The night a sports star saw Carl Williams dump chopped up esky body at beach

A SPORTS star’s beach jaunt to Blairgowrie took a gruesome turn when his mate Carl Williams asked him to pop the car boot and grab him a drink from the esky. ANDREW RULE PODCAST

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JOCK “The Hammer” Black is not his real name.

But there are clues in it for those who know him. It’s the alias he has chosen to reveal an underworld murder few people left alive know much about.

Jock was sitting in Cicciolina’s Restaurant in St Kilda one Sunday night in the spring of 1999, when his mobile phone buzzed.

WHY DID WE FORGET THE TAPP MURDERS?

SPORT STAR WITNESS TO CARL’S FIRST KILLING

INSIDE AUSTRALIA”S BADDEST BIKIE GANG

The caller was Carl Williams, then a rising northern suburbs drug dealer still barely known outside his own circles, a situation that would alter dramatically in the following couple of years.

Jock wasn’t a criminal but knew plenty of them.

He was a professional athlete who’d known Williams since they had knocked around Broadmeadows as teenagers in the late 1980s.

SUBSCRIBE TO LIFE & CRIMES WITH ANDREW RULE PODCAST:

Jock’s first girlfriend had lived around the corner from the Williams family and he’d gotten to know Carl and his brother, Shane, who would later die of a heroin overdose.

‘‘I bought my first hot video player from Carl,’’ Jock recalls. ‘‘He was just a low life then, burgling houses.’’

Jock and the Williams brothers would play street cricket and swap tips on races, boxing and football. Williams liked Jock and owed him a favour.

One night, years before, Williams been ‘‘glassed’’ at Cramer’s Hotel in Preston and Jock had driven him to hospital.

Now, a decade on, they were in their late 20s and their idea of good times had overtaken street cricket and stolen video players.

Jock had left Melbourne several times and on his most recent return, he could see that chubby Carl “the burglar’’ now thought he was a gangster. He certainly spent as if he was, so when Williams called, Jock jumped at the chance for a night out.

“I was seduced by the dark side,” he admits.

SUBSCRIBE TO SUNDAY HERALD Sun LIFE & CRIMES ITUNES | RSS

No dinner and strippers this time

Williams told Jock he’d pick him up in 20 minutes. Jock thought they’d be going to Dome nightclub, down the road in South Yarra, to kick off an all-night session.

It was a fair assumption: they’d done it before. ‘‘Usually, we’d go to dinner first, then to the Men’s Gallery and grab a few strippers and it would be on.”

Jock finished his meal, paid and walked out the back door of the bar to wait in the car park, then a favourite meeting spot for St Kilda night crawlers. It was where Williams dropped off packets of ‘‘gear” most weeks to a hulking ‘‘trannie’’ who dealt drugs to other sex workers on that side of town.

It was about 9.45pm. A few minutes later, an anonymous, dark-coloured sedan pulled in. Williams was driving. He didn’t go for flashy cars when he was doing ‘‘business’’.

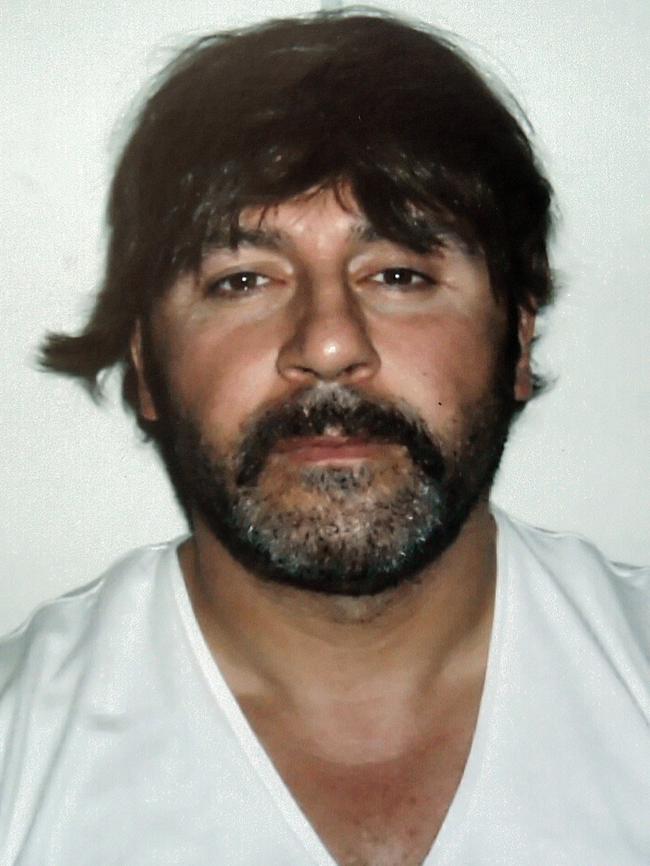

The car was riding low on the springs. Jock recognised Dino Dibra sitting beside Williams. Jock had met Dibra before. He got in the back seat next to a little, hard-looking man. It was Andrew ‘‘Benji’’ Veniamin, a sometime kickboxer not yet notorious outside his own patch of Sunshine.

When Williams drove into Acland St he turned left instead of right, heading east. Then he turned down the Nepean Highway away from the city.

Jock was surprised. ‘‘I thought it was going to be another night of debauchery at Dome, with strippers and cocaine,’’ he says.

“Going out with Carl was like going out with Caligula. I told him that once. He didn’t know who Caligula was but he liked it when I explained it.’’

As the sedan headed through the bayside suburbs, Jock grew curious. He didn’t want to seem nosy but as they passed Mordialloc he asked where they were going. ‘‘Carl just said something like he had ‘to see a bloke’.

“He used to look in the rear-view mirror and hold his finger up to his lips and point towards the roof to make sure we didn’t discuss anything in the car, so I didn’t say much. But when we went past Frankston I said, ‘How far are we going?’ and they just laughed.’’

As they passed through Rye, Williams slowed to read road signs. He was looking for Hughes Rd. He turned into it, and drove uphill towards the ocean side.

They stopped in the deserted car park overlooking Koonya Beach, one of the most treacherous spots on the Peninsula. A walking track ran from the car park into dense tea-tree and scrub.

Williams asked Jock to fetch a drink from ‘‘the Esky’’ in the boot.

MORE SUNDAY HERALD Sun:

UNDERWORLD BAIT LURED LES SAMBA

BOUTIQUE REBORN: GOSSIP QUEEN FIONA BYRNE

‘Hey, where’s me drink?’

As Jock opened the boot he saw it was lined with black plastic.

In it were two white tubs, the sort used at fish markets and abattoirs.

He lifted the lid of one tub but there were no cans of drink.

There was nothing but raw meat. For a moment, he thought they must have brought legs of lamb for some sort of midnight barbecue.

Then he saw the hand poking from the blood and broken bones.

JOCK felt sick. He swore at Williams, who laughed at him. ‘‘Carl said, ‘Hey, where’s me drink? You’re hopeless. I might as well as ask the bloke in the boot for it!’.”

They’d set him up. He wondered, later, if that was why they brought him … to have a laugh at his expense and turn the whole horror show into some sort of black joke. But behind the laughs was the tendency that often tripped up young crooks: to boast about the things they should keep secret. As if getting away with something didn’t really count unless someone else knew.

‘‘It was a day out for them,” Jock recalls. “Just a drive to the beach. They were joking about it. It was so bizarre.”

Williams motioned Jock away from the car to talk. Ever since he’d got out of jail on drug charges, Williams had been wary of listening devices and wouldn’t say anything incriminating anywhere near his car. Not yet, anyway.

(A couple of weeks after this night, Jason Moran would shoot Williams in the belly, igniting what became the “Gangland War”. Williams would grow reckless as he ordered hit after hit, believing his own boasts that he ‘‘ran the state’’. But that was later.)

For once the cheeky Jock was stumped. He watched Dibra and Veniamin get a torch and short-handled shovel from the boot, then hoist the tubs and carry them down the steps into the scrub.

They returned later without the tubs or shovel.

And on to the nightclub — without ‘D’

Williams drove back to Melbourne faster than on the trip down.

They were keen to hit the nightclubs and not so worried now about being pulled over by the police.

They went to a plush converted warehouse Williams was using, somewhere in Fitzroy or Carlton, to shower and change.

Jock was already in sharp clothes, not that they ever had any trouble from nightclub security. The bouncers on the door at Dome waved them past the queue.

Some time that night Williams told Jock the dead man’s name.

It didn’t mean much to him but he would remember it and that nightmarish night. Fifteen years later, when Dibra, Veniamin and Williams were dead — all murdered, ironically — Jock recalled it as a ‘‘Croatian’’ name, starting with D and ending in a ‘‘–vich’’ sound.

What jolted his memory in early 2014 was that police announced that a man not seen since 1999 was a missing person.

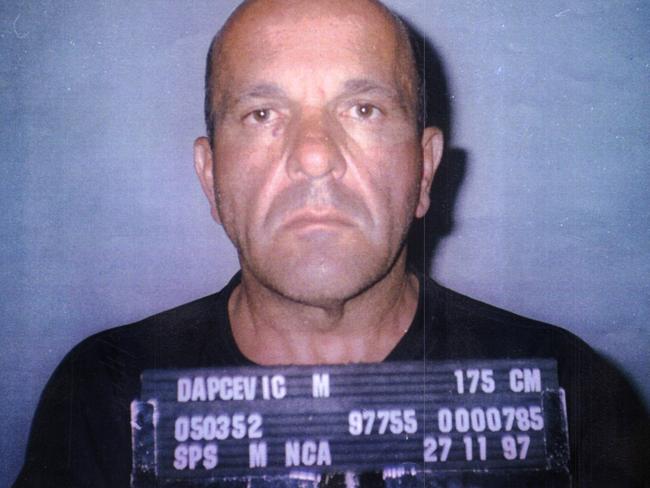

When Jock heard the missing man’s name, it hit him. He guessed he might be the only person alive who knew exactly what had happened to Milorad Dapcevic.

Who was the body in the boot?

THE strange thing about Dapcevic was that no one seemed to miss him. If anyone had wondered about his whereabouts, or his health, they hadn’t bothered telling police.

He had drifted apart from the few relatives he had in Australia, perhaps because, even at 47, he courted trouble. He had served time for violent crimes including armed robbery and still hadn’t pulled up.

Some associates no doubt suspected he’d left Australia for his family’s birthplace in Montenegro, presumably using a false passport. Normal checks would have revealed his movements if he had travelled using his own name.

Whether the theory that Dapcevic had bolted was a false trail or a reasonable conclusion, it gained enough strength to support a long-held police opinion that he’d probably fled for his own safety.

Investigators had reason to draw this conclusion, because they knew the missing man had made a police statement the last time he was seen in Melbourne. They would also discover that he faced drug charges interstate.

Jock knew of Dapcevic by reputation as an underworld figure but ‘‘under the radar’’. Dapcevic ran with ‘‘Jim’’, correct name Dimitrios Belias, a rogue member of a Greek family in the hotel business.

Belias was a fringe player who ducked and dived between the underworld and semi-legitimate business. He met shady people when his family ran the Fenwick Inn pub in Carlton and became a fast talker who could move anything from hot cars to fake gems.

He had connections in the used car trade, reputedly doing debt collections for one South Melbourne dealer, using a driver to take him from place to place. He was not regarded as a leg-breaker himself but sounded as if he knew one.

Belias was a smooth talker. He once persuaded the retired star jockey Roy Higgins to invest in a hotel in Cairns. “The Professor” was an artist in the saddle and shrewd in the mounting yard but a better judge of horses than of people.

The Cairns venture didn’t leave Higgins broke but came close. When he sent someone to Cairns under cover to check the hotel operation, he found that Belias and his crew were bleeding the business, skimming the tills and stealing stock. The pub was losing money but Belias and his cronies weren’t.

Belias’s form didn’t improve back in Melbourne, where he posed as a businessman but gravitated towards crime and criminals, one of them being Dapcevic.

The St Kilda Crew and Tony Mokbel

According to Jock, Dapcevic and Belias were part of a loose group he calls ‘‘the St Kilda crew’’, the sort of middlemen who dealt in drugs, stolen property and contraband.

Belias lived in Brighton; Dapcevic in nearby Elsternwick.

For some reason, by 1999 it seemed this “south of the river” faction had fallen out with Williams — or the real power behind Williams, Tony Mokbel.

At that stage Mokbel was unknown outside racing. He was regarded as the money man behind the ‘‘Tracksuit Gang’’, which co-ordinated massive betting plunges, a favoured way of laundering drug money.

Mokbel had cultivated two useful groups: racing people and kickboxing people.

The racing crowd included bookmakers, jockeys and trainers, including a later fashionable trainer who reputedly got his start growing hydroponic marijuana under a house near Flemington.

The kickboxing crew included the late Andrew Veniamin and the ‘‘friend” that Veniamin ended up killing, Dino Dibra, among others. Jock says it was a kickboxing connection who bought the cocaine in Mexico for the smuggling run that led to Mokbel’s downfall.

A boxing gym adopted by the kickboxing fraternity ran for years near the Queen Victoria market in the same building as a big car wholesale business. The car auctioneers knew the gym regulars, who used to borrow cars for ‘‘business’’ when they needed them.

This was the pool Jim Belias swam in, gambling that he could dodge the sharks further up the food chain. He was wrong.

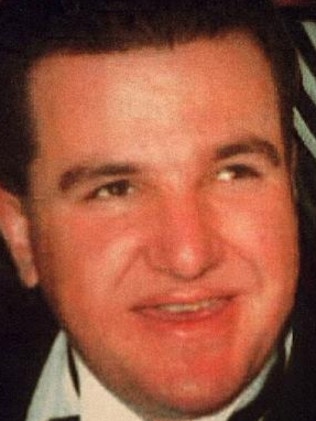

Dimitrios Belias meets his end

ON the afternoon of September 9, 1999, Belias and his driver Greg Smith had a drink at a Collingwood pub around 5pm after a day driving around on “business”. Belias mentioned he had to see someone in St Kilda Road at 7pm.

Smith was seen as more of a bodyguard than a friend to Belias. But as a minder he made a good driver.

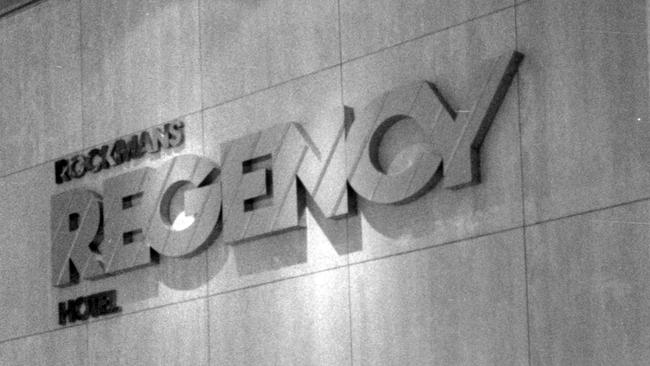

If Belias mentioned whom he was meeting or why, Smith forgot by the time he spoke to police. They parted about 5.15pm, when Belias drove himself into the city and parked outside Rockman’s Regency Hotel.

Here, at ‘‘approximately 5.47pm”, police would later note, Robert ‘‘Bluey Bob’’ Mather got into the car with Belias.

Mather, a self-employed entrepreneur known to some police as a likeable rogue and to others as a cunning career crook, naturally declined to make a statement about this. But conscientious police covertly recorded an unofficial conversation with Mather in which he said Belias had handed back a fake diamond (synthetic moissanite) that Mather had given him a week earlier.

Police would later find out that Belias had offered the ‘‘diamond’’ to several people in lieu of cash to settle debts.

He was a losing gambler juggling loan scams and skating on thin ice.

A police report would later suggest that Belias had substantial amounts of synthetic moissanite that was never recovered, which is a little mystery inside a bigger one.

The report continued: “The deceased’s movements after Robert Mather are unknown until approximately 6.50pm, when he was seen by a security guard sitting in his vehicle outside 594 St Kilda Road talking on his mobile phone. About ten minutes later, the security guard heard a loud bang, with the sound being heard by one of the contract cleaners, who subsequently found the body.”

Belias had been shot in the head as he stood in an underground car park. Homicide squad detectives interviewed more than 100 people. Few knew anything; most said nothing.

When Roy Higgins heard of Belias’s death he said it was well overdue — but that was an opinion, not a clue.

Nobody has seen Milorad Dapcevic since that week

Dapcevic was high on the police “To Do” list.

Five days after the ambush he made a statement.

It wasn’t until 15 years later, in early 2014, that police started checking up and realised there had been no sign of Dapcevic since he’d left St Kilda Road police station on September 14, 1999.

At that stage, police still guessed that Dapcevic had gone overseas, with one report suggesting he left the country in 2002. They believed he used a false passport or some other covert means.

But the police decided to probe more sinister possibilities. In a fresh investigation, divers scoured a stretch of the Yarra and found a handgun they sent for ballistic examination. More significant, perhaps, was spent ammunition found in a search of a property at Strath Creek, north of Melbourne.

An inquest did not find who killed Belias, only how it was done. The coroner found that he suffered a single gunshot wound to the back of his head, the bullet exiting through his forehead.

“The deceased … worked as a debt collector, although he was also involved in a number of illegitimate businesses that focused on gambling and loan scams,” the coroner wrote.

“He was a very heavy gambler with a past history of failed business ventures, association with underworld criminal figures and having criminal convictions for deception offences.”

It’s the kind of CV that earns enemies — maybe so many it’s hard to pick them apart. Police have checked over the people that Belias owed money and found nothing untoward. One of them is a man — for legal reasons — we’ll call Peter.

Who is ‘Peter’?

Peter had taken out a $150,000 life insurance policy on Belias’s life to cover at least the amount he was owed. When Belias was shot, other creditors got nothing but once the formalities were completed, Peter could claim against the policy.

Peter was a realist. He had once been sentenced to years in prison for drug trafficking and theft and he knew police would be obliged to check his story because he had what could be seen as a financial motive. He wasn’t fazed, and offered to answer any questions the homicide squad might have. He had an alibi proving he had been nowhere near the Belias shooting.

By horrifying coincidence, Peter was no stranger to the homicide interview rooms.

In 1984, when Peter was 27, tragedy struck him and his family. Starting in the evening of July 2, he worked all night. After finishing work at a pizza shop in Chapel Street, Prahran, he filled in for a friend on the door of the Hardware Club nightspot in the city until 5am.

Instead of driving home to Werribee, he slept at his parents’ house in Seddon.

When he got home later that day, July 3, he found a ghastly scene: his wife was dead in bed, with their son asleep in the next room. His wife had been shot behind the ear by an assassin who left no clues.

The killing had the chilling efficiency of a military operation. Now, police are linking it to Belias’s murder in 1999, to the shooting of a bodybuilder and bouncer, George Germanos, in an Armadale park in March, 2001 and a series of brazen heists with a total haul of up to $6 million.

If the dismembered body buried at Koonya Beach that spring night in 1999 was Milorad Dapcevic — which is the way to bet — it seems to add another murder to the list. Otherwise, it’s a startling coincidence that the body appeared so soon after Belias’s murder and that Dapcevic hasn’t been positively sighted since then.

All this poses questions.

If someone ordered Dapcevic’s murder, was it because they knew he’d made a police statement about Belias’s death? Or were they out to eliminate small-time crooks rash enough to short-change criminal heavyweights? Or, as some police still suspect, did Dapcevic just run away?

But if it’s not him buried at Koonya Beach, who was it?

Postscript: Police interviewed Dapcevic on September 14, a Tuesday. The dismembered body was buried on a Sunday night, probably September 19. Jock believes it had been kept in a Laverton factory used by Williams for several days before burial.

MORE ANDREW RULE:

WHEN BEANIE BANDIT THREATENED ME WITH BRICK