War diary of World War One veteran Les McKay is great-niece’s pride and joy

A chance discovery of her great uncle’s battered war diary opened Annette Exon’s eyes to what the first ANZAC generation endured.

Like so many men of his generation, Les McKay never spoke to his family about the Great War. They accepted that what he did and experienced on the Western Front had stayed there, the memories buried deep, too raw ever to be shared.

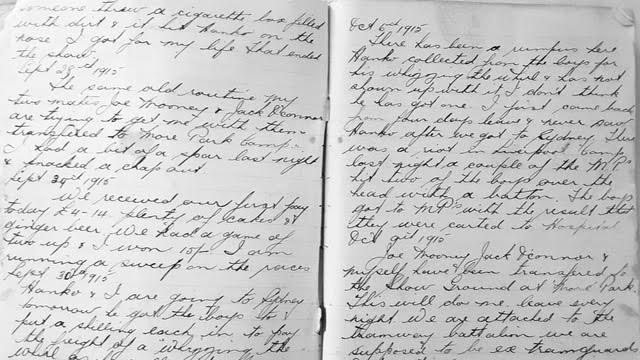

There was, however, one place where he could confide the fear, frustration, horror and gallows humour of life in the trenches – his diary.

And unlike so many other young Australian soldiers, Corporal McKay lived to come of age and come home from World War I. But it wasn’t until his great-niece, Annette Exon, 64, chanced across the battered journal in her late mother’s keepsakes last year that she understood – really understood – the bloody crucible that made her mysterious Uncle Les the man he became.

Through these dog-eared pages, filled with his cursive handwriting, he tells the story of how a starry-eyed 17-year-old joined up underage in September 1915 and survived everything the Germans threw at him in the killing fields of France and Belgium.

By the autumn of 1918, near the war’s end, he was the grizzled veteran who had endured too many close calls to count while engaged in one of the most dangerous jobs going as a combat engineer: digging trenches, saps and laying duckboards in the cloying mud for the infantry, yet far more exposed to enemy fire than a regular soldier.

He was in the thick of it after the Australians’ brutal introduction to warfare on the Western Front at Fromelles in July 1916 where 5500 Diggers were killed or wounded in a single harrowing day, and went on to see more action in the unspooling Somme campaign, the charnel house of Passchendaele in 1917, and the helter skelter pursuit of a retreating German army in the culminating months of the war.

On October 1, 1918, barely five weeks out from the Armistice, he wrote nonchalantly: “I got a bit of a knock today. A piece of shrapnel skinned the top of my right hand. It is only the skin off and too trivial to report.”

McKay was a walking, laconic-talking contradiction in his immaculately wound leg puttees – the envy of the entire company, he claimed during training – while entertaining a rouseabout’s indifference to military discipline.

Away from the front, he was constantly in strife with one officer or another. Sentenced to seven days in the lockup for being absent without leave, he was slapped with a further charge of insubordination for smiling through the disciplinary hearing. But couldn’t he handle himself in a fight. Whether McKay was using his fists in a regimental boxing tournament or paving the way to “hop the bags” in an attack, he was utterly dependable when it mattered most to his mates. There was no trace of the inveterate larrikin under fire.

Reading his war diary, Exon found herself lost in admiration for a man she never knew. “I didn’t have much interest in war and that kind of thing,” the retired Qantas flight attendant says from her home in Brisbane. “So I was really surprised by how deeply I got into the diary. Once I started it, I couldn’t put it down.”

What happened to Les after the war? Nobody really knows, Exon says, her voice tinged with sadness. He made quite a splash on the prize-boxing circuit and then set up a successful plastering business in Sydney. For a while, he lived in a neat terrace in a well-to-do pocket of Waverley, not far from Bondi Beach.

But he increasingly cut a solitary figure and drifted away from the family. Her mum, Betty, lost touch with him and the faded photograph of the smiling young man in his AIF uniform was like a ghost on the mantelpiece for Exon when she was growing up.

“I knew I had an uncle Les and he had been in the war and he was important enough to my parents that they made Lesley my second given name,” she remembers. “But that was about as far as it went … the war wasn’t something we ever really discussed. I mean, Dad served in New Guinea in World War II, and he didn’t talk much about that, either.”

So as the nation prepares to mark Anzac Day, it’s time to let Corporal Leslie James McKay of 15th Field Engineers, Australian Imperial Force, speak for himself:

September 17, 1915

I have enlisted for the war … We haven’t been issued with uniforms yet. We wear dungarees. We went on squad drill today and it is pretty crook and in the boiling hot sun all day with a sergeant bellowing at us.

January 20, 1916

I have just a minute. We have embarked on S.S. Runic and are now lying out at midstream. It was pouring rain when we left. Everyone was crying including myself. Clara was heartbroken as was my mother. I feel very depressed.

August 15, 1916

My first intro into the frontline today. We are at Fleurbaix, Armentieres is on our left.

September 6, 1916

Ten of us were woken up at four this morning and ordered to go to the frontline and collect every pick and shovel we could see. It was teeming with rain and bitterly cold … the Pioneers were out in No Man’s Land burying the dead Aussies. I sneaked over to see what I could find when a very unreasonable Fritzy started sweeping with a machine gun. I lay down flat for half an hour before I crawled back realising I had more pressing business elsewhere. There were dead Aussies everywhere.

September 30, 1916

A shell burst almost on top of me today but I’m still here. It is raining all the time. Just slime and slush. It’s no good trying to keep dry. We have to put our wet clothes on in the morning.

October 11, 1916

Casualties have been very heavy. I wonder if the people back home know of them. A lot of my old Christchurch pals have been killed. Fritzy gave the frontline something today with minenwerfers. They are terrible things … one went clean through six feet of sandbags, two courses of iron, three feet of concrete and blew a dugout and the occupants to smithereens. We were crouching against the parapet when one came right at us. We all had the one thought – goodbye. It’s no good running so we waited. Over it came, screeching right on top of us. I closed my eyes and thought for a minute I was in Turkey or heaven or wherever you go, but everything was right. It landed at our feet – a dud. We looked at one another, smiled a silly smile.

October 19, 1916

Up at 9.30. Only a few miles from the Somme now. They took the conscription vote today. With few exceptions the Coy (company) voted ‘No Conscription’. I was refused a vote on the grounds that I was too young. When I went in to vote, they asked me what I was going to vote and I said ‘no’ so they knocked me back. But I told them that they didn’t think I was too young to fight.

November 6, 1916

It is a little quieter today. There are a great many dying of exposure. I took an hour to dig one fellow out of the mud. The suction nearly pulled me down. We found many who could not get out so had just lay there and died. That lieutenant … who sentenced me to seven days in Christchurch was in it last night. He filled himself with rum and left his Section to it. He is now under close arrest, charged with cowardice before the enemy. Poor old Scotty McDonald got knocked but not seriously. I had a laugh, I couldn’t help it. He won’t be able to exhibit his wound to anyone.

November 28, 1916

Either side of the track was littered with dead this morning when we arrived. The 32nd Bat was caught going in last night and were cut to pieces. We buried them in the shell holes. One poor fellow died just as we got there. He was lying in a shell hole on his back with his leg blown off … An infantry chap who was covered in mud and slush and looked half dead with the cold was coming out of the line eating a biscuit and eating it with as much relish as one would steak and oysters. His eye caught on an oldish chap. A half-starved, poor miserable looking half-human he looked too. He was just passing us when the chap eating the biscuit stopped him & gave him the biscuit saying: ‘Here you are boy. You need it more than I.’ That’s the stuff the Australians are made of. Caked in mud, shivering and yet always a smile. We got home without a shell.

December 8, 1916

This morning there’s a shell hole, right between our dugout and No. 4 Section exactly on top of where I was sleeping. Twelve of the boys in the No. 4 were knocked. The shell landed nearer to me than anyone else and I never heard it. That makes about 40 casualties up here. Pretty heavy for an engineering Coy.

December 11, 1916

Completely lost my nerve today … I walked no more than three yards when there was a sudden swish, crash and a roar, and where the dugout had been, was a crater bigger than a minenwerfer hole. I wasn’t hit but half buried. It was a clear day. I looked up but there weren’t any planes about so it couldn’t have been a bomb. A shell always warns us by starting a screech until it gets louder and louder. I thought it might have been a premature burst from one of our own guns but they weren’t in action. However, I commenced to work when, crash, up she goes again almost as close as the other. A piece ripped the sole clean from my boot … Lieut(enant) Turner our new officer and a good fellow came along then and reckoned they were bombs but they weren’t. Fritz sent a lot over and we got a dud. They are high velocity shells about 8 inch and painted like a needle. Armour piercing they call them. I don’t care what they call them, but keep them away from me. Fritz gave us hell all day. We have a new Corporal and he has only just landed in France. While we were crouching down I sneaked a look at the Corp. He looked very crook on it. It was an extra heavy day‘s shelling, but later I just mentioned casually to the poor Corp(oral), ‘Fritz usually makes it pretty hot on these fine days but he let us off today.’ He nearly chucked.

January 27, 1917

Nearly got it today. Had just knocked off for dinner when swish, bang! A big shell shaved the dugout. It burst outside and nearly killed us with concussion.

May 21, 1917

I am spending my 20th birthday in bed. I feel very miserable and sick.

September 27, 1917

Oh God this was a terrible day or rather yesterday was. There aren’t many of us left now. About 11 o’clock ‘battle order’ fall in. Most of the boys penned a last hasty note. The very last for a lot. We plodded silently along the duckboard track. It was pitch dark actually but the roars and flashes of the guns made it like day. Shells literally rained on us. Jimmy Gill was the first. He was hit in the side but is still alive. Len Price was next. Lieut Turner then was hit in the leg but he just bound it up and carried on. Will I ever forget it. We could not hear one another speak. An infernal hell on earth. We … waited like this for hours until early morning. We were under gas for three hours without a break. We waited silently for what was coming to us. About 5am hell broke loose. Our guns opened out with a short terrible bombardment and then a whistle blew and over we went. Our job was as soon as a position was taken we had to set up barb wire entanglements, a bonza job. Poor old Bill White went next.

October 9, 1917

Another big day. One shell … nearly killed us with concussion. We were just making up our minds, when someone shouted out through the door, ‘Any stretcher bearers here?’ ‘No’ I said. I poked my head outside. An engineer of the 4th Division was lying outside with a huge hole in his neck. I looked closer and it was one of my old pals, Stan Eade. A stretcher was no good for poor old Stan then. I couldn’t do anything for Stan so Curly, the two Wilsons and I made a run for it.

November 3, 1917

What a place is London. Dave Wetherall of the 4/11th Batt. and a sailor Mick Connelly … off the ‘Australia’, have been having the time of our lives … how we have been celebrating.

September 27, 1918

That dreaded ‘Battle Order’ came through today and here I am in the thick of it again. We took 150 rounds of ammunition and … passed shadowy hurrying figures. They hurry coming out, but walk very slowly going in as we were. Shells were landing pretty handy to us.

September 28, 1918

My word it was cold last night. I nearly froze. We are in a quarry about one mile long and half wide … Fritz is now shelling us very heavily. We are right on the Hindenburg Line and are going over in the morning with the Yanks.

November 9, 1918

I haven’t touched my diary for over a month … My hand was in an awful state, swollen right up to my elbow. I was afraid to report it then. My mates urged me but I didn’t not want to leave the Coy. I stood the pain as long as possible but gave in. I told the doctor that I got kicked playing football on an old sore. They sent me to a dressing station then to Le Havre and the next day to England. We got a great reception and everyone was talking of the Hindenburg Line and if we were among those who pierced it. This is my second trip to England and both times I felt too miserable to talk.

November 11, 1918

Was in my ward today and hearing a lot of cheering. Went out to see what the row was all about. Nothing much, only that the war is over. I suppose they will believe that my hearing is failing me now, and send me home.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout