The rainmakers see more ways to source funds

Arts philanthropy has embraced the digital age, with the constraints of the pandemic spawning new schemes to buttress the cultural bottom line.

Every time you wave a debit card at the supermarket checkout, or hit the purchase button online when buying concert tickets, a payments system shaves off a percentage as commission for its service. These micro payments have become a fact of shopping in the digital era, and the electronic platforms that collect them make up a global, trillion-dollar industry.

Three friends – Marc Goldenfein, Lara Thoms and Alistair Webster – noticed all that loose change being dropped into the pockets of multinational corporations and started to think about how they could divert some of it towards the arts.

Thus was ArtsPay born: an electronic payments business linked to a philanthropic foundation. The idea is that 50 per cent of ArtsPay’s commercial profits will be handed to the ArtsPay Foundation, which in turn will make grants to artists and small to medium arts companies. While the details are still being worked out, Webster says the Melbourne-based foundation will be up and running later this year, and eventually could distribute up to $10m a year.

“With ArtsPay, every time anyone uses a credit or a debit card at an ArtsPay business, they are helping to support the arts – it becomes an ongoing stream of revenue,” he says. “Whenever you buy a coffee, whenever you buy a book, or a ticket to a gig, you can help support the arts.”

Fintech meets philanthropy has a nice ring to it, and ArtsPay is just one of several new ventures that are using digital technology to fulfil a non-profit cultural mission. The Australian Digital Concert Hall was co-founded by Chris Howlett and Adele Schonhardt during the first months of the pandemic in 2020 to connect audiences and musicians online. It has distributed ticket revenue to musicians to the tune of $1.7m. Another new venture is Light ADL, a social enterprise in Adelaide that combines a working restaurant and a hi-tech LED installation that is available to artists as a kind of digital canvas.

Jack Heath, chief executive of Philanthropy Australia, sees a growing connection between philanthropic endeavour, technology and cultural outcomes. A younger cohort of philanthropists is closely tied to technology as both a source of wealth and as a channel for social good.

“Where there is scope for significant increases [in philanthropy] it is with younger people who are using more of the new forms of media, and where their philanthropic dollar might go,” he says. “They might not be going so much into the traditional areas, but things around virtual reality and those new territories. That’s where I think we will see increasing interest from young philanthropists.”

Philanthropy, of course, is still done the old-fashioned way, where donors may give millions of dollars to support the acquisition of a painting, a new ballet or opera production, or to help build a brand new museum.

A sensational new benchmark in philanthropic giving was reached in April when trucking magnate Lindsay Fox and his wife Paula gave $100m towards the building of NGV Contemporary, the contemporary art wing of the National Gallery of Victoria that is due to open in 2028. It is the largest cash gift ever to an Australian arts institution – exceeding even the legendary Felton Bequest that has given the NGV so many valuable artworks.

As observers have pointed out, what makes the Foxs’ gift so extraordinary is that it has been made during their lifetime, not as a legacy or bequest. The donation puts NGV Contemporary firmly on track to reach a fundraising target of $200m, following an earlier donation of $20m from the Ian Potter Foundation.

See The List: 100 Arts & Culture stars

A characteristic of NGV Contemporary and other major capital works – such as the Powerhouse Parramatta and Sydney Modern – is that they are public-private partnerships, built from a combination of government grants and private philanthropy. Often, they are legacy projects for major donors, involving gifts in the tens of millions. The cornerstone donation for Sydney Modern was $20m, later raised to $24m, from reclusive Sydney couple Susan and Isaac Wakil. Their support was pivotal to the NSW government making its budget commitment of $244m. The Art Gallery of NSW has raised $109m for Sydney Modern, due to open later this year. Another major gift is property developer Lang Walker’s $20m to support a learning academy at the Parramatta Powerhouse.

There’s an element of “show me the money” in these public-private partnerships. Mark Quigley, an adviser on capital campaigns through his company Social Venture Consultants, says there’s an expectation that both governments and major donors will contribute to major cultural infrastructure.

“You need the government investment if you are going to your philanthropists and asking them to contribute,” he says. “If you look at some of the capital works projects that have gone on, and the cornerstone investment by government, both at a federal and state level across the country, there is a lot to be excited about if you are in the arts sector.”

Donors support things other than new buildings. The Australian Ballet recently launched a campaign for a new production of Swan Lake next year, to be directed by David Hallberg. At least $2m had already been secured before the campaign went public, with donations from Lachlan and Sarah Murdoch, through their personal foundation, and from the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation, named for the Adelaide ballet-loving couple.

John Kaldor is famous for his philanthropic ventures in contemporary art, especially for the five decades of Kaldor Public Art Projects, and the 2008 gift of his $35m art collection to the Art Gallery of NSW.

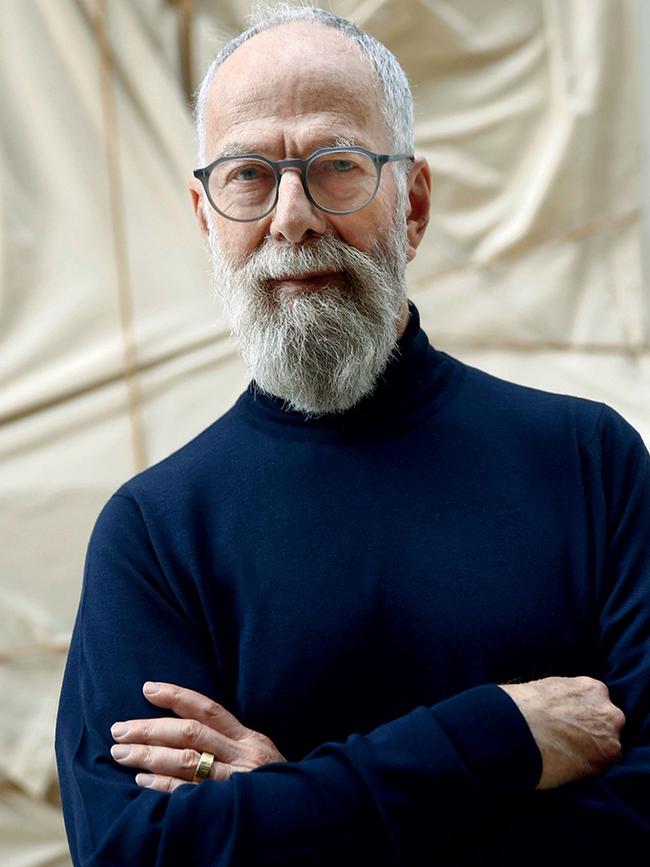

Another project that has relied on private-sector contributions is the UK/Australia Season, a cultural exchange program between the two nations. It will support the British season of S. Shakthidharan’s play Counting and Cracking and concerts by the Australian World Orchestra at the Edinburgh International Festival, as well as tours by other Australian groups. The largest single donor to the UK/AU Season is Lord Michael Glendonbrook, the British aviation millionaire and life peer who spends part of each year in Sydney.

“I have a real love for Australia,” says Glendonbrook, who gave $1m to the Season. “This is why we plunged in with the cultural exchange … I wouldn’t like to see the links between the two countries get separated. I think one should try and keep the links going, because there are so many people who come backwards and forwards all the time.”

The current value of philanthropic giving to the arts is difficult to calculate, partly because sector-wide studies are infrequent, and because the impact of the pandemic and natural disasters on private giving has not been fully factored in. Creative Partnerships Australia, the federal government body charged with building private-sector support for the arts, reports that cash donations and sponsorships increased to $378m in the 18-month period to June 2020, a 7.7 per cent rise on 2018. But overall support for the arts declined by 11 per cent once non-cash contributions, such as volunteer hours, bequests and sponsorships in kind, were included. The survey period only captured the first few months of the pandemic.

There’s an element of ‘show me the money’ in public-private partnerships, an expectation that both governments and major donors will contribute to major cultural infrastructure

Another study of philanthropy across different not-for-profit sectors is bleak. Total donations fell sharply in the first year of the pandemic to December 2020, reversing the gains of the previous five years, according to the JBWere NAB Charitable Giving Index. The culture and recreation sector, including the arts, had the steepest fall of all, as the value of total donations plummeted 60 per cent.

One picture that emerges is a gap between levels of giving to the arts, and between the kinds of organisations that are able to attract substantial donations. Evidently, there is capacity among the richest Australians to give generously. Even through the pandemic, investment classes such as shares and property performed well. The JBWere report notes that philanthropy at the top end by ultra-high-net-worth individuals has remained strong, even while overall giving has declined.

Major donations such as the Foxs’ $100m are extraordinary in every sense: they are transformative for the organisations they benefit, and they capture the headlines, but they can tend to skew the overall picture. What appears to be happening in philanthropy is strong support at the uppermost level but a decline in mid-range giving.

“When we are looking at general trends in philanthropy in Australia, the mums and dads, there is less giving happening there,” says Philanthropy Australia’s Jack Heath. “But where we are seeing more giving is at the high end. It’s individuals of significant wealth who are really sustaining things at the moment.”

Similarly, there’s a gap between different kinds of arts organisations. Capital campaigns for new museums, and fundraising by major performing arts companies to support a new opera or ballet production, tend to attract the philanthropic dollars. Such campaigns have dedicated professional fundraisers, and can often lean on the networks of their high-profile boards. Smaller companies lack those resources and pulling-power. And while major companies are grateful when ticketholders donate the value of their tickets – rather than claim a refund when Covid has caused performances to be cancelled – smaller companies may not be able to count on that support.

The arts sector, as a whole, also has to compete with other not-for-profit sectors. Natural disasters have taken a huge toll on the nation in recent years, and Australians have responded where there’s been need. The pandemic, too, has exposed gaps in the safety net for the most vulnerable Australians. Quigley expects the post-Covid recovery in philanthropic giving will likely follow a K-curve: some sectors will track gains, others will decline.

“Some organisations and sectors of the not-for-profit community, including the arts, will go up, and some will go down,” he says. “That was a fact of life pre-Covid, but Covid has highlighted the need for even more giving by high-net-worth individuals and ultra-high-net-worth individuals. They are going to have to be, to some degree, selective about who they give their philanthropic funding to.”

What is the future for philanthropic giving in Australia, and how will the arts benefit? Some Australians have become very wealthy. Homegrown technology companies such as Atlassian, Afterpay and Canva have made billionaires of their founders. Melanie Perkins, one of the founders of Canva, the online graphic design platform, has said she plans to give her $16.5bn fortune away.

There is also the massive store of private wealth that will be inherited by younger generations in coming years. An estimated $2.6 trillion is expected to change hands between now and 2040, and $1.1 trillion across the next decade. Philanthropy Australia sees the intergenerational wealth transfer as an opportunity to substantially boost support for charitable and not-for-profit causes. It proposes tax reforms and other initiatives to help double private giving from about $2.4bn in 2021 to $5bn by 2030.

It could produce a windfall for the not-for-profit sector, including for the arts, although David Gonski is careful not to get carried away. The philanthropy guru who led the campaign for Sydney Modern says that it can’t be assumed that billions of dollars will magically be transformed into donations. The generation inheriting the wealth may not be inclined to disperse it, unless there is a family precedent or a strong drive to contribute philanthropically.

There’s also the question of priorities. Can the arts be assured of ongoing philanthropic giving when there are so many other important causes, from social welfare to medical research and the environment?

Gonski says the arts is fundamental to a healthy, functioning society – but arts leaders will have to continue to make the case for support.

“Some people think that some parts of the arts are for very wealthy people – that’s just not correct,” he says. “In my opinion, the arts are a very important part of one’s whole community … it’s not just a pursuit for the wealthy, the black-tie dinners or whatever. I feel very strongly that the arts are for everybody, and that everybody does participate in the arts.”

There are complications as well as many opportunities for those who want to see stronger support for the arts from the philanthropic community. But it may come down to a simple proposition: that people give money to the things they care about, and where they can make exciting things happen.