Undercover Cop podcast: Surviving and thriving in 1980s St Kilda cesspit

St Kilda in the 1980s was littered with the addicted, desperate, predatory and preyed-upon — it was the perfect place for an undercover cop to make his name. Listen to the new podcast.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The young Lachlan McCulloch had hardly met a police officer, let alone a crook, when he left Mentone Boys Grammar as a teenager.

He was a naive, middle-class kid with no ambition except to slip the well-padded handcuffs of a comfortable life.

His parents bought him a return ticket to Europe but he overheard his father predicting he wouldn’t cope with looking after himself for long. He proved that wrong, staying away a year and working a series of jobs from tennis coach to barman.

It gave him perspective and a taste for swimming outside the flags. When he got back to Melbourne he found the same friends taking out the same girls to the same parties. It seemed boring and predictable to a restless youngster who liked the outdoor life.

He drifted from casual job to job for a couple of years. That changed when he went to a fancy dress party in Carlton and met a homicide detective dressed as a Clint Eastwood spaghetti western outlaw.

Lachlan asked what it was like being a cop and never forgot the answer.

“He said it was just fantastic. He drove fast cars, caught crooks and just generally had a ball. I was hooked.”

Young McCulloch had never been a good student. His main skills were playing tennis and fishing, both to a good standard. Those two disciplines had taught him the value of preparation, practice and patience.

He had to be cunning enough to get through the police academy, as so many didn’t. So he enrolled in a short course that promised to teach how to pass the police entrance exam. It did, just.

He walked into the Victoria Police Academy on January 4, 1984. Five months later, he graduated in 39th spot of a squad of 41.

“Not a brilliant start,” he said later. “A sign that as a copper I was a bit different from most of the others.”

He was. At his 30th birthday seven years later he would have 60 guests. Only one was a cop. That was Darren O’Loughlin, part of a famous police family and who had also been a bored and carefree youngster before signing up.

The pair had forged their friendship in St Kilda when it was the most lawless police “patch” south of Kings Cross: the place where Lachlan learned the skills that would make him an outstanding undercover investigator — but never really “one of the boys”.

Mild-mannered, polite and relatively slightly-built, he was never the beefy cop most people then expected to see in uniform or the cheap suits that detectives wore in those days.

“My whole demeanour was not one of a typical cop, so I didn’t really fit in. Typical arrogant cops had no idea where I was coming from. I didn’t play football and go to the pub with them after work. In many ways, I was a bit of an outsider.”

But he wanted to be at St Kilda because that’s where the crooks were. He’d soon prove he could catch them.

He noticed that crooks casually cultivated cops by buying them drinks or getting them “drink cards” at nightclubs.

He noticed that crooks didn’t like cops who paid for their own drinks, or even insisted on shouting for the crooks. Cops who couldn’t be compromised with free sex at brothels or with free or “discount” jewellery, watches or electrical goods.

Maintaining boundaries made an honest cop dangerously unpredictable to criminals. But in those days, in that place, not many maintained the boundaries. McCulloch did, and that marked him as different.

Rookies weren’t allowed to go straight to St Kilda from the academy so he started at Richmond, then a tough inner suburb that harboured Kath “Granny Evil” Pettingill’s clan: Dennis and Peter Allen, Victor Peirce and Trevor Pettingill and their hangers-on.

Led by Dennis “Mr Death” Allen, the clan dealt huge amounts of heroin from a rats’ nest of shabby houses and brothels in the Cremorne drug triangle bounded by the Yarra, Punt Rd and the railway line from South Yarra to Richmond Station.

In his first week at Richmond, Lachlan saw a middle-aged woman outside the police station and politely opened the door for her.

She looked at him and snarled “What the f*** do you think you’re doing?” and then called out to several amused police inside to have a look at the (expletive deleted) idiot holding the door open for her.

She then walked inside and signed the bail book — on charges of heroin trafficking and possessing a machine gun. That was his first brush with crime matriarch Kath Pettingill.

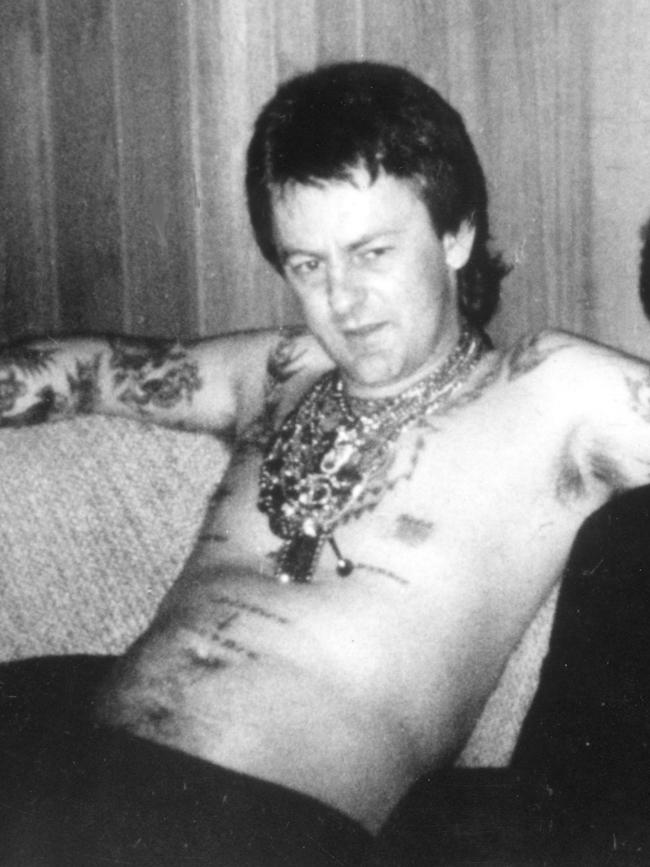

Nine years later he’d meet her again in very different circumstances. By then, he was no longer the fresh faced rookie in uniform, but dressed like a rock and roll animal and using an alias … Lenny Rogers.

Kath didn’t remember his face but he knew hers very well. She and her sons and their crew were the target of Operation Earthquake, which would lead to putting Kath Pettingill and 15 others behind bars.

But the great Pettingill sting was later. A lot of things happened to young McCulloch before that. His tour of duty in St Kilda, for a start.

They called it “the St Kilda police force”, as if the red light district and drug market by the bay was a separate jurisdiction from the rest of Australia. Which, in a way, it was.

Like King’s Cross in Sydney and Soho in London and the old Times Square in New York, 1980s St Kilda never slept because the addicted, the desperate, the predatory and the preyed-upon flocked there from across the wider city and the state, not so much bees to honey as flies to corruption.

Richmond had already taught McCulloch a lot about the damage done by drugs: 20-somethings looking 40, faces haggard from feeding an addiction that would kill many. And St Kilda was where many of them ended up, one stop from the grave. It was where hopes and dreams came to die, often violently.

McCulloch started on general duties, everything from watch-house duty, patrolling in cars or divvy vans, handling warrants and files. But every time he was on Fitzroy St, he talked to the passing parade of burglars, prostitutes, street dealers and users.

After a year he was picked as a full-time plainclothes member to work alongside detectives.

He made the most of it by asking everyone he arrested about their world, about how and why they did the things they did. The thing was, many of them told him. As taxi drivers and hair dressers know, most people just need an audience.

“One thing I knew how to do before I started in the job was to catch fish,” McCulloch would recall.

“To catch a certain type of fish you have to understand where they would be at certain times and why they would be there. That way you could use the right bait and tackle to catch them.”

The fisherman of Fitzroy St realised that no matter how stupid, reckless or drug-affected his catch was, they were oddly proud of their “achievements.” Most were prepared to brag if encouraged.

Instead of asking crooks all about the burglary they’d been arrested for, he would ask why they hadn’t burgled any one of hundreds of other houses. Similarly with stolen cars. Why that one and not others?

“Everything I heard first hand told me I had to stop thinking like a copper and start thinking like a crook.”

Working undercover started with a grey cotton jacket he wanted to be his trademark in the street. So that when every hooker and dealer and thief was watching for the plainclothes cop in the grey jacket, he could take it off, change his shirt, add sunglasses and become truly anonymous.

He knew he’d made the grade one day when he entered the Prince of Wales hotel and the trans bartender assumed he was a stranger and warned, “Be careful, there’s an absolute prick of a copper out and about. You’ll know him, he’s wearing a grey jacket.”

Not long after, he was selected to work in plain clothes full time, which led to so many arrests he was fast-tracked to becoming a detective. It was the start of a swift rise for the battler who’d barely scraped through the academy.

The process of becoming a detective meant an interview with a board of senior officers which meant getting a regulation haircut. This interfered with working undercover at a time when only police and military had short hair.

So he bought a long, light brown wig and dirtied it with fat, and used the Marlon Brando trick of wadding tissue paper in his cheeks to change his face.

“I got an old green fishing jacket, stupid pants that were too big and worn-out snow boots and a floppy jumper, topped off with an old canvas bag filled with empty bottles.”

The idea was to look like a loser a step away from the gutter. One day he tested the disguise around the police station, and was lucky not to be thrown in the cells for supposedly attempting to break into police cars. Two police he’d worked with for months looked at the grubby intruder with disgust but without a flicker of recognition.

Even after he spat out the paper wads and pulled off the wig, the other police took several seconds to recognise him.

McCulloch thought the dirty wig made him look like a long-haired dog, a collie.

And so Dean Collie was born. “Dean” started out doing surveillance on the street, then buying heroin — often from the same dealers McCulloch had arrested in the past.

Not one of them recognised him. That’s when he realised he had the makings of an undercover operative.

What he didn’t know yet was that it was a dangerous skill to be cursed with. One that would lead to a showdown with deadly enemies on both sides of the law.