‘Barry Humphries loved owing me money — he thought it was hilarious’

He’s been a confidant of Australia’s finest painters – and their dealer – for 50 years. No wonder Philip Bacon’s home is full of treasures.

Philip Bacon stands at the double-door entry of his Brisbane home and it’s clear that his usually calm demeanour has been ever so slightly rattled. The power’s gone off, the car is stuck in the garage, and worst of all, the aircon’s stopped working.

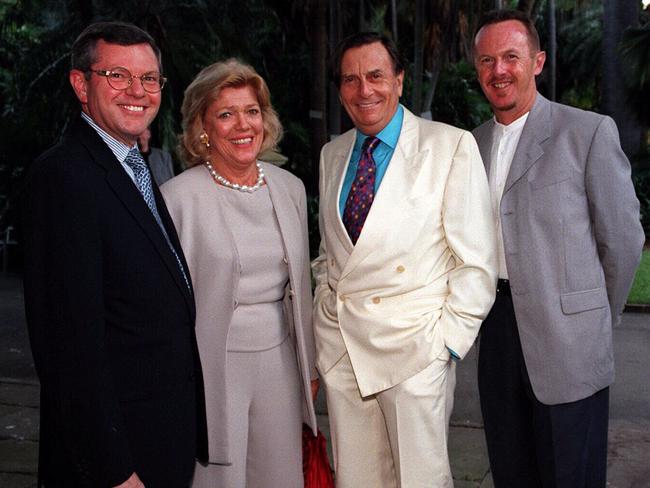

For 50 years Bacon has run one of Australia’s most successful commercial galleries, representing such highly collectible artists as Cressida Campbell, Jeffrey Smart and Fred Williams. Not only that, he’s a substantial donor to the arts, in Brisbane and nationally, having given away, he says, tens of millions of dollars in cash and artworks. He’s the art-whisperer and confidant to some of the nation’s wealthiest and best-known people. He’s also the executor of his late friend Barry Humphries’ estate, which is why this usually private figure was on national television in December, delivering a speech at Humphries’ memorial service at the Sydney Opera House.

Eminently capable, and trusted implicitly, Bacon arranges his affairs to be as quiet, comfortable and wrinkle-free as possible. Of course, he’s as prone to human passions as the rest of us, but even his rare expletives have an air of old-boy gentility.

“I can’t believe the f..king power’s gone off,” he says by way of greeting.

While an attendant from his gallery looks at the fuse box, Bacon ushers me inside. The heat of the summer morning has not yet penetrated the house. Inside it is pleasantly cool and dim. Through the French windows is a distant view of the city skyline, shimmering in the heat.

Bacon built the house, a kind of postmodern Palladian villa, in the mid-1980s, essentially to display his private art collection. That’s what we’re here to see. The entry hall has a barrel-vaulted ceiling, azure blue and with painted white clouds. On the wall beneath is a large oil painting, Passage of Light from the Sea at Numinbah – one of William Robinson’s sublime, almost mystical landscapes of the Gold Coast hinterland. Seen in the half-light, the patches of sky in the painting seem to reach up to the decorative heaven above.

The power at last comes back on and Bacon is in the kitchen, microwaving the takeaway coffees he’d bought earlier this morning on his way back from the gym. Bacon is 76, but with his trim build and pressed button-down shirt, he could pass for a decade younger. One measure of his personal brand is his consistency: he seems never to change.

He was 27 in 1974 when he opened Philip Bacon Galleries at 2 Arthur Street, Fortitude Valley. A former tile factory, he rebuilt it as a multi-level gallery with an annual program of exhibitions and an enviable stock room. He’d borrowed $20,000 from a friend to get started, and when he needed cash again a few years later he was obliged to sell one of the first pictures he’d bought for himself, an Arthur Streeton watercolour of Venice.

“I had a few good paintings and I sold them to keep the gallery running,” he says. “It proved to me that buying art was a good thing, because I was able to sell them for a profit. But the pictures here” – he means his personal collection in the rooms beyond – “I very rarely sell. The few that I have [sold], I regret. I remember them all.”

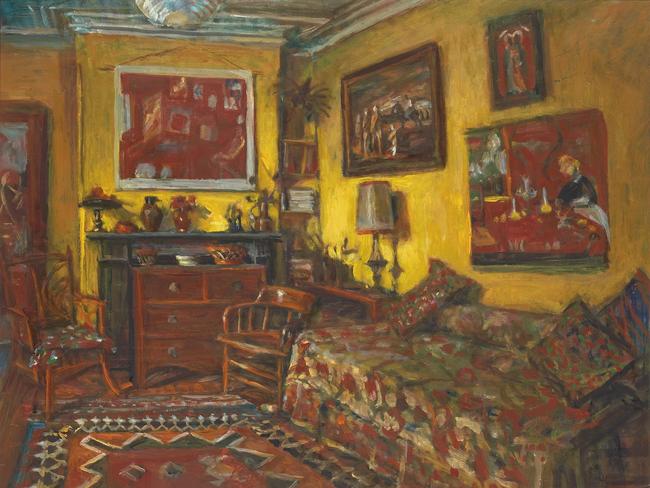

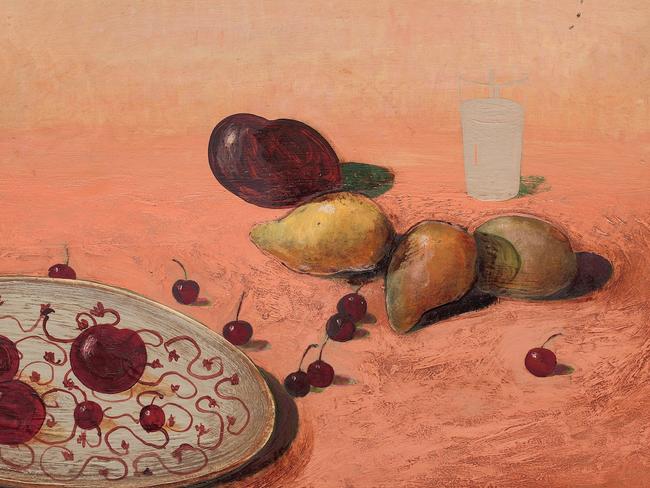

Bacon is sitting at the kitchen table, fidgeting with the edge of a linen place mat. Dominating the room is a large self-portrait by Ben Quilty – a rather overbearing presence at breakfast, one would think, with its thick impasto and bruised flesh tones. There are also two paintings by Margaret Olley: an interior of her home in Sydney’s Paddington, and a still life of pomegranates. Olley, who died in 2011, was a close friend and mentor to Bacon and to Quilty, who won the Archibald Prize with a portrait of her. Bacon continues to look after Olley’s estate, judiciously dispensing funds as donations and keeping inferior or unfinished pictures off the market.

What do art dealers actually do? The answer would seem self-evident, but Bacon responds in his characteristic, unvarnished way.

“We are commission agents, really,” he says. “But different to a real estate agent, fortunately, or a motor-car dealer. There are similarities. We get a product and sell it to somebody and keep a percentage – in my case a very small percentage; other galleries, lots.”

Bacon’s commission can range from 20 per cent to 40 per cent; the higher rate usually is for artists yet to establish themselves in the market.

“You are not selling a Mercedes,” he continues. “The difference is that the artist is a living person with dreams and aspirations, and ambitions and failures. I’ve seen a lot of gallery owners who want to live vicariously through their artists. I’m not a frustrated artist. I’m just interested in art and the business of it.”

Sophie Gannon, director of Sophie Gannon Gallery in Melbourne, says Bacon has “an unbelievably loyal client base from all around Australia and overseas”. She met him in 2003 when her uncle, producer Ben Gannon, was opening The Boy From Oz on Broadway with Hugh Jackman. They all travelled to New York for the premiere, and soon after returning Bacon hired her to be his gallery manager. “Philip taught me the importance of looking after your customers,” she says. “It’s a commercial gallery – you have to work to make sales. That sounds a bit crass. What I mean is, when clients come in, you say hello… He has old-fashioned manners, basics that are sometimes forgotten in some of the contemporary art spaces.”

It may be that Bacon inherited his aptitude for sales from his father, Jack. Philip, the eldest boy, was born in Melbourne and the family moved to Brisbane in the early 1960s when he was a teenager – partly for his father’s business interests, partly for his mother’s health. Jack, a returned Navy serviceman, for a time ran a Barry & Roberts department store, and had success with electrical stores at the beginning of the TV era. Jack died in 1969 at age 50, when Philip was still a young man. He never saw his son open his own gallery. Joan, Philip’s mother, helped out in the gallery until the early 1990s.

“People really liked him,” Bacon says of his father. “My father was quite determined about how he looked. He was always very well turned out. You had to have shiny shoes. He taught me how to iron.”

Bacon’s house is indeed like a private art gallery – not overstuffed, but having an aura of cultivated taste and comfortable living. In the entry hall and adjoining dining room is a Jeffrey Smart painting, Off Brindisi, depicting the open, windswept deck of a ferry. Smart’s paintings typically are classically balanced compositions, but here the scene is deliberately off the horizontal – as if the viewer is being tossed to and fro on the stormy Adriatic.

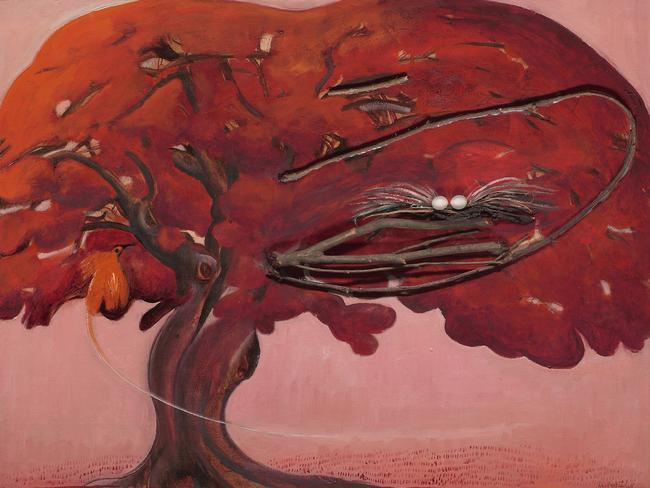

Nearby is a Fred Williams landscape, a Justin O’Brien religious painting and, over the dining table, a large Lawrence Daws painting of waterlilies. A Brett Whiteley picture, Flame Tree and Fruit Dove, 1987, is a mixed-media work which on closer inspection is nested with real twigs and dove eggs.

Some of these works and others from Bacon’s home, about 20 in all, will be on display at Philip Bacon Galleries from February 13 to March 9 in a celebration of his half-century in the business. It will be a rare chance for visitors to see paintings from Bacon’s private collection.

Bacon leads a tour of the house. The living room, with parquet floors and antiques, has a large painting by Rupert Bunny called Madame Sadayakko as Kesa, and a frieze of a medieval pageant by Georges Clairin. In his bedroom are paintings by Ian Fairweather and Grace Cossington-Smith. He has a serene landscape by Lloyd Rees hanging above the bed, and a rather more startling Arthur Boyd picture, Winged Figure, to shock him awake in the morning. It’s unusual to see so many museum-grade paintings in the one home.

“Have a look in the powder room,” Bacon says. Inside, there’s a tiny framed picture of a face in profile, wearing a worried expression. Bacon wants me to see it – not because it is in the exhibition, but for what it says about the eye of one his most treasured clients. Barry Humphries was not only a supreme comedian but also an artist and a serious and knowledgeable collector.

Bacon is not above gossip and name-dropping, but as a rule he is extremely circumspect about discussing his clients, what they buy and how much they spend. Transactions done behind the heavy glass doors of Philip Bacon Galleries stay there. He seems to loosen up when discussing Humphries, though, and perhaps it’s an indication of the closeness of their friendship that he instinctively knows the line that won’t be crossed. As he tells it, Humphries was visiting his home one day, and when he went to the bathroom he was able to name with certainty the creator of that little framed portrait – an obscure Viennese artist, Bertold Loeffler. Not many would have picked up on that.

Humphries had an unusual business relationship with Bacon, being both an artist who showed his landscapes at Philip Bacon Galleries – holiday paintings, as Bacon tactfully describes them – and also a customer. Humphries had the world’s largest collection of Charles Conder’s work, and Bacon occasionally would buy pieces on his behalf. The comedian took a perverse pleasure in being in debt to his art dealer. “He loved owing me money,” Bacon says. “He thought it was hilarious.”

Humphries belonged to the class of collector – connoisseur, really – who knows their own taste and what they want. “You would never sell Barry anything – Barry would buy something,” Bacon says. “He would say, ‘Oh, I quite like that’. You could never say, ‘Now Mr Humphries, have I got a deal for you’. Over the years I would have sold thousands, maybe tens of thousands of pictures. And there is always somebody coming along who has a great eye, and wants to make a collection.”

Bacon leads me to the painting he prizes most, the Rupert Bunny portrait of Madame Sadayakko, dated 1907. Sadayakko was a famous actor at the turn of the last century – a kind of Japanese Sarah Bernhardt – who may have been an inspiration for Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly. This beautiful picture is probably best seen in the evening or by lamplight, not in the strong daylight reflected from outside. Sadayakko is shown full-length from behind, her face hidden, and wearing a silk gown the colour of celadon glaze. Behind her is a glowing lantern, like the rising moon.

Bacon loves the painting’s mystery – the fact that Bunny has depicted Sadayakko turning away from the viewer. Is she preparing to go on stage, or is she weeping? He bought it at auction for $77,000 – “an absolute bargain” – from a finance company that was offloading its corporate collection during the early-1990s recession. It would be worth considerably more today.

“People say, ‘What would you run out the door with?’” he says. “Well, everything – if I could carry it, I would.”

Bacon is interested in art for the pleasure it gives. His personal taste – reflected in his private collection and in his stockroom – is for landscapes, still life and figure paintings by blue-chip, established artists. Buyers interested in Aboriginal art, or avant-garde conceptual art, wouldn’t be making Philip Bacon Galleries their first port of call.

He has no time for dealers who promise buyers a return on investment – a market encouraged by superannuation laws that allow artworks as assets as long as they are kept in secure storage, unseen and unenjoyed. But he’s also a businessman, and quietly asserts an “implicit guarantee” that the paintings he sells are of such quality that they will at least hold their value, should the owner decide to sell.

“I think of it as a long-distance race,” he says. “If I’m confident enough about an artist to take them on, then I’m also confident – as much as I can be – that their values will hold.”

An exhibition at Bacon’s gallery, to be held concurrently with the show from his own collection, is from three private collectors who have died, or are downsizing. There’s a large number of works by William Robinson, some Fred Williams landscapes, and a single-owner collection of paintings by Sam Fullbrook.

A growing part of his business is deceased estates, as children sell paintings that once belonged in the family home. Many no doubt will find their way to other collectors who will love them, or even to public galleries. But younger generations do not necessarily want to live with old-school pictures – the same way they don’t want their parents’ brown furniture or silverware. The quality of an artwork may not change, but fashions do, and it’s sobering to think what may happen to private collections – Bacon’s and others’ – when the generational transfer of wealth is complete.

Philip Bacon Galleries in Fortitude Valley is like a carpeted oasis after the baking footpath outside. The surroundings are cool and unfrazzled – a bit like the owner himself. At the entry is a 16th-century Indian sculpture of Kubera, the god of wealth, that is missing its head. It could almost be a symbol for Bacon’s manner of dealing with his clients – not decapitation, but his utter discretion about their financial interests and privacy.

On the walls is a show by William Mackinnon, a Melbourne artist Bacon has recently taken on. His edgy landscape paintings of wrecked cars on outback roads and suburban houses are done in acrylic, oil and automotive enamel – one has been purchased by the National Gallery of Australia. The NGA also acquired from Bacon one of Cressida Campbell’s exquisite woodblocks, Bedroom Nocturne, for its retrospective of Campbell’s career in 2022. It raises the knotty question of conflict of interest: regardless of the quality of the art work, Bacon is a dealer who also sits on the NGA Foundation board. He says he is never involved in decisions about institutional acquisitions of work by artists he represents.

A manager looks after the day-to-day gallery business, as Bacon’s interests are considerably larger than selling paintings. His office is just inside the gallery entry. At his desk he fans through a thick sheaf of papers – the posthumous affairs of one of his artists. A lot of his work is involved with administering the estates of artists he has represented, including Margaret Olley, Jeffrey Smart and Barry Humphries.

Bacon’s philanthropic activity also keeps him busy. It’s rare to attend a major exhibition or performing arts event – such as the Brisbane Ring Cycle last December – and not find him named as a supporter. In 2019 he was named philanthropist of the year by Philanthropy Australia. And he is a veteran non-executive director, currently sitting on the boards of the Brisbane Festival and the Bundanon Trust, as well as the QAGOMA Foundation. “When Philip’s in, he’s all in,” says Rupert Myer, another high-profile patron and chairman of arts boards. “It’s never solemn duty – he gets such delight from it.”

Evidently Bacon, who does not have children, likes to be occupied, and sometimes to keep to himself. Cressida Campbell has had exhibitions with him for more than 30 years, but she often doesn’t know and has to ask where he’s going to spend Christmas. (He’s just been to India.) “Like many people, I don’t think Christmas is his favourite time of year,” she says. “He’s always on planes, going to board meetings and God knows what. He loves making decisions and talking to people and finding out what they are interested in.”

The exhibitions Bacon is holding this month will mark his golden anniversary in business, but he has avoided other public displays of affection. Louise Bezzina, artistic director of the Brisbane Festival, was planning to organise a celebration for him – but he didn’t want a fuss made.

Another form of recognition may be more appropriate for the art dealer. Lyn Williams, widow of Fred Williams, wants Bacon to have the last show of Williams’ landscapes from his estate, as a token of her respect for him. The paintings from Williams’ Pilbara series – his final body of work, completed before his death in 1982 – are likely to generate considerable interest when they are shown at the gallery in July.

Strangely, given Bacon’s close involvement with artists’ estates and philanthropy, his own end-of-life plans are a bit up in the air – although he has no intention of going anywhere soon. You can hear Margaret Olley’s voice when he says, in breathy imitation of her, “What’s it all about darling?” It’s not so much a question as an injunction to live your best life while you can.

The man who has already donated millions of dollars to the arts prefers to give his money away while he’s alive. He is distrustful of the way large institutions handle bequests, and he hasn’t set up a foundation or a trust, so Bacon’s philanthropy will probably end when he does. There’s no plan of succession where his affairs will be managed after his death, in the way he manages Olley’s and Humphries’ estates.

“There’s nobody really like me in my life who can do it,” he says matter-of-factly.

As for the paintings in his private collection, he hasn’t decided which, if any, will go to a public gallery. So this month may be an opportune time to inspect his remarkable collection, best seen when the power’s on. b