Why my migrant parents Helen and Otto Lang loved Anzac Day

Helen and Otto Lang found safe haven in Australia. They expressed their gratitude with a passionate commitment to Anzac Day and a recipe for ‘Flemingtons’ – after mishearing ‘Lamingtons’.

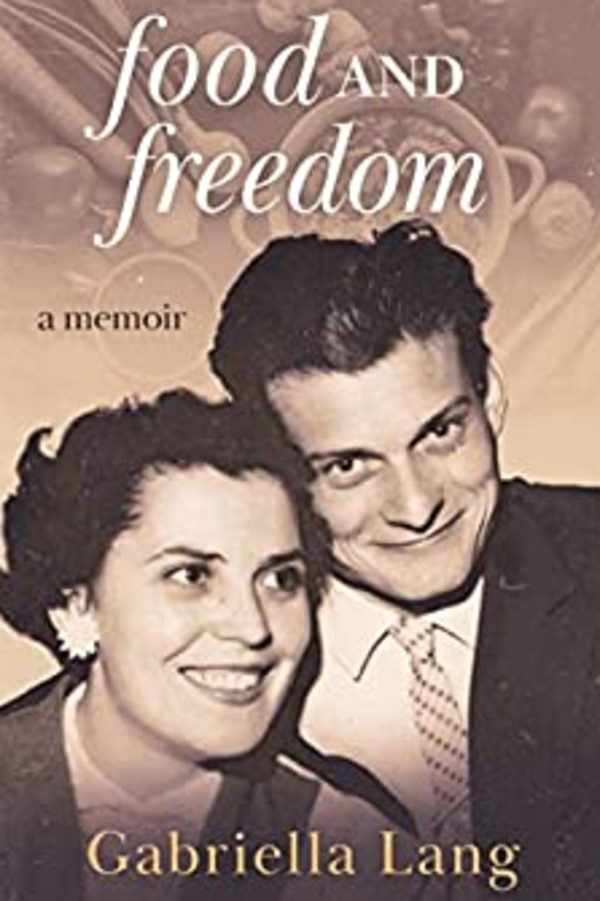

My parents, Helen and Otto Lang, escaped from Hungary in November 1956. A newly married young couple, they were caught up in the desperate exodus of mainly young professional people who voted with their feet when the Russian tanks rolled into Hungary and the killing spree began.

Like most of those brave refugees, my mother and father had no choice but to walk through the countryside to the Austrian border. As a child, I never appreciated how terrifying an ordeal this must have been and it is only now that I look back with a mixture of incredulity and great admiration.

They walked for 60km, across muddy frozen fields at night, while by day they hid in undergrowth from the patrolling Russian troops who had orders to shoot on sight. Every step took them further away from family, friends and the life they knew. Somehow after three gruelling days, they made it to the border.

After three desolate months in a refugee camp in Melk in Austria, my parents arrived in Sydney – a place so completely alien to them that they felt they had been transported to another planet.

Hand in hand, they looked around nervously and waited to see if the natives were friendly. They were. Friendly, welcoming and warm. Australia took the young couple into their hearts and in return, my parents came to passionately love their new homeland.

Had Australia ever been threatened by a foreign aggressor, I feel sure that my father would have taken up arms in defence of his adopted country. And done it well – in his youth, he had been a crack rifle shot.

And my mother would no doubt have volunteered for the catering corps, thus contributing significantly to the quantity and even more to the quality of the food.

Fortunately, it never came to this. But every year, my mother took great delight in honouring Australia’s armed forces on ANZAC Day. Without fail, every 24th of April, out came the Australian flag from its home under the stairs. My mother inspected it carefully and when it passed muster, she instructed my father to erect the flagpole in the front garden ready for the flag to fly proudly all the next day.

As everyone knows, rain on ANZAC Day is as much part of tradition as floppy digger hats. As is the game my mother insisted on calling Up Two! My parents would also often wake at 4am and attend the Dawn Service in Manly. As soon as they got home, up went the flag, on went the television and down went my mother – onto the couch where she stayed and watched the ANZAC Day March. The entire March. Fuelled by cups of coffee and various snacks, she sat through all four hours and became so familiar with many of the marchers year after year that if someone distinctive was missing, she noticed.

“The man with the crutch and funny ears isn’t here this year. Poor thing. I hope he is OK.”

One year – I think I was 16, and driven to despair with embarrassment, since my mother had managed to get her hands on a flag so big you could hear it flapping outside – I sat down beside my mother, to watch the ex-Diggers parade past.

I politely pointed out that it was not outside the realms of possibility that some of those ageing soldiers, whom she was cheering so enthusiastically, had been shooting at Hungarians during the Second World War. At her father or uncles possibly.

“We were on opposing sides, you know,” I added helpfully, really trying to drive the point home.

My mother turned and glared at me. She was silent for as long as it took for me to feel ashamed of myself – which I blush to admit, was longer than it should have been. Then she said quietly, “It doesn’t matter. They were young. And brave. And they fought for their country.”

My father – while every bit as patriotic – was more pragmatic. When I asked him one year why he attended the Dawn Service, he smiled his slow smile and said: “Hungarians are used to celebrating spectacularly disastrous military operations!”

My mother’s ANZAC Day commemoration also included baking not the traditional Anzac biscuit, but small cakes she called “Flemingtons”. To most people they looked a lot like lamingtons, but when my mother was first introduced to this Aussie icon soon after her arrival here, she thought they bore the name of the Sydney suburb. By the time she discovered her mistake, the name had stuck.

Having rechristened the delicacy, she improved it. My mother’s Flemingtons contained two layers of vanilla sponge, joined together with strawberry jam, rolled in a double layer of dark chocolate and toasted coconut.

I have no idea if it was any one of these innovations that lifted her cake from the delicious to the sublime or a combination of them all but they were mouth-watering. And meant for sharing. So, every April 24 between flag inspecting and flagpole erecting, my mother found time to bake tray after tray. She arranged these on six special plates (only ever used on this day, they featured cringe-inducing paintings of Australian flora and fauna) and distributed them to the neighbours, who had all been eagerly anticipating this treat since early morning.

Every local cook asked for the recipe and many tried to replicate it but somehow, their efforts were never quite as good as hers, for my mother was an excellent cook. She lived and breathed the idea that food is love, although she didn’t have to actually love someone to feed them. No problem was too great that several pieces of cake, biscuit or slice would not make it better. Sometimes, if you ate enough, the problem went away altogether.

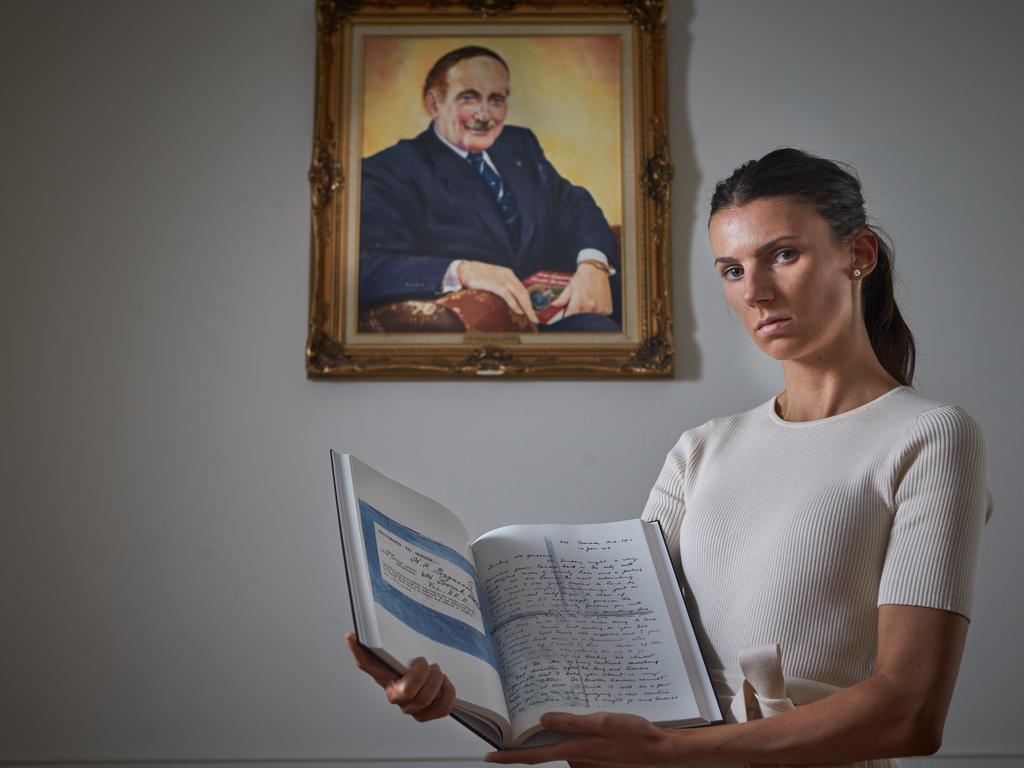

It was only after she died that I realised that I had hardly known her. As a child, I was too busy trying to work out who I was becoming to care who she was. After my daughter was born and my relationship with my mother improved dramatically, my perception of her was still as my mother and an adored grandmother.

I saw her not for who she was, but who I was in relation to her.

Then she died. I found her letters and notebooks and gradually, I began to get some glimpse of the real her – who she had once been, who she had ultimately become.

The mother I thought I knew had been practical, organised, not given to sentiment. She was different in her diary. She wrote about her love for my father, to whom she was married for more than 50 years. She wrote about the agonising decision she made to leave her old life behind and how – even after decades in Australia – her Hungarian homeland still tugged at her.

Looking out at cockatoos in her Sydney garden one day before she died, she wrote: “This is the choice I made then. This is the choice I would make again. But it breaks my heart …”

I baked my first batch of Flemingtons on ANZAC Day a month after my mother died. I carefully placed them on two plates decorated with kangaroos and koalas. Then – without really intending to – I sat down and watched the Anzac Day March. And I cried. For those brave old Diggers. For the loss of young lives in so many conflicts. But most of all, for that dear woman who had taken such a truly Australian celebration and made it her very own.

This is an edited extract from Food and Freedom by Gabriella Lang. The book is a self-published a memoir of her parents’ life in Australia after fleeing Hungary, available now.

Flemingtons recipe

Ingredients:

1 square or rectangular vanilla sponge cake, at least one day old. Fresh cake will disintegrate into a gooey mess so don’t even bother.

4 cups icing sugar – very well sifted

5 tablespoons Dutch cocoa

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons boiling water

3 cups shredded coconut

Strawberry jam

Method:

Cut cake into equal size cubes. Then cut each piece in half (so it can be filled with jam). Freeze for at last an hour – 90 minutes if possible.

Spread each half piece with strawberry jam. Sandwich together.

Meanwhile, make the chocolate icing. Melt half the butter in a saucepan. Add half the cocoa and half the icing sugar. Stir until smooth. Add tablespoon or so of boiling water if needed. It should be thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

Carefully dip each cube of cake in melted chocolate until completely covered. Put back in freezer again for at least 30 minutes.

Meanwhile, toast the coconut on a large tray in the oven. On 170C. Should take about 10 minutes but be careful – it can burn easily. Cool.

Make the rest of the chocolate icing as before.

Dip each cube of cake again into the melted chocolate and immediately into the toasted, cooled coconut. Press coconut onto surface to make sure you get a good covering.

Refrigerate – not freeze – for at least 30 minutes.

Take out of refrigerator at least 30 minutes before serving.

Can be served with whipped cream. And best eaten while watching the ANZAC Day March.