Stimulation of the Australian economy could backfire in 2022

When this decision was made, Australia was on the brink of disaster – but 18 months on, it could be the thing that sends our economy spiralling.

In life there are few things more inconvenient to deal with than a car with a broken fuel gauge. Despite methods to estimate how much fuel you have left, more often than not you’re left guessing until it finally conks out on the side of the road.

With this, the current Australian economy shares quite a lot in common.

We know the government put a whole heap of fuel in when it committed to $507 billion in stimulus measures when the pandemic began, but as for how much actually is left in the tank now, we can only make educated guesses.

In the more than 18 months since the pandemic began, educated guesses have been pretty much all economists and analysts could do a large proportion of the time.

At first, the consensus was that Australia would experience a near ‘Great Depression’ level hit to the economy and face a long road to recovery.

Then as the economy reopened and it became clear that Australia was coping with the virus far better than pretty much anyone had anticipated, forecasts were cautiously revised upwards.

Yet despite these upward revisions, the Aussie economy once again surprised pretty much everyone with its resilience and the swiftness of its recovery.

While there are a number of different reasons for this, arguably the most important, was the size of the Morrison government’s stimulus programs.

A big spending government

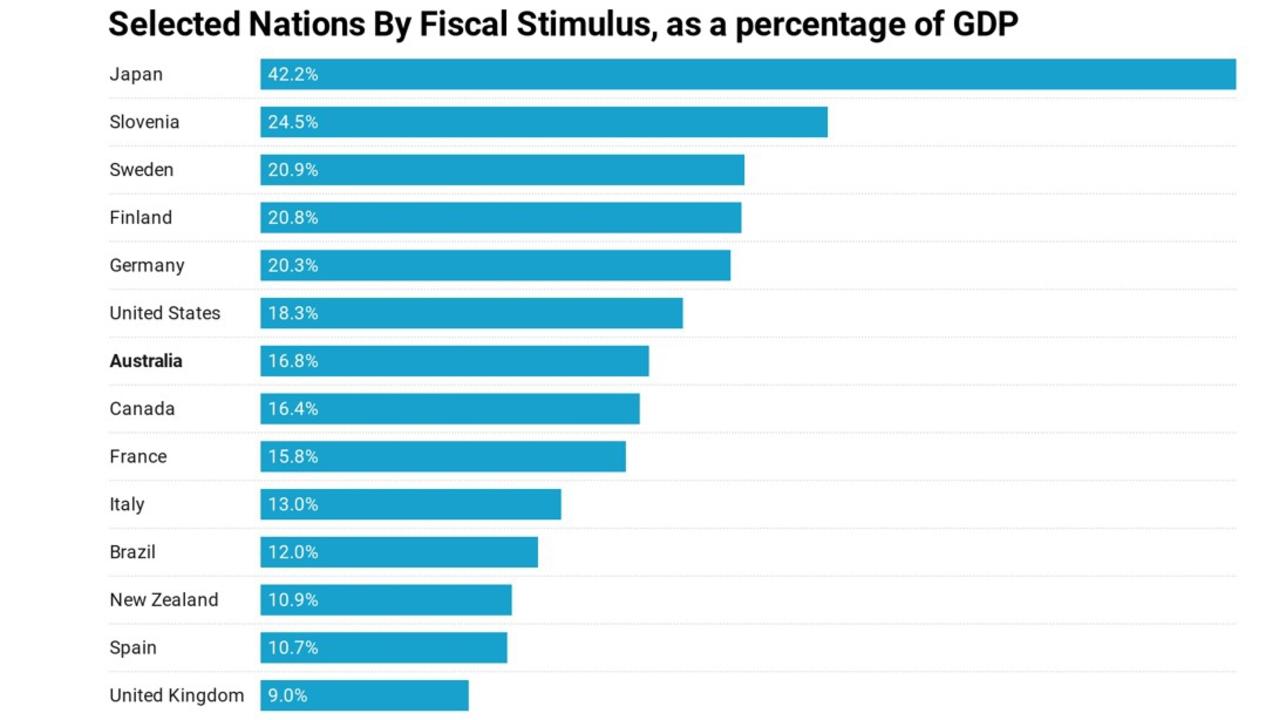

At more than half a trillion dollars, the Morrison government’s stimulus commitment was the largest non-wartime expenditure commitment in Australian history.

In fact, when contrasted with other nations for the majority of the 2020 calendar year, Australia spent almost twice much as Britain index to GDP and was only slightly behind the United States.

Both nations were extremely hard hit by the pandemic, yet despite Australia’s world-beating management of the virus at the time, the enormous stimulus continued.

To put the level of stimulus in perspective, it’s roughly in the same ballpark as the budget deficit for the final year of World War II, from which Australia emerged with one of the most powerful armed forces in the world.

Yet despite the strength of the economic recovery from the pandemic, in terms of boosts to business productivity or new infrastructure, Australia doesn’t have a great deal of long term benefit to show for the hundreds of billions of dollars in new debt.

Inflation and interest rates

Earlier this week, Prime Minister Scott Morrison was well and truly in campaign mode, claiming that under Labor, petrol and electricity prices would go up and that interest rates would “go up, more than they need to”.

In this single sentence Mr Morrison hit on two key pain points for Aussie household budgets, the rising cost of living and the potential for interest rates to rise.

In the coming months these two issues are likely to be hotly contested in the halls of parliament, as Australia gets ready to go to the polls for the next federal election next year.

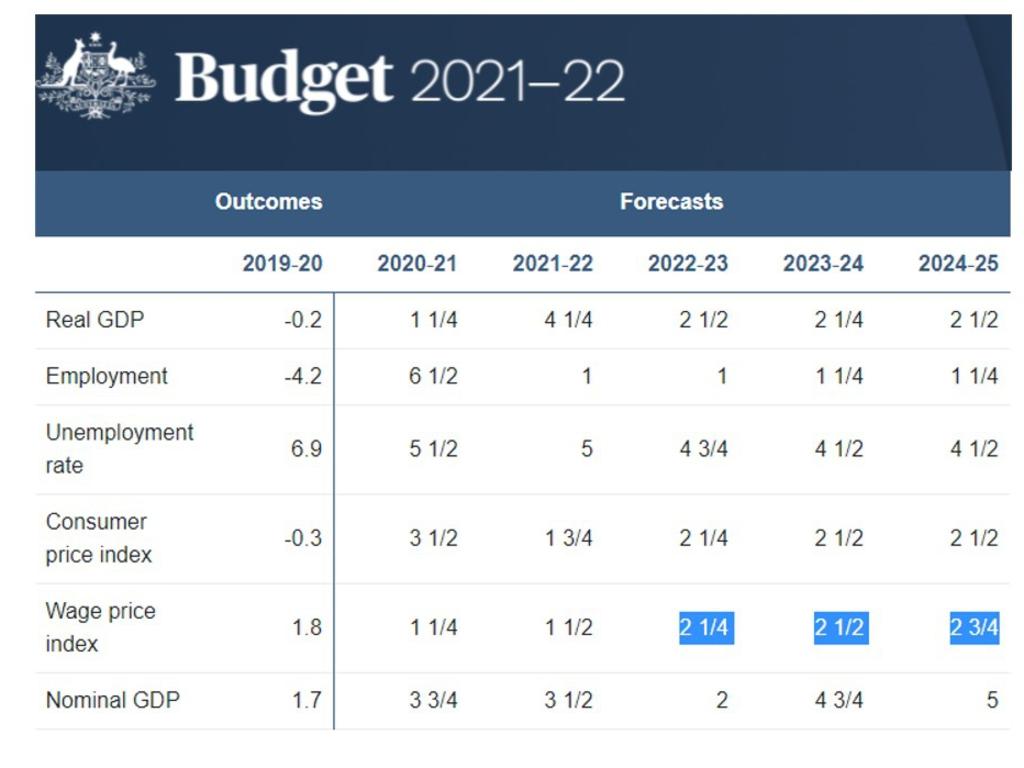

With the budget expecting zero wage growth after accounting for inflation until the 2024-2025 financial year, where it is expected to eke out just a 0.25 per cent gain, consumer prices are rising faster than Treasury’s forecasts and interest rate rises could present a significant challenge to the economy.

A King’s ransom in savings, but will they be spent?

By the end of the year, it is estimated that Aussie households would have saved roughly $200 billion since the pandemic began.

While this is an enormous sum of money, it is only a fraction of the more than $1.2 trillion of bank deposits held by households.

There is a popular narrative that a large proportion of these savings will be spent in a huge blow off in consumer spending, as the economy finally reopens to what is hoped is a post-pandemic Australia.

But whether or not that will actually happen or not is another thing entirely.

In the United States, the level of household savings since the pandemic began is more than $2 trillion, yet despite holding an unprecedentedly large amount of cash, the attitude of American’s towards major purchases has collapsed to its lowest level in almost 40 years.

This is arguably due to the impact of rising inflation, with rising fuel, housing and food prices hitting American households particularly hard.

As a result US consumer confidence is now by some measures worse than during the dark days of the initial lockdowns early last year.

Whether the American experience of high inflation is a preview of what Australia will face remains unclear, but it is already raising eyebrows in parliament and in board rooms across the country.

A foggy crystal ball

To what degree inflation and interest rates will drag on the economy in 2022 and beyond is unknown, as experts and central bankers alike continue to debate on what path inflation will end up taking.

The truth is Australia and the world are in uncharted economic waters, never before has so much money been thrown at the global economy with so little regard for value for money or the potential long term consequences.

In late 2020 and in 2021, the Aussie economy surprised pretty much everyone with its resilience, leaving many analysts now quite optimistic about its future prospects.

Ultimately, the nation’s economic fuel gauge remains broken and how many kilometres we have left in the tank remains a mystery, we could have more than enough left to see us through 2022 or the economy could splutter to a crawl far sooner than many of us expect.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator