How iron ore commodity crashes will result in low Aussie inflation

Rising interest rates, commodity crashes and fear of inflation could spell a disaster for the Aussie economy but everything might not be quite as it seems.

ANALYSIS

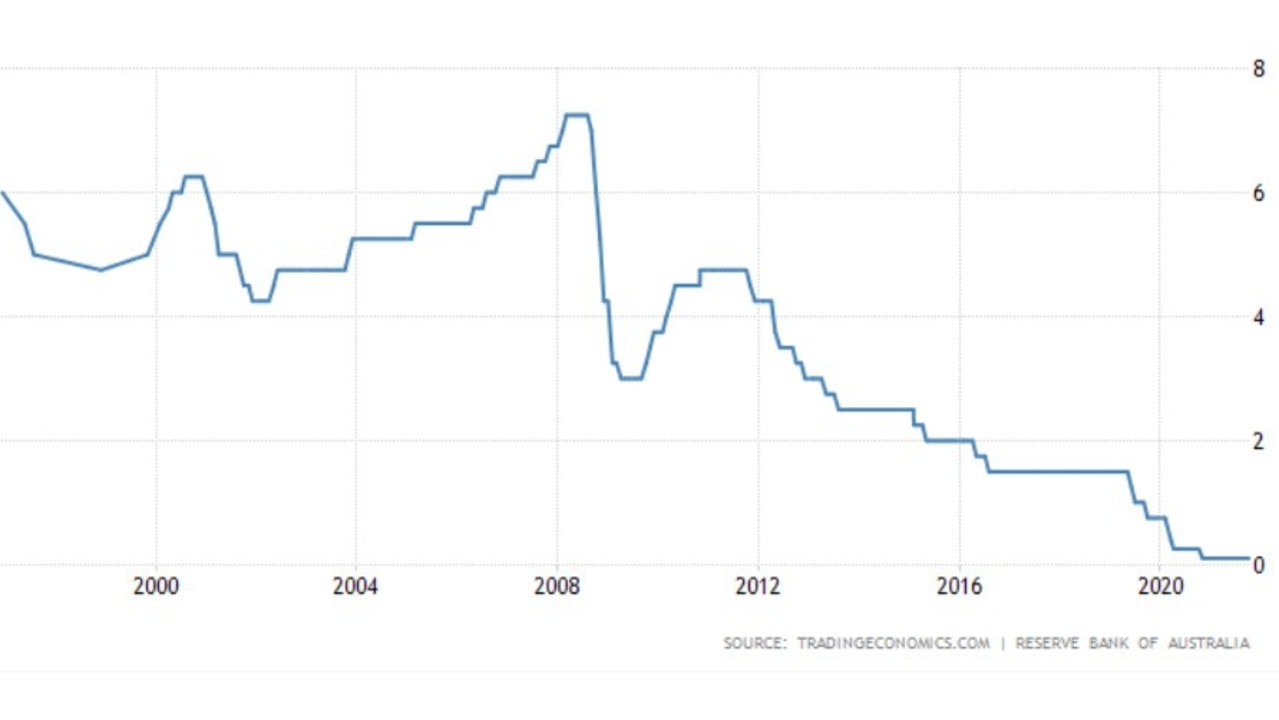

Last week Australia witnessed a historic breaking of the Reserve Bank of Australia by markets. At the start of the week, the RBA was insisting that it would not lift interest rates before 2024. By Friday, it had capitulated to bond market pricing that it would hike rates five times in the next year.

This staggering humiliation of the RBA was driven by two main factors.

The first was building global inflation panic around supply-side constraints in the global economy arising from Covid distortions.

The second was a firm local inflation print that pushed the core consumer price index (CPI) within the RBA’s 2 to 3 per cent band for the first time in six years.

This was enough for the traditionally labelled “bond vigilantes” to storm markets and force a bowel-shaking repricing of Australian interest rates.

Yet, when we peer under the bonnet of these factors, they are not very convincing.

Global inflation is being driven by a range of unsustainable factors more related to economic reopening than by sustained economic expansion.

Supply-side inflation emanating from pumped-up American goods consumption will ease over the next year as services spending rebounds with an easing pandemic. Chinese export capacity constraints will likely collapse as American goods demand eases.

China’s crazy energy shortage is already over and power raw materials like coal are crashing.

Semiconductor shortages that are holding back car production around the world are easing as we speak.

Next up, congested logistics like ports, shipping, containers and other transport are all going to unclog after the Christmas rush subsides.

All of these supply-side inflation pulses are temporary and should revert to pre-Covid prices the moment that bottlenecks clear. Which appear to converge around the new year.

The second factor driving global inflation is that markets fearing inflation have bid up commodity prices as a hedge.

This has, in turn, created more inflation as input prices rocket higher. But as the supply-side prices collapse that rationale will also fall away and those hoarding raw materials against a more expensive rainy day will panic sell.

This will be made much worse by the Chinese construction market collapse which is worsening by the day and sucks in roughly 40 per cent of global metals.

In short, probably through the first half of 2022, a convergence of severe price falls is likely in the global economy. These price falls should be permanent as the crazed post-Covid reopening cycle reverts to a normal economy and Chinese construction is structurally curtailed.

This should aid in suppressing Australian inflation. In particular, the commodity price falls will deliver an enormous income shock vis crashing terms-of-trade. Iron ore, the two coals, LNG and many metals will at least halve in price over 2022.

That will hit Australian nominal growth hard, sit very heavily on wages and trigger a dramatic reversal in the fiscal support currently underway throughout the economy as budget deficits soar.

We will also see a return of Australia’s controversial mass immigration policy which has little public support but is loved by all parliaments and business rent-seekers, largely because it heavily suppresses wages growth.

As the Australian economy reverts to pre-pandemic trends, our own burst of inflation should subside. Although it may be marginally stronger than before Covid thanks to tighter labour markets, it won’t be enough to matter much to interest rates.

This is why the RBA should never have allowed itself to be bullied by hysterical bond markets which last week priced an interest rate shock right at the precipice of a great and global inflation bust.

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and MB Super. David is the founding publisher and editor of MacroBusiness and was the founding publisher and global economy editor of The Diplomat, the Asia Pacific’s leading geopolitics and economics portal. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review. MB Fund is underweight Australian iron ore miners.