Hyperinflation: What is it and are the current warnings valid?

After almost two years of economic instability and a pandemic, the next fear is that hyperinflation could be coming for us.

Former US President Ronald Reagan once said, “Inflation is as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man.”

After a challenging period of high inflation throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Reagan’s words cut deep for a generation that had seen skyrocketing petrol prices and the cost of living rising by over 13 per cent in the year he came to office.

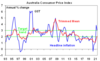

For well over a decade the issue of inflation has generally slumbered throughout much of the Western world, as consumer prices indexes generally trended down and interest rates continued to be cut.

In April 2019, the magazine Bloomberg Businessweek went as far as asking “Is Inflation Dead?” and speculated on some of the potential downsides.

On today of all day's I thought I would wheel out this hot take from 2019... pic.twitter.com/sGJ5brDbpW

— Avid Commentator 🇦🇺 (@AvidCommentator) October 28, 2021

Yet two and a half years and a pandemic later, the question is no longer – is inflation dead? Instead, it’s – could we see hyperinflation?

What is Hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is a rapid and excessive increase in consumer prices, technically defined as prices rising by more than 50 per cent a month or 1000 per cent in a year.

It is a term that evokes a certain image in the public’s collective consciousness, of grocery bills in early 1920s Germany being paid with wheelbarrows full of near worthless money and children playing with piles of cash that were worth less than the paper they were printed on.

Historically hyperinflation has been triggered by a number of different reasons, such as wars, acute shortages of goods and excessive money printing.

While hyperinflation is generally a product of the modern era, according to a study conducted by Johns Hopkins University, there have been 57 cases of hyperinflation since 1795 – with all but two occurring within the past century.

The worst hyperinflationary event in history occurred in Hungary shortly after World War II, where monthly inflation peaked at 41.9 quadrillion per cent (41,900,000,000,000,000 per cent). Believe it or not that is correct number of zeros, prices were rising so rapidly that they doubled roughly every 15 hours.

Hyperinflation Warnings

Last week, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey made headlines around the world by stating on Twitter that, “Hyperinflation is going to change everything. It’s happening.”

As an incredibly well connected tech mogul with a net worth of more than $US14 billion ($A18.5 billion), Dorsey’s warnings prompted a great deal of concern from some quarters, that the Twitter CEO’s prediction could be right.

Dorsey isn’t the first high profile individual to raise the alarm on hyperinflation potentially becoming a major issue.

In February, hedge fund manager Michael Burry compared the fiscal and economic situation in the United States with those of Weimar Germany in the early 1920s.

Burry became a household name in the world of finance in 2015, after the film The Big Short immortalised his role in predicting the American subprime mortgage crisis that would ultimately lead to the global financial crisis.

Through a long list of comparisons with early 1920s Germany, Burry shared multiple examples of how the United States was on a similar path of financial market and government spending excess.

From the participation of everyday people in pursuit of easy money in financial markets, to a government spending induced boom preventing business failures, Burry shared example after example of the similarities.

Burry pointed out that the current high valuations in global asset prices were very similar to those experienced in 1920s Germany before hyperinflation took hold.

The Consequences of Hyperinflation

Throughout history, high levels of inflation have been the catalyst for social instability and in some cases, the outright collapse of governments and empires.

In Germany, it contributed to the rise of the Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party and played a role in undermining faith in the existing elements of the political system.

In Venezuela, extremely high inflation and finally hyperinflation led to what can only be described as a collapse of the nation’s economy.

In 2012, Venezuelan GDP sat at an impressive $US352.2 billion ($A467.5 billion), as Caracas enjoyed the windfall of high oil prices and high levels of government spending.

By 2022, it is estimated the Venezuelan economy will have a GDP of just $US40.4 billion ($A53.6 billion), making it less than 12 per cent of the size it was a decade earlier.

To say that hyperinflation would be a disastrous outcome is an understatement.

Even historically high levels of inflation, where prices rise less in a year than they would in a hyperinflationary fortnight have been damaging to the social fabric in impacted nations.

But consumer prices don’t need to rise 50 per cent every month like in a hyperinflation scenario for inflation to begin to undermine governments and to create a volatile social environment.

The Likelihood of Hyperinflation

While the likes of Burry and Dorsey are raising the alarm about the prospect of hyperinflation, the likelihood of a textbook case actually happening is at most minimal.

The chances of your weekly grocery bill rising by 50 per cent in a single month are currently highly unlikely, at least in Australia.

But that doesn’t mean that high inflation, like the levels last seen in the 1970s and early 1980s are out of the question.

With the forces of deglobalisation and high energy prices to potentially contribute to the inflationary impulse for quite a while to come, a high inflation future is a scenario that cannot be ruled out.

Ultimately, the direction of inflation may be the defining economic and political question of this decade, potentially creating a butterfly effect of all sorts of consequences that we haven’t even begin to consider.