Anzac Day reflects changing face of the nation

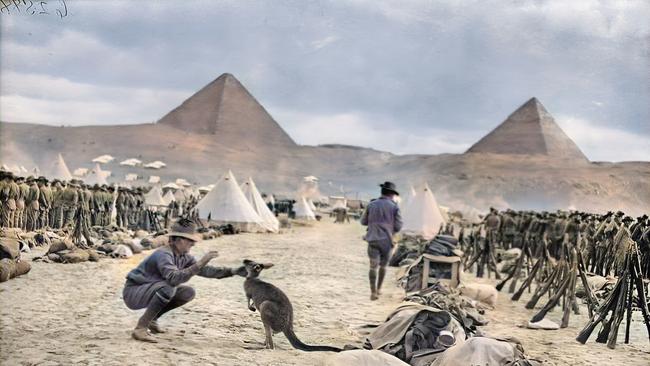

Anzac Day has been a part of Australian life since 1916, when Gallipoli survivors gathered in Egypt to remember lost comrades. It’s since become the day on which Australians (and, of course, New Zealanders) especially remember their dead in many, many wars – too many for such formally young nations. But Anzac Day is changing: as it always has changed.

The Gallipoli veterans (and the many more who were to die on the Western Front) knew the fallen as mates, with whom they had shared the danger of the trenches. As Anzac Day became a day for all Australians (becoming an official day of commemoration through the 1920s), they shared the burden of remembrance more widely – with families, of course, but also with the communities from which they came.

Anzac Day became associated with the very idea of Australian nationhood, even when contested (as it became fifty years after Gallipoli) untainted by the ambiguities of Australia Day, which grimly hangs on as the official national day. But the way they marked the day changed. In the 1930s silent crowds, many remembering dead loved ones, watched huge columns of returned men march through their streets (followed by “the sisters”, who got a special cheer).

By the 1960s, those crowds largely fell away, as an unjust war challenged the simple certainties of king and empire. Many will recall the thin crowds of the 1970s, and the resurgence of attendance in the 1980s, infused by an assertive nationalism that might have taken aback the British-Australians of the old Australian Imperial Force.

Now spectators are rarely tearful relatives. A family history boom has allowed many with no personal memory of war to find an Anzac in the family. The smiling, clapping, flag-waving crowds who are expected to return to post-Covid Anzac Days are very different to the silent, weeping – and much larger – attendances of 80 years ago. And, despite the 100,000 Australians – all ADF regulars – who have served in peacekeeping deployments over 60-odd years, the marchers are few compared to the phalanxes of citizen volunteers, veterans of the world wars.

We can expect some changing trends to accelerate. Indigenous veterans might be especially visible this year, a reminder that they were once not seen, as they now rightly wish to be heard. We will see marchers from what were “allied” forces. We have long clapped the gallant Poles, who had fought for “our” freedom though they lost their own, and the “South” Vietnamese, defiant in defeat. Now, the diversity is growing.

Perhaps the group most apparent are Indian-Australians, the fastest-growing migrant group. Seeking a way to connect with their new nation, they emphasise that Indian mountain batteries landed alongside the Anzacs on April 25, and that Sikhs fought beside Australians in the doomed August offensive. We are also now seeing calls that Anzac Day should embrace all of Australia’s wars, not just those fought overseas, but also the

“Australian Wars” fought for the possession of this continent between 1788 and, say, 1928. They brought the deaths of at least as many Indigenous people as Australia lost in one or another of the world wars.

A coalition of informed and impassioned activists (including me) are urging that the Australian War Memorial honours the commitment made last year by its former director, Brendan Nelson, to recognise frontier conflict, perhaps Australia’s most costly war. A recent poll of Canberra Times readers revealed that 68 per cent favoured the change: the question is now ‘how’, not ‘whether’.

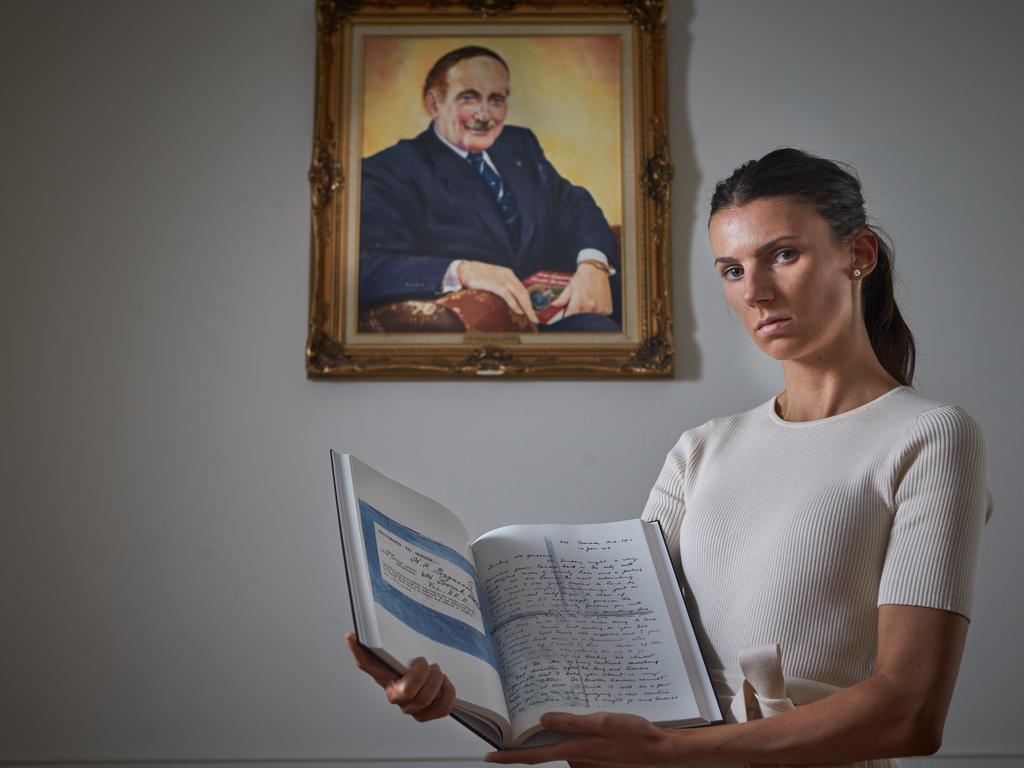

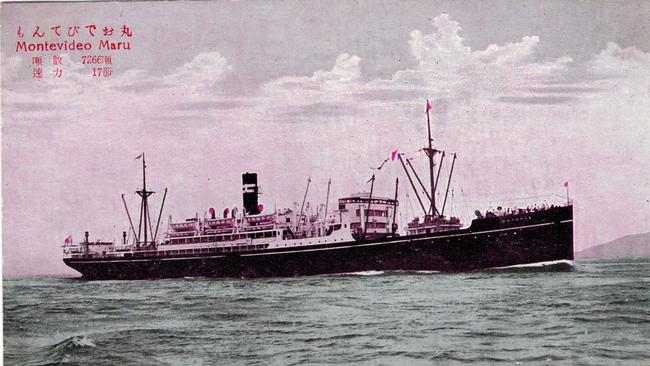

The major story this Anzac Day is that 81 years after it was sunk by a US submarine, the wreck of the Montevideo Maru has been discovered deep in the South China Sea. This, the resting place of more than a thousand mostly Australian prisoners of war and civilian internees, remains Australia’s worst maritime tragedy. Its discovery will in some ways change little: the uniformed members aboard at least have all been commemorated by name on various memorials, while hardly anyone still alive can remember those killed. These civilians (and those killed in, say, the bombing of Darwin) surely deserve to be commemorated on the nation’s Roll of Honour.

The other substantial defence issue Australians are debating – one which also relates to both the South China Sea and American submarines – is the question of whether the AUKUS alliance and its nuclear submarines will make Australia more or (as I believe) less secure. Let’s hope that decisions made by both Scott Morrison and now reaffirmed by Anthony Albanese will not lead to more names on the Roll of Honour. I am pessimistic.

Anzac Day is changing, as it always has; and as it surely always will if it is to retain its relevance as Australia’s de facto national day, a day on which as a people we recognise what war has cost this nation, and how it has changed us.

Peter Stanley is a military historian and former principal historian at the Australian War Memorial