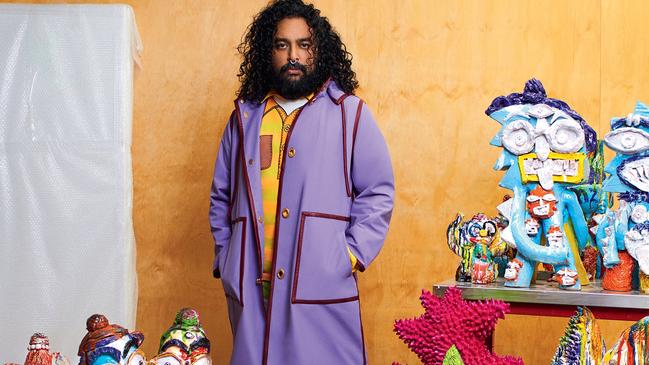

Artist Ramesh Nithiyendran on culture, craft and creativity

When artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran couldn’t see himself reflected in any corner of the art world, he decided to create his own niche.

Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran is a conundrum, in the most marvellous of ways. A first-generation Australian – born in Sri Lanka, he and his family fled the Civil War and migrated to western Sydney when he was a baby – and he is the only artist among his extended family of 40-plus cousins.

His wild, garish, exuberant and, yes, childlike sculptures come from a place of deep thought and academic theory on topics as wide ranging as religious, cultural and social politics, homosexuality, race and gender.

Yet he loves that people love them simply because. He derives equal satisfaction from showing at the prestigious Frieze London contemporary art fair before the art cognoscenti as he does displaying his work to the masses at Vivid Sydney. He is an artist who worships fashion – witness him in The List’s photo shoot rocking his Gucci threads – yet happily greets me at the door of his studio warehouse dressed down in Crocs, shorts and an old Adidas tee.

He is also very hot property right now, a fact that both delights and sits very comfortably with him.

“I don’t mean to blow smoke up my own arse, but my works are very highly sought after,” Nithiyendran says matter of factly. “I never thought I’d be where I am now. I went to Auburn North Primary, a low socio-economic, migrant, refugee school [in western Sydney]. My community would never have imagined that someone in their space would be styled in head-to-toe Gucci for a mainstream publication! But I’m happy to say I’m fairly successful. I think I should own that.”

Indeed. In the past year alone, Nithiyendran has had three major installations and public art commissions: a permanent outdoor public art sculpture commissioned by HOTA (Home of the Arts) on the Gold Coast for the museum’s entrance; a monumental 70 -piece sculptural installation called Avatar Towers that greeted visitors in the vestibule of the Art Gallery of NSW and has now been acquired by the institution; and Earth Deities, an installation that was included in the line-up of Hobart’s subversive arts festival Dark Mofo.

Represented by Sullivan+Strumpf in Australia and Singapore, Nithiyendran was recently picked up by Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai, which sold all 14 of his works before his debut show even opened in January.

See the list: 100 Arts & Culture stars

If it seems as if he’s having a moment, it’s worth pointing out that it’s no coincidence Nithiyendran has achieved the status he has today. His success has come about through a deliberate and calculated analysis of the art scene, establishing how to maximise his opportunity for exposure; slavish hard work; and, it must be said, remarkable talent – even if he does cop the occasional “my child could have done that” jibe (more of which later).

Nithiyendran is undeniably the anomaly in the family. Brought up in modest surrounds (“my parents have the migrant narrative where they’ve now got their own house in Lidcombe with five bedrooms and a dog”), he was an academically driven, high-achieving child who was well behaved and respectful but confounded his parents.

ARTS & CULTURE 100

‘Who will stand up for the arts?’ Ben Quilty

Australia must now recognise the depth of talent in its midst and celebrate a new generation of cultural leaders.

Shape shifter and a captivating artist

When artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran couldn’t see himself reflected in any corner of the art world, he decided to create his own niche.

The kid’s all right: a stellar rapper stays grounded

At 18, Australian rapper The Kid Laroi is a global superstar in his field. So where did he come from, and where to next?

Chain reaction as artists ride the crypto wave

From Arnhem Land to capital cities, artists are embracing technology in new and inventive ways. But does digital art live up to the hype and hefty price tags?

What’s the point of art?

What’s the point of art? Perhaps Jackson Pollock said it best: ‘Art is coming face to face with yourself.’

How Baker Boy took hip-hop across the divide

As homegrown hip-hop has gained traction, standout Indigenous performer Baker Boy is about unifying black and white Australia.

What celebrated novelist Hannah Kent did next

Acclaimed South Australian novelist Hannah Kent explains why her creative leap into screenwriting was so nerve-wracking.

Aussiewood draws on a deep talent pool

There’s a story behind Aussiewood and why our homegrown stars and local industry play well on screens big and small around the world.

Star turn: from bricklayer’s son to principal artist

Prodded into taking dance lessons at an early age, Callum Linnane tapped into the passion that has elevated him to the ranks of ballet’s most exciting performers.

Arts rainmakers see more ways to source funds

Arts philanthropy has embraced the digital age, with the constraints of the pandemic spawning new schemes to buttress the cultural bottom line.

Out of the wings comes a strong, diverse cast

Asian-Australians make up a fair portion of our population and that fact is finally being reflected on stage and screen.

The new temples of the arts

There’s a cultural building expansion under way, with fresh galleries and facilities in which to experience modern visions of the world.

It’s ‘look at moi’ as local drama has a moment

Streaming television services are investing heavily in Australian stories, and audiences can’t get enough.

Curtain call: ‘How lucky are we?’

Australia’s musical theatre is booming and seeking to make up for time lost in the pandemic.

Key change as the show goes on, again

After a livelihood-destroying two-year hiatus, the live-music industry is joyfully finding its feet again, much to the delight of audiences.

Artist’s Vivid example of making a mark

The gods must be smiling on Sydney artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran, a Sri Lankan migrant whose riotously colourful sculptures have captured the public’s imagination.

Close-up: the system finds its stars

Who will be our next Cate Blanchett or Russell Crowe? There must be something in the water, as talented young Australians are taking over the stage and screen.

Arts & Culture list: our panel

We put together an expert panel of journalists to compile the inaugural list of 100 game changers in the arts. Learn more about the panel.

“I wasn’t what was expected,” he says. “I was always drawing, playing with the girls; I didn’t want to play cricket or with guns. I just liked different things and they didn’t have an avenue to understand what I was interested in.”

Despite his early aptitude for and interest in art, it wasn’t an area his parents were familiar with, even if they’d wanted to be. “At the time the galleries and museums in Sydney weren’t very welcoming spaces,” Nithiyendran says, noting that Australia was at its Pauline Hanson-induced xenophobic worst. “And it wasn’t like migrant families would encourage their children to pursue art. When they’ve just left their country and are struggling, as if they’d want them to make paintings for a living,” he adds with a laugh.

Nevertheless pursue art he did, studying painting and drawing at UNSW Art & Design, majoring in women’s and gender studies, before adding a Master of Fine Arts (with first class honours, no less). But it was a frustrating, unsatisfying experience.

Not only did Nithiyendran have little interest in the formalism and photorealism being taught, preferring an imaginative, expressionistic style, no matter how hard he looked he couldn’t see himself in anything he was learning. “We never looked at artists from other regions; it was always Europe or the US, never China or India or Africa,” he says. “I felt really frustrated as a young adult at university with not understanding how I could see myself fitting in the art world.”

So he invented his own niche. “This sounds really unromantic, [but because] I’ve always been really analytical I could look at the different parts of the industry and the different parts of my practice and see how I could make changes and find my own space.”

In 2013, the year he graduated, Nithiyendran held his first solo exhibition – a selection of ceramics at Sydney’s respected, artist-run Firstdraft gallery – and never looked back.

‘People often say to me ‘your work is so wild’, and there’s a sense people respond to it because they see something they want to have in themselves – they want to be more free or unrestrained or uninhibited’

In 2015, he won the prestigious Sidney Myer award for ceramics, and by 2016 he’d made it to Canberra with a solo exhibition, Mud Men, at the National Gallery of Australia. Another solo exhibition, In The Beginning, at Melbourne’s Ian Potter Museum of Art followed the same year and he was picked up by Sullivan+Strumpf not long after. A tax-free $160,000 Sidney Myer fellowship in 2019 gave him the financial and creative freedom so craved by artists to pursue his practice for the next two years.

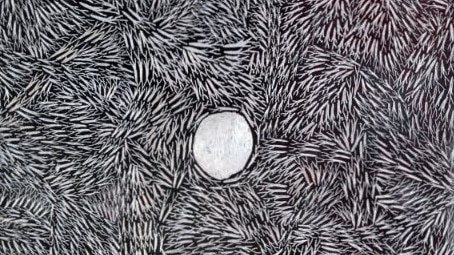

Nithiyendran’s works stem from an eclectic interest in a broad range of subjects, from his own Hindu and Christian heritage (he is an atheist), to politics relating to idolatry, pornography, fashion and art history. You’re never unsure whose work it is when presented with a Nithiyendran sculpture, with their bold, bright colours, tactile quality, and fun yet unsettling visages.

Interestingly, this crazy, expressionistic explosion of colour and form evolves through a methodical process requiring patience and precision. The artist’s formal training is evident in the fact that he begins each new piece by drawing or painting thoughts and concepts in a diary, mapping out his compositions. He works with sculptural clay, preparing the work, building up the general structure, adding details such as nose, eyes and mouth, then leaving it to dry for two and a half weeks. The sculptures are then baked in a kiln and glazed no less than four times apiece.

A detailed, large-scale, multi-dimensional installation such as the AGNSW’s Avatar Towers took six months to make, but Nithiyendran is quick to point out that it’s a team effort. “When you see exhibition imagery it’s just the artist standing there, but there are so many people working on it, and it’s not just the curator. What’s never visible is the infrastructure I have around me that helps make sure all the parts fit together. I had a team of 10 at the AGNSW; I have my assistant, Sullivan+Strumpf and Jhaveri Contemporary who make it happen.”

Today his works command between $4000 for a small sculpture and $17,000-$18,000 for a piece containing multiple parts. His work is held by institutions from the NGA to Bendigo Art Gallery, Artbank and the Powerhouse, in addition to a number of private collections. What is their appeal?

“People often say to me ‘your work is so wild’, and there’s a sense people respond to it because they see something they want to have in themselves – they want to be more free or unrestrained or uninhibited,” he says.

For Nithiyendran, it goes deeper than that. “The expressions are never simplistic and that’s how I like them to be; I always try to have that ambiguity. On the most basic level it’s a smile, but it could also be a menacing grin – it pushes at these strange, emotive spaces. I think that’s more reflective of the world and its complexity.”

He also has his detractors. “The most obvious criticism or comment is, ‘my child could have made that’, which is fine,” he says, chuckling.

“I don’t see that as a bad thing, I like to break down that hierarchy, that art is about training, this crafty skill. People should not like the work; expecting everyone to like it is unreasonable – there’s a spectrum of taste.”

What does hit hard is when the comments are fuelled by racism and discrimination. “One of the criticisms of the HOTA work on Instagram was, ‘It should have gone to an Australian artist’ – xenophobic, racialised comments. You’d be shocked by how often discriminatory comments have racialised undertones. That’s just part of the package of being in this space, but that’s one of the hard bits.”

What makes it all worthwhile, and what matters most to Nithiyendran, is the visibility he’s providing to a younger generation of migrant kids who might now follow their artistic dreams, confident someone has paved the way before them.

“In the Sri Lankan or Tamil community, people see me as a leader,” he says.

“There’s a perception I’ve created a space for people to see themselves in, really mainstream institutions [where] I’ve brought in works that are Asian and south-Asian, so they’re more regionally relevant to where we are geographically. I think that visibility helps a lot of people. As a young adult I would love to have seen that as I was learning about art. Every now and then I get a message on Instagram [from an emerging artist] saying how amazing it was to see someone of their ethnicity being represented in positive ways, because migrants are often referenced through a lens of crime.”

Although we’re sitting down in his studio relaxing over a soothing cup of freshly brewed mint tea, it is clear Nithiyendran is a man in demand. His phone pings continually, and we are surrounded by a seemingly ever-expanding tribe of guardian figures, gargoyles and beasties in various stages of completion. The artist is working around the clock to finish his large-scale sculptural commission for Vivid Sydney. Titled Earth Deities (part of the Dark Mofo series), the 7m tall, multi-limbed sculpture has four faces and 98 lighting channels and will, in the words of its creator, “be absolutely wild”.

The installation will sit harbourside on the grassy reserve with the Sydney Opera House to its right and the Harbour Bridge above. “That site is so monumental so we wanted something that felt monumental but handmade … bold enough so as not to be dwarfed by the iconography that surrounded it,” he says. He is particularly excited by this work, noting it’s the first time he’s presented something of this scale outdoors in Sydney. “It sounds parochial but it always feels special to show something like this in your hometown.”

There’s more to come. Sullivan+Strumpf is holding an online exhibition of 15 new works this month and next; in July, Nithiyendran’s 400-page monograph will be published by Thames and Hudson in Australia, the UK and the US; his work will feature as part of Sydney Contemporary art fair in September, and his beloved Avatar Towers is being rejigged on bright pink scaffolding as part of the AGNSW’s Sydney Modern grand opening in December. “I’ll have my dance card pretty full,” he says, laughing.

Now that his drawings and artworks are in galleries and collections all over the globe, are his parents more comfortable with this mysterious world their son inhabits and works in for a living? “I think my parents struggled to understand what I was doing until it became visible in places that were intelligible to them, once the media started coming in and it wasn’t an art journal. Taking them to the NGA for my exhibition in 2016 was a pivotal moment,” he says.

“They also see I have a comfortable lifestyle,” he adds with a chuckle: I’m not struggling financially, and I have nice furniture. But at the same time, I am here six days a week, by myself, getting filthy. Not that that’s a complaint.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout