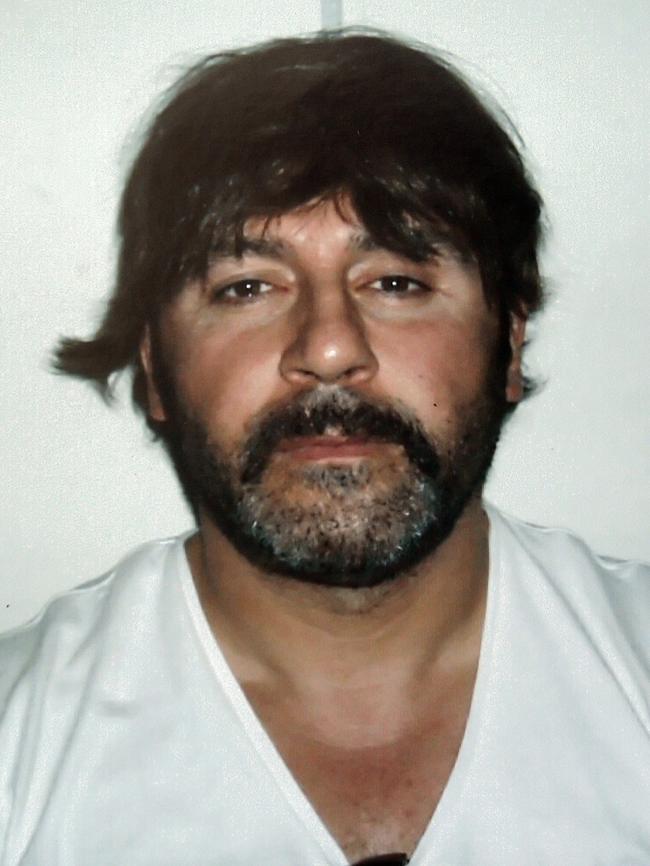

Tony Mokbel bounded into the Supreme Court as though his charcoal jacket was lined with cheap watches and the dock was his Bali beach. Everyone was his mate — the journalist he clapped on the back, the lawyer who got a wave. He greeted a cop in Lebanese. The cop replied just as amiably — in Greek.

Mokbel was always making deals — it didn’t matter if it was drugs, properties or life sentences.

The underworld boss was known for red ties and multiple phones, lending him the slick bearing of mobile phone salesmen of the era. Among his many contacts was a lawyer who never seemed very lawyerly.

PART 3: THE MAN IN THE GOLDEN COFFIN

PART 8: HOW WE UNCOVERED THE TRUTH

Nicola Gobbo had given him advice in June 2007 when the bewigged fugitive was flushed out on the other side of the world and locked up in a Greek cell — he had made a deal to get a mobile phone so he could ring Victoria Police.

She said he should try and make a deal with them.

Mokbel had been hiding out in Athens since jumping bail in Melbourne in March the previous year, while on trial for cocaine trafficking — sparking a global manhunt.

By July 2012, he was back in Melbourne and confronting the next few decades of his life in a prison cell. By then, all the deals were done.

As usual, Mokbel had struck another bargain.

As usual, his unofficial legal adviser, Gobbo, was cloaked from the public gaze.

He wore the impish smirk of someone who knows more than everyone else in the room.

His fleshy jowls and hooded eyes resembled the lead character in the Sopranos cast photos which turned up in Mokbel property seizures. His joviality seemed misplaced — as was the take of the police officer who lauded Mokbel’s “affability”.

Here was a suspected killer, throwing winks at members of the press, and looking happier than the man who was about to send him away for a minimum of 22 years.

Justice Simon Whelan held his face in his hands and contemplated a sentencing “minefield”. Mokbel’s behaviour on bail, the judge explained, was “just unbelievable”.

Mokbel’s then disappearance had prompted muddle-headed stories about priestly garbs, plastic surgery and gunfights in downtown Lebanon.

Mokbel made officialdom look silly, not because he was bad — which he was — but because he was so irrepressibly gumptious.

In heralding a new genre in wig jokes, Mokbel made almost everyone giggle when they shouldn’t. Justice Bill Gillard, who had chosen not to revoke Mokbel’s bail a few days before Mokbel skipped it in March 2006, later spoke about his career asterisk: “I have seen enough of Mokbel to know that he is a very engaging person; friendly, determined and cunning.”

Mokbel was also one of the biggest drug barons in Australia’s history.

He was unrepentant about the coke importation charges that earned him nine years, and the ecstasy and methamphetamine charges he had pleaded guilty to.

Jail stretches and police disruptions for him were like droughts for farmers or injuries for sportsmen: an unfortunate but accepted way of life.

He fought his charges on technicalities, despite an agreement to drop eight other drug charges, and never mind how his backyard meth lab exploded in 1997.

It didn’t matter that he was semiliterate and that he had led the so-called Tracksuit Gang in racetrack plunges.

Or that Justice Betty King, in sentencing, had declared Mokbel responsible “for one of the worst type of murders that may be seen” — after all, she was sentencing someone else (Carl Williams) at the time.

Mokbel applied charisma and what was called an “aura of immunity” to his work, whether it was the three tonnes of hashish he attempted to import in 2001, or the Ferrari number plates in a nod to police surveillance: R U DARE.

WHAT WAS THE GANGLAND WAR ALL ABOUT?

The tale of Mokbel’s capture in Athens is well documented.

Police relied upon an informer, known as 3030, from within Mokbel’s syndicate called The Company, for phone bugs that pinpointed his whereabouts. Here was a fable in hard yakka, hunches and punchlines.

“Brilliant work,” an impressed Mokbel told the police as he was escorted from a Greek restaurant.

What’s fuzzier are the identities of those who helped in Mokbel’s escape. Dawn raids produced arrests in 2008 — among them a couple believed to have housed him for a couple of nights in central Victoria in what they described as coerced hospitality. The pensioners, charged with perverting the course of justice, were numbers nine and 10 in the hunt to prosecute those who had helped Mokbel.

Detective Sergeant Jim Coghlan described the arrests as “the last piece in the puzzle”. But were they?

What seems strange is that no one was made accountable for alerting Mokbel to the murder charges that were to be brought against him, prompting his disappearance after a weekend walk at South Yarra’s Tan track.

For Mokbel — who was about to be found guilty on cocaine importation charges — was tipped off. Police said so at the time. And Mokbel says so now.

The odd thing is that the police version and Mokbel’s take do not gel. Strange, too, that police have never been seen to pursue the matter.

At the time, lawyer Zarah Garde-Wilson was blamed.

Australian Federal Police agent Jarrod Ragg named Garde-Wilson in a statement to the Supreme Court.

Garde-Wilson, who had been Mokbel’s lawyer, had also been the partner of slain killer Lewis Caine.

Her friendships and clients blurred in convenient conflation for authorities.

DANIELLE MCGUIRE: MOBSTER’S MUSE

Garde-Wilson was easy to vilify.

In part for her daring wardrobe choices, in part for her open defiance for authority. Vulnerable and lonely, went one line, a country lass manipulated by criminals. Another had her as the manipulator, corrupted and disrespectful of convention.

She was neither, Garde-Wilson now says. She defies the perceptions of the gangland days. A mother of three, she is demure and thoughtful over antipasto in a city restaurant.

Her “happy shoes” — floral high heels — are a lone show of extravagance. Otherwise, she no longer seeks to stand out from the crowd.

She had lunch with Mokbel two weeks before he disappeared, she says. But she did not tip him off.

The irony is that the woman who Mokbel himself now claims told him to “f**k off” overseas is described in the polarising extremes that Garde-Wilson attracted at the time. They fell out, and Garde-Wilson does not abide comparisons with that woman, Gobbo.

Garde-Wilson knew about the police statement implicating Mokbel in murder.

Many legal insiders did.

It first surfaced in early 2006, after a shooter had pleaded guilty to a South Yarra killing.

A police bug in his getaway car recorded faint gunshots, then the shooter’s return to the vehicle. “Get in, get in, get down,” the driver told him.

The driver had already rolled (his information on multiple gangland executions would lead to the murder convictions of Carl Williams). Phone taps recorded the shooter’s phone message to Williams after the hit, and his clumsy reference to a “horse scratching”.

By the time of his sentence plea hearing, the shooter, now known as The Runner, had offered a full confession about the ghastly assassination of Michael Marshall, a hot dog vendor and drug dealer, outside his home in October 2003:

“I am not sure how many shots I fired; I think it may have been three or four. Marshall started to fall to the ground and I think I fired one more shot into his head as he was going down towards my feet. At no stage during the altercation did I see or realise that Marshall’s son was still with him.”

Marshall’s boy, who was five, ran home to his mother.

In the statement, The Runner said Mokbel was upset by the recent killing of a lollipop salesman and drug dealer, Willie Thompson, who had been a friend from school.

Mokbel blamed Marshall, even though The Runner believed at the time that Williams had had Thompson killed.

“I was surprised that Tony didn’t really know what had happened,” he said.

The Runner said that Mokbel agreed to pay $300,000 for the Marshall hit at a meeting at a Brunswick Red Rooster. A meeting between The Runner, Williams and Mokbel was observed by police at that location.

After his arrest for the shooting, The Runner met with Gobbo, his then lawyer. He says he asked her to pass a message to Williams — could his hit fee please be paid to his mother? That The Runner’s mother was only paid $1500 drove his decision to inform against Williams and Mokbel, he explained.

The Runner’s statement, according to other court documents, was dated to mid-March 2006. In sentencing The Runner, the judge alluded to imminent charges relating to the same murder. It was someone big, up the chain of command from The Runner. Someone who was not currently in jail.

It appeared clear, say observers, that the judge was referring to Mokbel.

Justice Gillard, who in March 2006, was hearing Mokbel’s cocaine case, would be very specific about timing. Mokbel was believed to have been made aware of The Runner’s statement on March 14, five days before Mokbel politely checked in to South Melbourne police as per his bail conditions — for the last time.

Mokbel now says, in the words of an intermediary, that Gobbo had tipped him off to flee. A police officer told the Herald Sun in 2007 that Mokbel appeared concerned nearing the end of his cocaine trial.

“He was one very worried man when he spoke to me,” the officer said.

“He absconded because she told him to,” another source close to Mokbel now says of Gobbo.

“ ‘If you hang around you’re going to be arrested for a whole lot of murders’, she told him. “ ‘You might want to think about getting out of the country’.”

If Gobbo did warn Mokbel, it would have blindsided her police handlers, as she was a registered informer at the time.

Who was she trying to help — the law or the criminals? Those who knew her well answer “neither” to that question. Gobbo was always helping herself; she liked to please both sides and liked to be in control.

Gobbo would later claim her sole motivation to turn informer was in fact to “rid herself of the Mokbels”, to get the “Mokbel monkey” off her back.

“My breaking point came when I was threatened by Tony Mokbel to ensure that a first-time offender who was operating pill presses and manufacturing tens of thousands of MDMA pills for him, kept his mouth shut and pleaded guilty after he was arrested,” she said in a court document made public only this week.

“Although Mokbel did not actually say that his underling was being financed and supplied by him, it became obvious to me when I was provided with a remand summary and later a brief of evidence by Police.”

She would also go on to claim that Mokbel’s brothers Milad and Horty were among her greatest scalps.

Tony Mokbel didn’t heed all of the alleged advice he got from Gobbo.

For seven months, anyway.

Instead, he bunkered in a weatherboard cottage in Bonnie Doon, for walks and special deliveries, such as then girlfriend, Danielle McGuire. He was running The Company from there — as he would from Athens — for about four months when Justice Betty King labelled him a murderer.

King was sentencing Williams for the Marshall killing.

“What is now clear is that the murder was not done at your initial instigation, but that of Tony Mokbel,” she said.

Indeed, Mokbel’s role was “higher” than Williams’, who received a 21-year sentence.

Williams would later claim, in a novel piece of courtroom theatre, that he had no knowledge of Mokbel’s involvement in either death.

His performance would be derided as “mendacious”, “arrogant” and “not credible” by police and prosecutors in court. King called him “incapable of telling the truth”.

Gobbo and Mokbel became neighbours in about 2003.

She moved in next door at a Beacon Cove apartment block. Observers wondered why she chose to be so close to Mokbel.

Gobbo had first offered her legal services in 2001, when he was in prison. It’s unusual for a lawyer to hawk for business, but in this case it was productive: by the following year, Australia’s best known drug dealer was Gobbo’s biggest client.

For Garde-Wilson, being on Mokbel’s team meant “getting in” with Gobbo. This was tricky, because Garde-Wilson “couldn’t stand her”.

“She wasn’t anybody in the scheme of things until she approached Tony,” Garde-Wilson says.

Every visit to court that didn’t go Mokbel’s way invariably inspired an appeal.

Mokbel always thought he could win his way. A friend and fellow prisoner at Barwon would write about Mokbel’s optimism after an unfavourable court ruling in 2009.

“He reckons everything went as planned,” Carl Williams wrote to his father, George.

“His (sic) happy with it, his (sic) delusional that bloke — and of the highest order.”

Mokbel and Gobbo kissed (chastely) after a successful bail application in 2002. Gobbo would advise Mokbel, according to him, unofficially for many years after, long after Williams wrote a letter in which he described her as an untrustworthy “dog”.

Mokbel, who had six phones, says that Gobbo spoke with him — through an intermediary — while he was in Greece. He was anxious to hear about the police investigation and was, according to one source, in “constant communication” with her. After his arrest, he says, she advised him about his extradition.

FOLLOW ALL THE TWISTS IN THE LAWYER X SCANDAL

She was talking to her police handlers at the same time, according to Supreme Court documents released on December 3.

Among her other clients was Mokbel’s drug cook, who considered her a friend, if not more — he would be grilled years later about a $35,000 diamond ring, a claim he would reject.

The cook was loose of money, and lips, and he trusted his lawyer — she would even babysit his children. How could he know that everything he told her was relayed to investigators who encouraged their informer to socialise with her clients? In her defence, she felt guilty each time she deceived him. Though she kept doing it, again and again and again.

In September, 2005, she told police the address of the cook’s drug lab in Coburg. He was a good candidate to “roll’ on Tony’s younger brother, Milad Mokbel, she told police.

In April the following year, she told the police of another drug lab. This information led to the cook’s arrest, along with other Mokbel associates. The cook’s testimony would be used to prosecute those associates. They are among the so-called “Secret Seven”, listed to Supreme Court documents, whose cases may be tainted because of Gobbo’s conflicted role as a defence lawyer and police informer.

Gobbo betrayed the cook’s confidences, yet at the same time, she helped organise his 40th birthday.

It was March, 2006, and the celebration would double as a last drinks for the Mokbel cronies she was helping to put away.

The Gobbo relationship matters because Mokbel is, in effect, pushing for another deal.

ESKY MURDER CARL GOT AWAY WITH

In 2012 Mokbel was sentenced to prison until he is 67.

Now 53, he retains his famed humour, sending cards that depict him in a boat, in reference to his voyage from Fremantle to Greece. Perhaps now, more than any other time in recent years, he has cause for cheer. For Mokbel is seeking to be out of jail in four or five years.

Mokbel is defiant that Gobbo’s status as both a police informer and his defence lawyer was a conflict of interest that undermines some of his convictions.

Gobbo’s clients extended to Mokbel’s men, some of whom turned on their boss in pursuit of a lighter sentence. There was the meth cook, faced with a sentence said to be as long as a “telephone number”, who turned against his boss.

Gobbo is said to have unofficially advised the cook to snitch in return for a lighter sentence. Others close to the situation say that such advice was reasonable, in his circumstances, but nevertheless fraught — given it conflicted with Mokbel’s best interests, and Gobbo appeared to be Mokbel’s confidant at the time.

There are suggestions that Gobbo was in a romantic relationship with the cook. He had been squeezed, according to the book Mokbelly, when police nabbed him building a meth lab in Strathmore. Purana taskforce officers displayed photos of his children when they brought him in. The point was obvious — he wouldn’t see them for a very long time unless he informed against Mokbel.

Gobbo scorned Purana taskforce members who skited about bringing down Mokbel. As she put it to a serving police officer: “I gave them everything.”

Mokbel is also said to claim that Gobbo attempted to arrange meetings between him and NSW criminal elements. Similarities exist between his claims and those being made in what is being treated as a kind of legal test case regarding Gobbo — an appeal by drug importer Rob Karam.

Mokbel was extradited from Greece on charges of murdering Lewis Moran and Michael Marshall. He would be found not guilty on the Moran count. The Marshall charge, the reason for his sudden exit, would be dropped before it reached trial, exposing the flimsiness of so many gangland convictions that relied on informer testimonies.

“If they’ve got a weak case, you’re better off going through the system,” says one gangland lawyer.

HITMAN TAKES HODSON SECRETS TO GRAVE

Garde-Wilson’s arrest on contempt charges doubled as a pageant.

“You’re kidding me,” she told officers who confronted her at her then Little Bourke St office and “perp-walked” her to the car.

Media photographers materialised when Garde-Wilson arrived at the St Kilda Rd police complex. Why not call and ask her to come down, as police usually do in nonviolent matters?

It’s a rhetorical question, and Garde-Wilson has an answer. The police wanted her shamed and disbarred. Garde-Wilson narrows the motivation — interference from a lawyer who rushed to her aid at the police station that day, Gobbo.

Garde-Wilson had asked questions of Gobbo’s advice to clients, and warned them that Gobbo acted oddly.

Only years later, on reading a 2014 Herald Sun story, did she grasp the depth of Gobbo’s strange behaviour.

“I was treading on toes,” Garde-Wilson says.

“I was giving the opposite advice to her. If you’ve got someone conflicting with your informer, you’re upsetting the apple cart.”

Before a courtroom crowded with detectives from Purana taskforce (the police unit set up to end the gangland war), Justice David Harper accepted her claim of “genuine fear” or, as she put it, getting “my head blown off” in sentencing her for contempt (conviction and no further penalty). The Director of Public Prosecutions unsuccessfully appealed the sentence to the High Court.

Garde-Wilson likens the official ill-will against her at the time to a vendetta, and she names names.

She felt most victimised, she says, when she was charged by the Australian Crime Commission for providing information from a psychic’s reading, because “spirits don’t exist”.

“Police liked arresting me,” Garde-Wilson says.

Yet as the named suspect in the tipping-off of Tony Mokbel, she was not interviewed about his fleeing the country. Nor, it seems, was anyone else, including Gobbo.

Gobbo has been accused of similar behaviour before. Roberta Williams tells a tale from 2004, not long before her ex-husband Carl was stopped in his car in Beaconsfield Parade, Port Melbourne, and locked away for the rest of his life.

Roberta Williams didn’t like Gobbo much, after the lawyer had stood on stage at her daughter Dhakota’s christening and assumed what Roberta felt was an undue presence.

Mokbel’s girlfriend, Danielle McGuire “hated” Gobbo, though Mokbel continued to confide in her.

“Everyone knew that (Gobbo) got information from police, the lawyers, the judges, whoever, and that information was always right,” Roberta has acknowledged.

So when Williams walked with Gobbo near the Supreme Court, and Roberta claims she told him he was going to be arrested, Williams believed her.

Williams, says Roberta, told her after the meeting: “ said that I should f**k off overseas.”

He went on: “I’m going to get pinched, what should I stay here for?”

Roberta convinced Williams to stay. She says she was unaware of the extent of his criminality at the time, and she argued that he had done nothing wrong.

Long afterwards, while serving 35 years for four murders, Williams told his ex-wife that he should have gone when he could.

By then, Roberta Williams agreed.

Which is why she says she still regrets her advice “every day”.

MORE CRIME:

DEATH STARE: CARL’S EVIL KILLER

‘I miss being able to talk to them’: Tribute for slain Aussie brothers

A tribute has been unveiled where Australian brothers Jake and Callum Robinson and their American friend were murdered during a surf trip.

Melb private schoolboy’s stunning Russian mafia admission

An investigation into former Melbourne private schoolboy Damien Carew has taken a dramatic turn after his latest police confession.