Mistake Albanese Government is making as we slide into recession

The glory years for Australia look set to be over as one “enemy” takes hold. And the Albanese Government might just be making it worse.

ANALYSIS

It used to be that Australians rarely experienced recessions. If we really squint our eyes and squeeze, we can even remember that two-decade golden age when everybody else had them but not us!

These days, recessions have become passé. In the past few years, we’ve had two officially and considerably more unofficially as Covid convulsions shook the economy.

But we should not become so complacent about the loss of income and wealth.

That is what the Albanese Government appears to be doing today.

Business cycles never die of old age

Unemployment is low and everything is good. That is when to expect a recession because that is also when inflation typically gets more heated and central banks tighten the screws on borrowers.

Australia is following this path. The Reserve Bank is being very aggressive about it. As the old saying goes: “Business cycles do not die of old age.”

All that we really need to ask at this point is: How bad will get? And what are the factors at play that will determine the depth of the downturn?

There are two types of recessions to consider. The first is that which is likely transpiring in places like the US where there are no big economic imbalances to adjust. These types of recessions are more like those that transpired in the 1970s with big equity bear (declining) markets, falling consumption and wild swings in inventory within business.

Believe it or not, this is the preferable type because it passes relatively quickly. The second version is worse – the balance sheet recession.

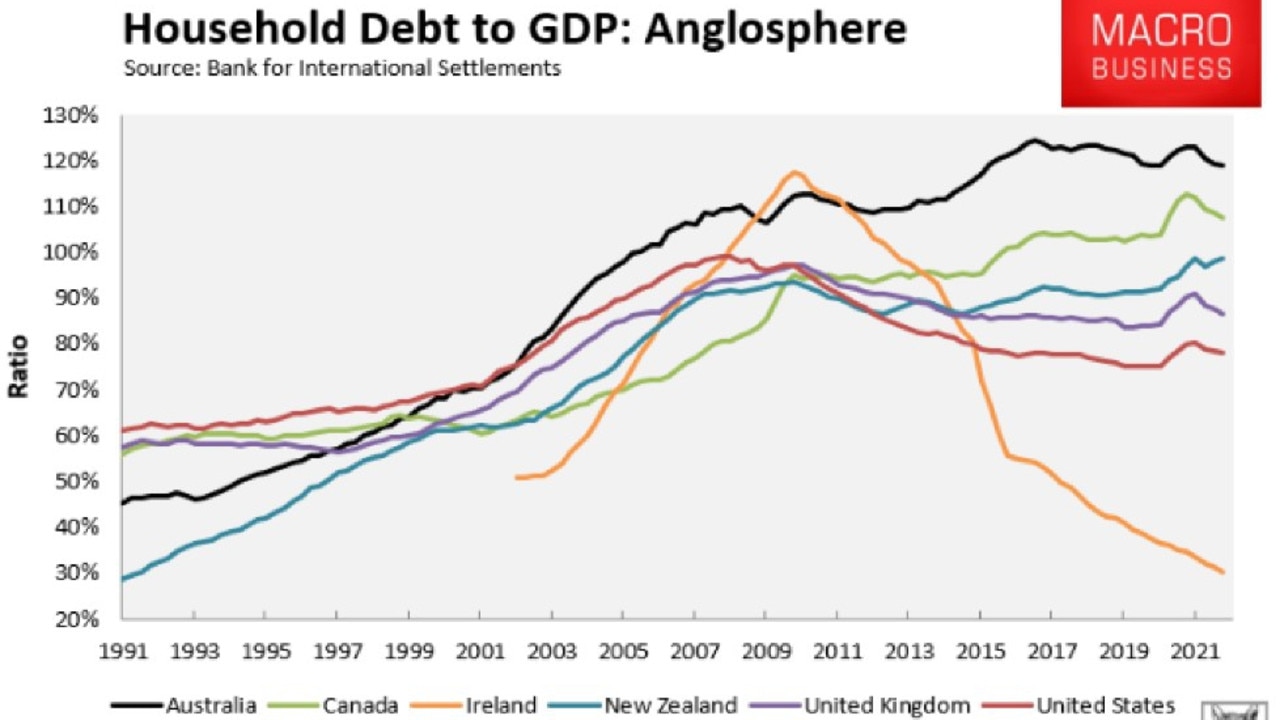

This is when macroeconomic (large scale such as interest rates and productivity) imbalances grow so large that they adjust dramatically under pressure from falling growth. A good example of this is the GFC recession in the US when household debt imploded along with property prices after a massive and unsustainable run-up in both.

In Australia, our last few recessions have been more the benign variety. We have never had a large enough shock to require our macroeconomic imbalances to adjust.

Albo making it worse

The major economic imbalance in Australia is household debt. The leverage build-up has taken 30 years and it is extreme.

This has been manageable through various global shocks because Australia always had the resources to bail it out when needed. This has come at the cost of enormous intergenerational inequity and the collapse of market integrity in banking and property sectors but we did it anyway.

The problem now is Australia faces the one enemy that wipes out those bailout resources – inflation. Last week, the RBA warned that it sees a range of inflation measures getting out of control over the second half of this year:

Ahead of the release of the June quarter Consumer Price Index (CPI) at the end of July, members noted that domestic inflationary pressures, including those outside of the labour market, continued to build.

Non-labour input cost pressures were evident across a range of industries. Adverse weather conditions had affected the prices of some fresh produce. Rents were expected to pick up in response to tightening rental market conditions across most of the country. Wholesale electricity and gas prices had also increased sharply in recent months, reflecting domestic supply disruptions during a period of increased demand.

The effect of these increases on electricity and gas prices was expected to be evident later in the year, since state subsidies and hedging arrangements had limited the near-term pass-through.

More generally, firms in the Bank’s liaison program had indicated a greater propensity to pass through cost increases to consumer prices. As a result of these price pressures, inflation was expected to increase in year-ended terms through the remainder of 2022.

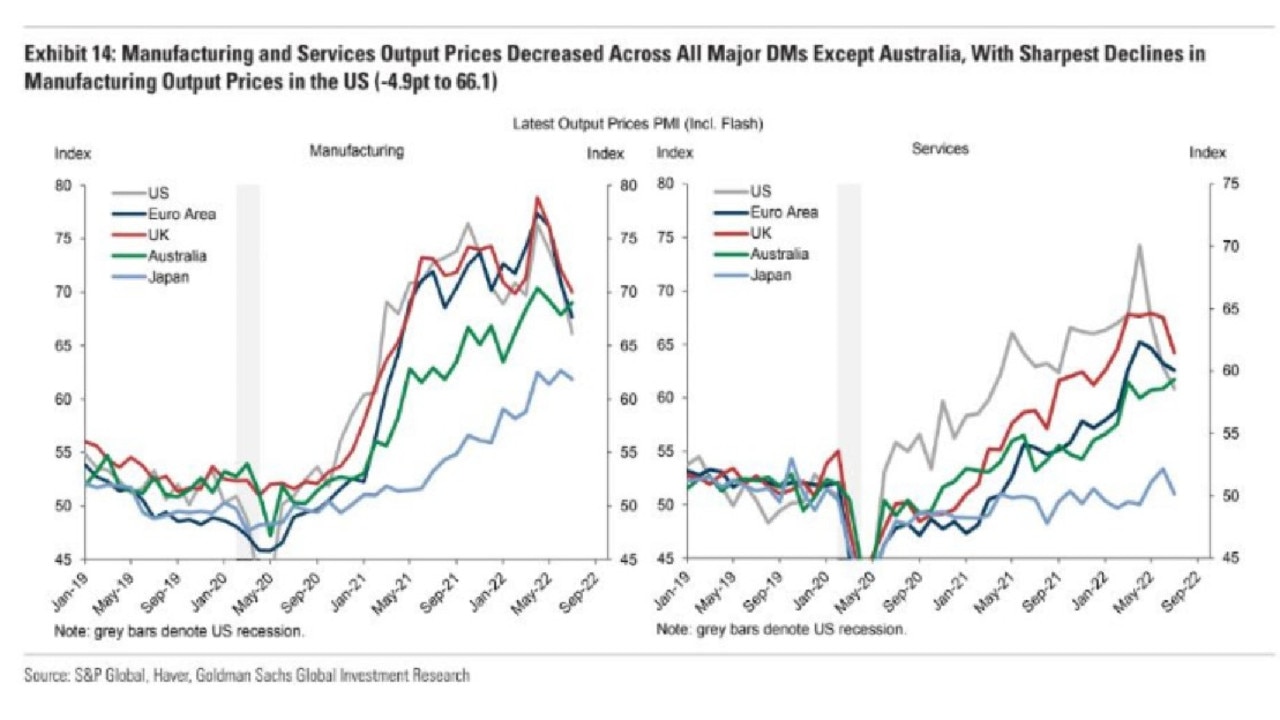

This inflationary outbreak mostly came from offshore and is already passing. However, the Albanese Government is responding to the RBA’s concern about rent, energy, food and profits inflation by committing two policy errors that mean locally bred inflation will now take off instead of foreign inflation wane.

First, it is opening the immigration floodgates. Normally, higher immigration might help lower inflation by crushing wages. But, contrary to popular belief, Australia does not have a wages breakout so any resumption of immigration will only ensure that wage income remains weak while a rents breakout is made considerably worse.

Albo’s second policy error is worse. It has been to protect the war profiteering of Australia’s gas and coal export cartels after the commencement of the Ukraine war. Gas and electricity are both up 600 per cent at the wholesale level. Between them, and by themselves, they will add 3.5 per cent to the CPI over the next year.

Worse, energy and food are bound together because gas and electricity are large cost inputs into food production. Energy will also inflate building costs via locally produced materials like bricks, gyprock, paint, metals. You name it.

Food and housing costs are 40 per cent of the CPI and Albanese Government policies are going to dramatically inflate all of it. This, before we even get to energy impacts on the other 60 per cent of services.

In total, Albo’s policies will likely add 5-6 per cent to the CPI over the next year as the RBA tries to reduce inflation. Within a few months, this could push Australian inflation to the highest in the developed world as everybody else deflates.

Albo’s catastrophic recession

Economists like to talk about the neutral interest rate. It is the rate at which growth can continue but inflation remains quiescent. Pre-Covid, this rate was somewhere under 1 per cent. Since then, Australian households and governments have added a lot more debt so it is even lower today under normal circumstances.

Mr Albanese’s errors are instead forcing the RBA to set the cash rate based upon a neutral interest rate artificially inflated by badly timed mass immigration and energy war profiteering. The result of this is predictable.

All recent and semi-recent borrowing that has transpired on the assumption of a sub-1 per cent cash rate is going to be distressed and shaken out. Most especially in households.

Those that took out mortgages on the RBA’s ill-fated 2 per cent fixed rates are looking set to roll off onto variable rates as much as triple the price, beginning now and for the next three years.

House prices are already crashing as this begins and, as the RBA chases Albo’s 6 per cent additional inflation shocker, Australians’ largest asset is going to sink more than we have seen in a century.

If the Albanese Government does not change course urgently, especially on energy policy, this risks becoming an unstoppable balance sheet reckoning for Australian households. A grinding and dreadful affair of wealth destruction that crushes profits, threatens banks, wrings out living standards and damages household psychology for a generation.

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and MB Super. David is the founding publisher and editor of MacroBusiness and was the founding publisher and global economy editor of The Diplomat, the Asia Pacific’s leading geopolitics and economics portal. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review. MB Fund is underweight Australian iron ore miners.