such a strange thing to be given by your dad.

“Collectors are always jealous. I have a beautiful Balthus drawing that he loved. Every time, he’d say, ‘I hope you haven’t had to sell it yet’. I’ve still got it.”

Periods of financial stress or divorce – Humphries was married four times – cost him works from his collection. Oscar’s mother, Diane Millstead, sold a painting by Edward Burne-Jones, The Mirror of Venus, to Andrew Lloyd Webber, one of the great collectors of Pre-Raphaelite art.

Another painting Humphries once owned by Christian Schad, Zwei Madche, or Two Women – “this amazing 1920s lesbian double-portrait” – is now in Ronald Lauer’s collection at the Neue Galerie in New York.

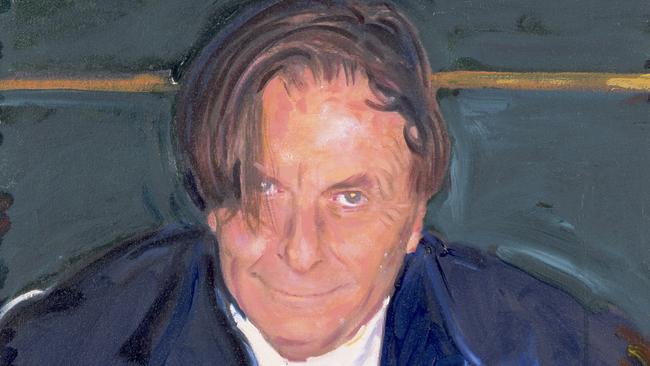

Humphries enjoyed close friendships with artists including Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, John Olsen, David Hockney, Tim Storrier and Margaret Olley – who used the balcony of his Sydney apartment to paint views of the harbour. His portrait was painted several times by artist friends, in character and not, by John Brack, Clifton Pugh, Louise Hearman, Bill Leak, Storrier and Hockney.

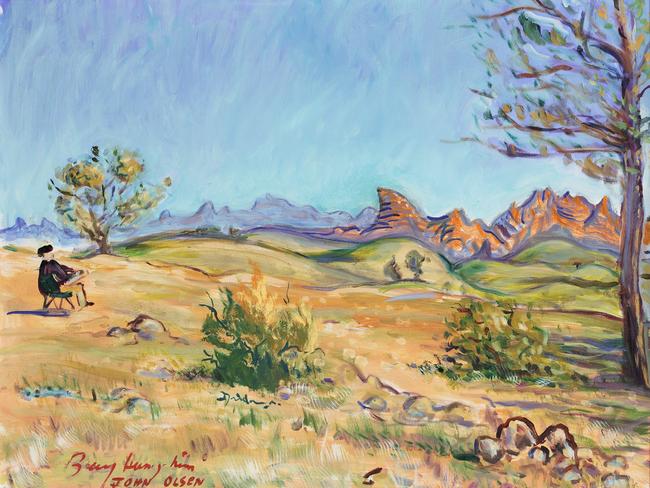

He also enjoyed painting landscapes, and went on art expeditions with John Olsen to the Flinders Ranges. Humphries had intended to give the eulogy at Olsen’s funeral, but died less than two weeks after his great friend.

Was Humphries a good artist?

“He took such joy in it, and when someone takes joy in something, it’s in the work somehow,” Oscar says. “He did paint paintings that he himself would never have collected. I used to tell him that, and he’d sort of glare at me.

“He also was a very good caricaturist – he’d do self-portraits, drawings of people in cafes, funny-looking people, funny drawings of (wife) Lizzie and (son) Rupert and me. They’re very good.”

They came from the same comic sensibility as his larger-than-life personas, Dame Edna and Sir Les. “They are making people look slightly ridiculous,” Oscar says. “And he caricatured types – they are recognisable as a type of person: the unhappy couple, the bulbous-nosed old man.”

The provenance of an artwork or a collection – who owned it, and when, and how and why it passed to the next owner – becomes an important part of its history.

Oscar says it’s too soon for him to discuss the future of his father’s vast collection of art and books. Humphries in his lifetime donated costumes he wore as Dame Edna and Sir Les to the Australian Performing Arts Collection at Arts Centre Melbourne. It’s not known whether he planned similarly to leave his art and books to an institutional collector.

“I don’t want to talk about that – it’s like he’s still here,” Humphries says. “So the idea of dismantling something so intimate to him is … too early to think about.”

He adds: “I’d love the idea of a museum doing a show on some of the collection. I think that would be really interesting.”

As a curator, Oscar has co-produced an outdoor exhibition of sculptures by Damien Hirst in St Moritz, Switzerland, and curated another show of Sean Scully paintings and sculptures at Luis Barragan’s Cuadra San Cristobal estate near Mexico City. Earlier this year he organised an exhibition around writer Bruce Chatwin’s mania for collecting. The exhibition presented an “idea of Chatwin’s apartment”, and included a painting by Howard Hodgkin, a Huari feather hanging, and a Celtic stone head.

“I just did this exhibition in London about Bruce Chatwin … and I was talking to Dad about it,” Humphries says. “He said, ‘I have dozens of letters written to me by Bruce Chatwin’, which I didn’t know. I didn’t know about this connection between the two of them, and I haven’t read the letters.”

Oscar says that not only has he lost his father, but also a bank of knowledge about art and the discernment of his refined taste.

“Independent from a father-son relationship, it’s so sad when great men and women of an earlier generation pass, because when they go, they take so much knowledge with them – so much is forgotten when they pass,” he says.

“What makes him extraordinary, if you step back, is that he had a serious mind and was hugely sophisticated and knowledgeable in so many areas. But he was also a popular star. So on one level he could edit a book of esoteric poems, and on another he had the biggest talk show of the 80s in England.

“I realise how lucky I was to have such a powerful relationship with him, and got to spend so much time with him.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout