Undercover Cop podcast: How Lachlan McCulloch risked it all

Every morning Lachlan McCulloch shed his identity to become another man and mix with some of Melbourne’s most dangerous people. The stakes were life and death. Listen to the podcast.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When the nightmare was over, the long-haired undercover cop went to a hairdresser’s and asked for a short buzz cut — then to have the stubble bleached white.

“A big change,” the hairdresser said.

“Exactly,” he answered. “To confuse the hit men.”

She laughed but he was deadly serious.

For too many months he’d been living a double life in which any slip could have got him killed. Facing that each day, he’d told himself he was invincible. Deep down, he knew he wasn’t.

Self-delusion was the biggest of the lies an undercover cop lives by. All he knew for sure was he’d never be quite the same again.

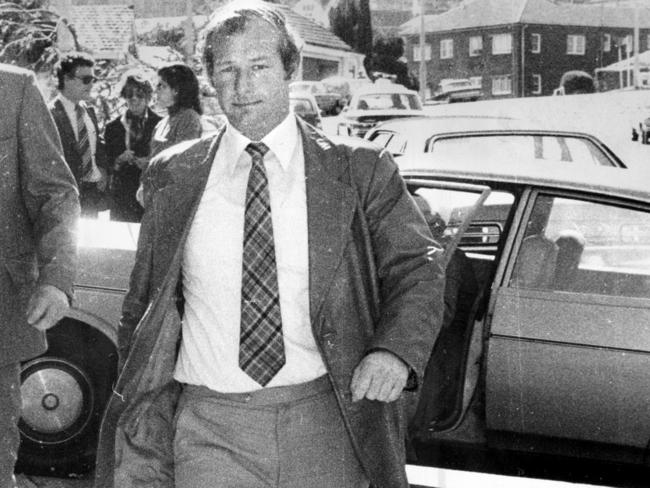

The sting was codenamed Operation Earthquake. The undercover was Lachlan McCulloch, Victoria Police’s “covert operative number 004.” It wasn’t officially a licence to kill — but it could certainly get him killed, and almost did.

After surviving the most dangerous assignment of his career, McCulloch didn’t know if he was a hero or just paid to pretend to befriend people then betray them.

He’d put his life on the line and jeopardised others to jail 16 criminals for a total 40 years.

His story is sometimes funny, often terrifying and as detailed as the official secrets Act allows.

“I found it a constant battle to remember who I really was, what my true feelings and true morals were. For a time I think I lost ‘me’ … I spent so much time being other people, none of them good.

“I would never advise anyone to work undercover the way I did. As a manager, I would never allow me to do what I did. It’s too dangerous physically — and way too dangerous mentally.”

Lachlan McCulloch had been in the force eight years when he vanished. The same week, a wannabe drug dealer appeared on the other side of town, calling himself Lenny Rogers.

There had once been a real Lenny Rogers, one of hundreds of people McCulloch brushed against as a cop.

The real Lenny was just another drug user. But, for a while, the detective had the job of listening to taped telephone calls he made.

Something about the Rogers name appealed to McCulloch’s chameleon streak: it rolled off the tongue and was simple without being too common. He saved it until the time came to invent a character.

The fake Lenny, the one McCulloch built, took shape after he noticed a cocky, cool-looking guy in black Levis and long bikie boots, a big belt and long-sleeve black T-shirt.

The man in black was stepping off his train in Prahran. McCulloch jumped off and followed him for an hour.

The stranger was not like the usual 9-to-5 workers. He had an edgy rock 'n' roll look, like a drummer or a roadie. McCulloch shadowed him and studied his swaggering slouch, his poise and mannerisms. Here was the model for his invented Lenny Rogers, a “yuppie” drug dealer making underworld connections so he could supply buyers in his own social circle.

That’s how Operation Earthquake started. For seven months without a haircut, McCulloch turned into Lenny Rogers every morning. As a trained operative, he’d parked his own identity to become another man, not just the clothes but the walk and the talk.

The stakes were life and death. It took more than mimicry.

“I’d played other street characters before and I’d thought of it as acting — but this was too heavy for acting. I had to turn myself into Lenny Rogers.”

To pull it off, he had to become someone he thought he wasn’t. Beyond the terrifying physical danger was something he’d never thought about before: the transformation corrupted his own “nice guy” character to fit with the underworld.

This was a sort of self-harm. But it was the only way to pull off the con needed to infiltrate one of the most notoriously wary criminal families, the one behind the Walsh St murders of two young policemen.

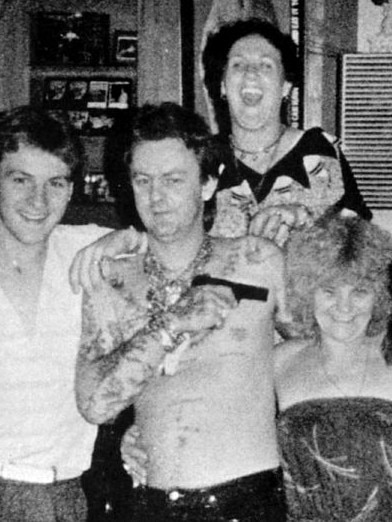

He got to know Kath Pettingill, matriarch of the clan, the granny who minded grandkids while dealing drugs. He befriended one of her six sons, Trevor Pettingill, drug trafficker and suspected cop killer. Through them, he reached a tight network of their associates: heavy traffickers, robbers and killers.

For those months, as “Lenny” bought drugs and lived with constant fear, Lachlan’s family and friends worried about the change in him.

He drank hard, swore hard and became hard, far from the cheerful Lachlan they knew. He gained the nervy alertness that shrinks call “hypervigilance.”

He rarely spoke frankly about it but once admitted: “I felt like a zebra walking into a lion’s den having to convince the lion I wasn’t a zebra at all.”

His family saw the change in him and feared that by fighting monsters he might become one himself.

The role consumed him. At night, he shed the “Lenny Rogers” gear on the porch and took a long shower before he saw his family. But he couldn’t forget the frightening things he’d seen and done, or drown the fears buried inside.

It happened in 1993. A woman McCulloch calls “Fran” to protect her identity, whose husband was serving time for armed robbery, had moved into a house in Rowville in Melbourne’s outer east.

Kath Pettingill was living across the street in a house owned by her killer son Victor Peirce and his wife, Wendy. While the Peirces were in jail, Kath was looking after their children.

Kath almost trusted Fran because they had been in jail together when Fran did time for shooting up a paedophile’s house. Fran trusted “Lenny”, although she knew he was an undercover policeman.

Fran’s motive to help was that she hated hard drugs, the “powders” she blamed for her husband’s crimes.

The Lenny Rogers “yuppie drug dealer” persona was a shrewd compromise with reality. “That’s what I am,” McCulloch explains.

“I’m not tough. I haven’t got a broken nose or tatts and haven’t been to jail, so why pretend and get caught out?”

He played a lover, not a fighter. He turned up at Fran’s at all hours and pretended to spend nights with her — leaving late in the morning so that Kath saw him drive off. Through Fran, he began making small drug buys from Kath. But the cagey Granny Evil wouldn’t meet him because she’d never heard of Lenny Rogers.

“In her eyes, I was a nobody. I hadn’t been in jail. Had no form.”

The stand-off went on for weeks. Kath wouldn’t trust anyone. When Fran handed her $2000 from Lenny for “speed”, she took it but stalled on providing the drugs.

After he acted upset to force the issue, Kath growled, “Right, I want Lenny’s full name and address and date of birthright now.”

Phone taps revealed she called the corrupt former Sydney detective Roger Rogerson, who ran a check on Lenny Rogers and reported back that although Rogers seemed to be a real person, he had never been in jail and had no form.

McCulloch: “I made sure I was home when Kath came over one day and walked in on me. I didn’t say a word. I hadn’t met her. I was in the lounge room and she walked straight out after seeing me. She went up to Fran and said, ‘How f...in’ dare you have this bloke around.’ Fran just laughed. She said, ‘He’s my man. I know who he is.’

“She was loud, the queen of the criminals,” McCulloch recalls. “She scared hell out of me.”

He was also worried about something else. Would Kath remember a rookie cop opening the door for her at Richmond police station nine years earlier? That had been him, fresh from the academy.

He’d warned Fran that if anyone said they knew his face, tell them he’d been a child actor in a 1970s television commercial.

One day, Kath decided Lenny was okay. She told him about her son Dennis “Mr Death” Allen and pointed to the chunky gold chains she’d taken from Dennis as he died.

It was so nerve-racking, he could hardly speak but Kath didn’t notice. That night, she delivered a stash of high-grade cannabis and the deadly dance had begun.

Lenny said he wanted heroin and offered to pay $12,000 for a pure ounce. Kath, alert to police bugs, kept referring to heroin as “a slow car”. Lenny needed concrete evidence. He was “wired for sound,” praying Kath wouldn’t search him.

“Slow car?” he asked. “You mean smack?”

She nodded and said “Yeah”. Then realised she’d made an admission.

“She leapt and grabbed my chest and patted me down and then screamed, ‘Strip! take your f...in’ clothes off now!’”

He took off his pants but, before Kath made him remove the shirt covering the recording gear, the quick-thinking Fran reached over and grabbed his genitals.

Fran turned to Kath and smiled and said: “Don’t search that — that’s mine.”

Kath was enraged. “Do you think this is a joke? Do you think we’re playing f...in’ games? This is business!”

That intervention saved the day, possibly his life. In her anger, Kath forgot about the rest of the strip search and the wire went undiscovered.

Worse was ahead. To clinch the drug deal, Lenny had to meet a man who scared everyone. His name was Steve McKinnon, but he was known as “Stacker” for macabre reasons.

The homicide squad had interviewed Stacker several times over bodies outside his flat, people killed with “hot shots”, deliberate heroin overdoses.

His nickname came from the story he’d once stacked one body on top of another then called the police to complain about corpses littering the building.

The day came to do the deal with Stacker.

“Lenny”, Fran and another woman sat in a car in Collingwood, waiting. When Stacker got in, he was livid. He had just seen someone taking photographs near Trevor Pettingill’s nearby flat.

“He went ballistic,” McCulloch recalls.

“He jumped in my car and we drove off at a million miles an hour around the backstreets. He’s saying, ‘I’m not happy ... Kath’s not going to be happy. You’ve f...ed it up’.”

They drove to Yarraville rail station. Stacker demanded the cash, saying he’d take it around the corner, get the heroin from his supplier and bring it back.

Lenny stalled. He wasn’t letting the money go without getting the heroin. He feared a rip-off. Stacker spewed threats, revealed a pistol under his jacket and started scratching his index finger and saying “This finger is ... getting ... very ... itchy.”

The women were scared. One screamed, “Just give him the money, he’s got a gun’!”

But “Lenny” had one too, under his shirt. He had it pointed at Stacker and wondered how many shots it would take. The standoff lasted two excruciating hours.

Stacker pounded a bottle into his hand, as if ready to smash it into Lenny’s face. His heroin supplier walked around the corner then hurried off. He had seen suspicious people in the area — cops posing as passers-by.

Stacker got out and spoke to his spooked supplier. The deal was off.

Angry words reached Kath that Lenny must be an undercover or some sort of informer. Phone taps picked up conversations between Kath and other crooks discussing it. One suggested setting Lenny up in a deal so a gunman could ride past on a motorbike, shoot him, take the money and escape before other police arrived.

Lenny lay low for a week. Then, unbelievably, he set up another meeting with the people who’d been discussing whether to kill him. He apologised for bringing the police down on them. He said they must have been watching him and he hadn’t realised.

It amazed him how he could play to the crooks’ greed. They were street savvy and paranoid but, when it came to money, they often ignored their doubts.

Which was why, a year later, Steve “Stacker” McKinnon, Kath and Trevor Pettingill and three others went to jail for dealing heroin, convicted on the evidence of “Lenny” McCulloch, Fran, and her friend, Sally.

“Lenny” lived to tell the undercover’s tale, but the man behind the mask carried invisible wounds. He’d come within a whisker of death because of other police’s stupidity.

It had happened when he was taking $50,000 cash to pay Trevor Pettingill for heroin. During the previous deal he’d felt caught out when Pettingill picked up a wad of cash and asked how much it was and he hadn’t known for sure.

He hadn’t wanted that to happen again. So he pulled over and counted the cash in each bundle on the way to do the deal.

It probably saved his life. On one wad was a yellow post-it note printed with the words OPERATION EARTHQUAKE, TARGET TREVOR PETTINGILL.

A death sentence, courtesy of a lazy fellow cop.

That was the moment of truth for McCulloch. And the stuff of recurring nightmares.

“I realised that no matter what I did, other people could get me killed in a heartbeat. That broke something in me. After that I knew I had to stop.”

Eventually he did stop. But the damage was done.