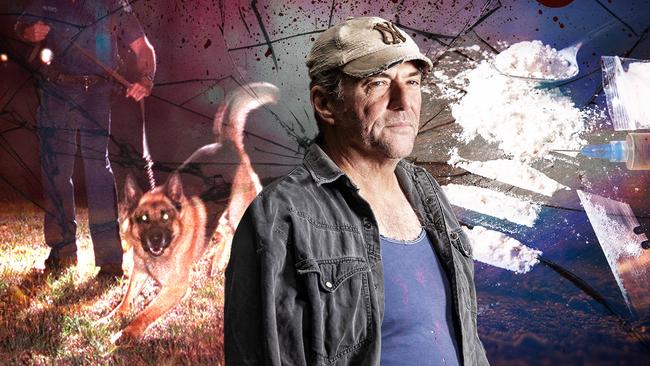

Undercover Cop podcast: How treachery of rat cops almost broke Lachlan McCulloch

Lachlan McCulloch arrived at his office in police headquarters to find his door kicked in, his filing cabinet forced open and a fresh dog dropping — a sign he was now condemned as a “dog”.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

This is part five in the Undercover Cop series. Catch up on the series and listen to the podcast here.

It took eight years to put a bent cop in jail with his co-conspirators, an ordeal that almost destroyed an honest cop.

Half a lifetime later, it still affects Lachlan McCulloch to talk about it. About how, night after night, he’d wake up on the couch in the small hours, his shirt wet with the last glass of wine he’d poured before midnight.

He drank to blot out the pain of being one out against the Brotherhood.

True, McCulloch had been legitimately scared for his life before, gaming killers like “Stacker” McKinnon and Trevor Pettingill and Trevor’s frightening mother, Kath.

He describes the evil grandmother as “a joking person you’d have a beer with in the outside world — but in her world, she’s scary.”

Although his police handlers had sometimes carelessly let him down during the Pettingill operation, at least they’d been on his side.

But the Pilarinos police corruption was something else.

The treachery of fellow cops would make McCulloch a pariah in the drug squad, threatening his life, his happiness and once brilliant career.

It all started with a tip-off in 1992.

The tip was that a suspiciously rich nightclub owner, Peter Pilarinos, was paying for drug-making equipment to equip a known “speed cook,” James Sweetin.

People running nightclubs were often top of the drug distribution chain, selling to a captive market for cash. Pilarinos was a gangster-businessman who cultivated tame police.

Crooks wanting to make amphetamines need both raw precursor chemicals and “glass”, specialist beakers and condensing equipment. Their “cooks” have to be scientifically smart enough to process volatile chemicals without blowing themselves up.

The tip-off about precursors wasn’t enough for McCulloch to get warrants to install listening devices in Pilarinos’s huge house in Doncaster East. But it prompted him to go there one night to get the garbage.

When McCulloch and his offsider went through Pilarinos’s trash, they found dog food cans. One can was folded up and tightly crushed. Inside it was a piece of paper torn into tiny pieces.

When they fitted the pieces together McCulloch saw it was a “shopping list” of bulk precursor drugs for amphetamines. Evidence that Pilarinos was handling “gear”.

The list also had other clues. Beside each material Pilarinos had written a volume and a cost.

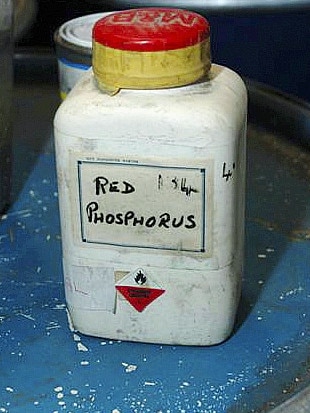

Some materials were controlled substances, hard to get and consequently expensive. Yet beside one of the most expensive ingredients, red phosphorus, Pilarinos had noted “$0”.

Why had the nightclub king paid for some chemicals but not others?

McCulloch wasn’t sure. Regardless, the list was strong evidence of intended amphetamines production, enough to get a warrant for listening devices.

The phone taps confirmed that the Pilarinos crew was preparing to cook amphetamines. And there was something else in the taped conversations: hints that police information was leaking.

In the clumsily “coded” exchanges, Pilarinos referred to “the fat boy from up north.”

As McCulloch knew, Pilarinos ran the Palace nightclub in St Kilda, where a lot of police drank — mostly without paying.

The cosy relationship with cops ran deep. The armed robbery squad’s huge annual “bash” was routinely held at the Palace.

But it wasn’t until there was a “wake” in 1993 for the old Police Club behind the Russell St building that McCulloch realised how sinister the Palace connection was.

The Police Club was moving and the farewell party was huge. A temporary stage was set up and strippers were hired as entertainment for a marathon drinking session.

For drunken cops, the night’s “highlight” was an explicit strip act featuring lolly snakes.

Next day, McCulloch was listening to taped telephone taps in which a caller discussed with Pilarinos that “the stage” had to be returned to the Palace in time for that night. The man then mentioned strippers with “snakes”.

It was clear the caller must have been at the police party. Which meant he was a cop or someone closely linked to the force.

McCulloch suddenly realised he knew the other voice. It was Kevin Hicks, a former major crime detective who’d switched to running the drug squad property office.

The lazy, overweight Hicks was originally from Benalla in northeast Victoria. This was clearly the man referred to as “the fat boy from up north.”

Every “fat boy” reference on the telephone taps meant Hicks. McCulloch felt sick at the betrayal. Not just angry but nervous.

“Hicks had been coming up to me and asking about my operation,” he would say later.

“I was chuffed that such an experienced detective was showing such an interest in my job.”

Hicks’ transfer to the drug squad had been an odd appointment, as he was notorious in the crime squads for stealing money, drugs, guns or anything not nailed down while on raids. McCulloch found he was such a habitual thief that fellow major crime detectives had deliberately left him out of raids.

But the force, like the Catholic Church and other institutions hiding sex offenders, routinely covered up its evildoers.

This was the reality of the Brotherhood’s code of silence: many police had dirt on many others, and those that stood apart from the rorters were too intimidated to object or too cynical to care.

Putting Hicks in charge of drug storage was the fox guarding the henhouse. It raised the question of whether some senior officer wanted him there.

The drug squad property store was a treasure trove of seized drugs and precursor materials. Once chemicals had been forensically tested for court, substituting them for lookalike materials was a temptation to make easy money that Hicks (and others) could not resist.

It was easy to match valuable drugs and chemicals with cheap and harmless substitutes. For years, Hicks set up burglaries at the property storage building at Attwood, a quiet area shared with dog squad kennels and police horse paddocks.

The storage was high-security and hard to get into — unless you had the keys. Hicks did, and “rented” them to Pilarinos and his speed cook James Sweetin and others. The crooks would replace stolen chemicals with lookalike materials, including tile grout and Coca Cola.

Hicks, popular with other boozy cops but lazy, had moved to the drug squad after a 10-year spell in the major crime squad. His new job let him wander the drug squad, chatting to detectives about assignments.

McCulloch, friendly and trusting, had often talked to the crime squad veteran, assuming he was trustworthy and helpful.

But the more McCulloch thought about it, the more clear it was that Hicks was selling out investigations. Strange things now made sense, such as the fact that a photograph of Pilarinos taped to his office wall had vanished.

It was likely Hicks had seen his Pilarinos file and relayed key facts to the crooks. McCulloch realised now why he’d found only the one clue in Pilarinos’s garbage despite repeated bin raids: after that first time, Hicks had warned the nightclub king.

The treachery left McCulloch feeling powerless — and vulnerable. Even more so after making what he thought was a discreet approach to the police internal investigations unit.

Any hope they would run a genuine investigation was smashed when they avoided a proper interview, instead asking him to type his own affidavits in his drug squad office.

“You’re kidding!” he said to the two nervous “investigators” who met him in a car in an alley off Russell St. They weren’t.

It got worse. The story leaked immediately. Not to the media but to Hicks’s network of corrupt cops.

After a decade of catching crooks, the worst years of McCulloch’s life had begun.

That’s when he started drinking too much.

The drug squad was then housed in the old Russell St police station. It was supposedly a fort within a fort. To get in, you had to pass a security checkpoint then use special codes to enter the squad offices.

This stopped everyone except rogue police.

When McCulloch arrived the Monday after briefing the internal investigators, he used his pass to get in the building, took a lift, then punched in the code to the squad’s area.

But someone had beaten him. His office door hung off its hinges, jemmied with no effort to minimise damage. His filing cabinet had been forced. His Hicks affidavits were open on the desk.

Outside his office was a fresh dog dropping, a sign he was now condemned as a “dog”. A declaration of hatred, if not war.

McCulloch was so deeply shocked that, half a lifetime later, he still shakes his head as he describes it. He recalls stumbling like a zombie into the tea room — but that he couldn’t even make a coffee. His mind was frozen.

He had the choice of quitting and hiding. Or he could fight on, using every investigative trick he knew.

In a daze, he ran crime scene tape around his office. Then he called D-24 and said he wanted to report a break-in — at police headquarters. The telephone operator thought he was joking.

When a noticeably reluctant senior officer got there and took in the scene — dog excrement, broken door, opened files — he had the nerve to ask McCulloch if he was sure he hadn’t left his office that way himself.

The message was clear: you’re on your own, pal.

That’s how it went for the honest cop taking on city hall.

It got worse before it got better.

The crooks now knew about the telephone taps. They used that to set up a fake drug deal with a scripted conversation about dropping off “the white stuff.”

When McCulloch turned up to the rendezvous hoping to arrest Pilarinos, the “white stuff” was harmless white fabric.

The nightclub gangster was waiting for him. He laughed and openly gloated: “So you’re Lachlan McCulloch.”

The amphetamine sting was dead in the water. But McCulloch knew that the dozens of hours of existing telephone tapes contained evidence of other crimes. He pulled it all together and charged Pilarinos family members with serious offences, notably a conspiracy to cover up the truth about a car crash.

Pilarinos’s brother Jerry fell into the trap; he had been recorded plotting with his nephew, Peter Pilarinos junior, to commit perjury over the crash to make a false insurance claim of $35,000.

Jerry Pilarinos, Pilarinos junior and Valerie Pilarinos were all found guilty of perverting the course of justice in 1997.

And still McCulloch fought on.

Despite the death threats and the shunning and the sniping from rats in the police ranks, he eventually was able to persuade the “cook” James Sweetin to give evidence in a watertight case against Pilarinos, Hicks and their co-conspirators.

The shrewd Sweetin had kept “smoking gun” evidence that proved that Hicks had organised thefts of seized drug exhibits from the Attwood storage.

In 2000, eight years after his silent war began, Pilarinos and Hicks were jailed … both for eight years. McCulloch liked the symmetry of that.

The Pilarinos name later hit the headlines again when the Palace building was torched.

As for “the fat boy from up north”, the disgraced Hicks went from jail back to Lima East, near Benalla.

He was last known to be driving a courier van, making less money a week than he used to waste most days on restaurants, betting and top shelf booze.

Nailing Pilarinos and Hicks was McCulloch’s last police job. He left the force in late 1999 and has since worked as an investigator for various Government agencies. He was awarded the chief commissioner’s certificate in 2001.

It was over, except in his mind.

By coincidence he ran into a fellow former undercover officer in a pub much later and they shared some memories over a beer.

The other man asked: “Are there some jobs you shouldn’t have done?” McCulloch agreed there were “a couple”.

The other man said, “Me too.”

McCulloch was on the verge of tears but relieved, too. Someone else knew the damage done when you have to play a part as if your life depends on it.

“We were both injured in similar ways. I told him I left large chunks of myself at undercover meetings and I’ll never get those bits back. The wounds are permanent.”