It’s one of our worst unsolved cases, so why have we forgotten Margaret and Seana Tapp?

IT should be one of Melbourne’s most infamous unsolved cases: a mum murdered and her little girl raped and strangled in her bed. So why have we forgotten the Tapp murders? Andrew Rule investigates.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE deviate who murdered Melbourne mother Margaret Tapp then raped and killed her little girl is probably reading this, hoping no one notices his fascination.

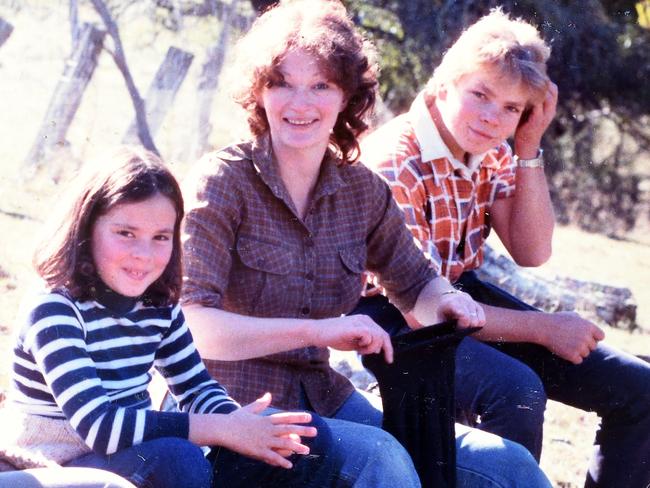

What he may not know is that he also claimed another victim: Margaret’s only son, Justin.

Justin Tapp wasn’t strangled like his mother and his little sister, Seana.

He was slowly poisoned by the horror of what happened to them.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST ITUNES | RSS

ANDREW RULE: BEANIE BANDIT THREATENED ME WITH A BRICK

COMANCHERO MC: INSIDE AUSTRALIA’S BADDEST BIKIE GANG

He rarely spoke about it but was haunted by the thought that if he’d been at home at the time, maybe it wouldn’t have happened.

He was only 14 then — just old enough to blame himself over the evil act that took two lives and destroyed his.

Calendars are cruel for the broken-hearted.

For Justin, the unbearable became too much when time moved closer to the 30th anniversary of the murders at Ferntree Gully in early August, 1984.

He had left Australia in 2001, but could not escape the demons that had already cost him a career and a marriage in Melbourne.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST ITUNES | RSS

In England, he was “Tappy” the chirpy, cricket-loving Aussie who was good at cooking and computers.

He soon met Wendy O’Donovan, the woman who would be his greatest support besides his mother’s older sister, Joan Nelson. But it wasn’t enough.

Behind the cheerful false front was a broken man who lost jobs and wore down relationships because he drank to blot out the nightmares.

STEPHEN MYALL: THE MAGISTRATE WHO CARED TOO MUCH

He ended up alone and unemployed in a tiny rented apartment north of London, a prisoner of his past and his crumbling psychological state.

Not that he was abandoned.

His Australian relatives stayed in touch as best they could.

His former partner Wendy and her two daughters remained friends and tried to stop him brooding alone in his flat.

It was Wendy who found him dead on June 3, 2014 when she went to check on him.

No one knows if he deliberately took his own life, or “accidentally” drank and drugged himself into oblivion.

The body had deteriorated so much the British coroner insisted on not only a toxicology report but formal identification by DNA testing.

This is ironic, because it is bungled or incomplete DNA tests that have covered the trail of the man who murdered Margaret and Seana Tapp.

Bad police work, bad forensics, bad luck

Justin’s death is the third act of a tragedy in a family let down by modern forensic science and old-time police work.

After more than three decades, the killer might expect to take his secret to the grave.

But how has he got away with it this long?

Is it luck — or did the investigation veer off course in the first days, the “golden hours” when most murders are solved?

That’s the question that torments the dwindling group of family and friends who wonder how a vile crime fell between the cracks.

And police aren’t the only ones who sometimes get it wrong.

Reporters do, too.

When the Tapps were killed in their house in Kelvin Drive, Ferntree Gully, on the night of August 7, 1984, this reporter was one of those working the crime beat at the old Russell Street police headquarters.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST ITUNES | RSS

We wondered why the double killing didn’t become one of Victoria’s biggest murder mysteries but, after a few brief stories, we let it fade away — unlike the Easey Street murders and the disappearance of Eloise Worledge or the Mr Cruel abductions.

And unlike the murder of Nanette Ellis in nearby Boronia the same year which preoccupied the same homicide crew — and the media — far more.

The Tapp double murder was as sinister as any of the others, but it never got traction.

That was because, at first, there was no new information.

Later, maybe, it was because of misinformation.

In most cases, police persuade victims’ relatives to make public appeals, hoping information from someone who’d seen or heard something suspicious might lead to a breakthrough.

Why didn’t that happen in the Tapp case?

One reason was that the family shunned publicity.

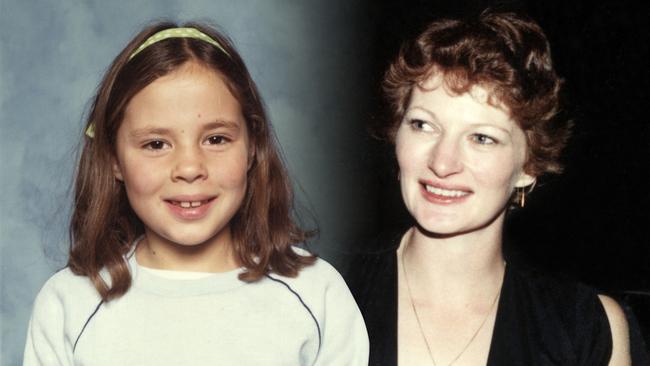

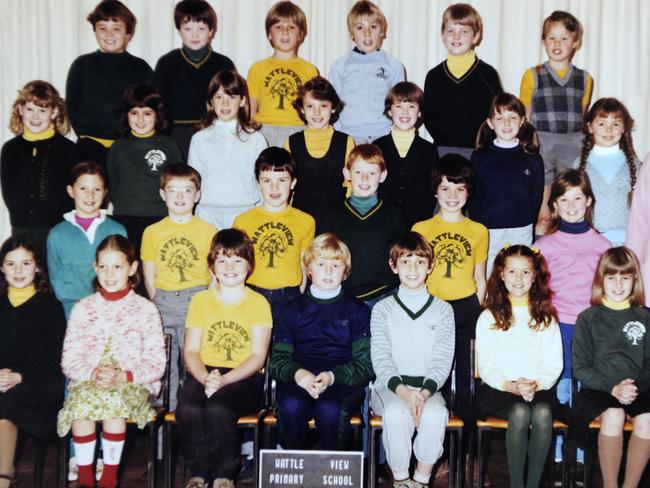

There was the confronting nature of the crime: Seana, 9, so young she had not graduated from the local Brownies to Girl Guides, had been sexually assaulted as well as killed.

Margaret’s ex-husband, Don Tapp, was a shy man who had remarried and had to shield his new family and Justin from the horror and the rumours.

Then there were Margaret’s parents, the Nelsons, longtime Ringwood residents.

They were religious and rigidly respectable, wary of any publicity reflecting on their 35-year-old daughter’s private life.

Alan Nelson was a member of the Masonic Lodge, as were many senior police of that era. He trusted police and probably had enough influence to smother potential embarrassments the investigation might reveal.

It was a time when Masons looked after each other — especially in the crime squads, where ambitious young detectives were known to join the Lodge, hoping to win faster promotion.

Margaret Tapp was a striking woman, with red hair and a generous smile.

She had left school young to take up nursing, but had gone back to the classroom to qualify to study law at Monash University. She planned to become a medico-legal specialist.

But if “Marg” was restless and ambitious, she was also popular, charismatic and easy to get on with.

Since her amicable marriage split with Don Tapp in 1979, she had gone out with several men, including medicos she worked with at the Angliss Hospital in Upper Ferntree Gully.

The most recent of these had bought the Kelvin Drive house and Margaret lived there rent-free until the doctor’s death in a car crash in early 1983, after which she agreed to buy out the house from his estate.

The killer didn’t enter by force

THE Tuesday evening of August 7 was just another quiet school night in Kelvin Drive. Number 13 was an unremarkable brick veneer, close to Burwood Highway.

After dark, most people were inside watching the Los Angeles Olympics on TV.

The killer entered the house without forcing anything, which suggests he was known there. Either he was let in the front door — or had let himself in the back door, which couldn’t be locked because the catch was broken.

Either scenario suggests someone familiar with the house; someone motivated by more sinister impulses than burglary.

Margaret’s car was in the drive, so it was obvious to an intruder that she was home. Slack police work did not reveal what Justin immediately did when he was allowed into the house after the murders — his mother’s jewellery was still under the mattress, untouched.

The time of the murders can probably be narrowed to the hour before midnight. A neighbour, Rosalind Bomford, heard a sound like a muffled scream just after 11pm.

Soon after, her dog growled. Across the street, Jack and Loreen McNamara heard the Tapps’ spaniel bark and howl around midnight.

They’d never heard the meek little dog so frantic.

Next day, Rosalind Bomford’s daughter Karen knocked on the door to see if Seana wanted to walk to school, but nothing stirred. In the afternoon, a friend of Margaret’s sister, Joan, dropped in.

He picked up the newspaper lying in the drive, knocked and left. He was puzzled because Margaret’s car was there but no one seemed to be home.

About 6pm, one of Margaret’s friends, a Scottish-born carpenter called Jim, came around as arranged to go to the opera with her. Jim was a former neighbour who had known her for years.

When no one answered, Jim went to the faulty back door and went in.

He found Margaret tucked in bed, a law book next to her.

The whole scene looked almost normal — except that she was dead. What he didn’t see under the covers were marks on her throat and injuries to one side of her head.

Jim said later he hoped then it was suicide and that Seana would be all right.

He rushed into the Bomfords’ house next door, praying the child had stayed the night with them.

After calling the police he returned to the house and found Seana’s body in bed.

The local police arrived, then veteran homicide sergeant and his young offsider, who were diverted to the scene by D-24 on their way home.

The crew would also include a well-liked but doomed detective, John Hill.

The unfortunate Hill would later commit suicide after being accused of twisting evidence to protect fellow detectives who shot dead an armed robber, Graeme Jensen, the killing that sparked the Walsh Street murders of two young policemen.

Hill was cleared of any offence but his state of mind underlined the predicament of police who felt unspoken pressure to protect fellow officers.

She looked like she was asleep

WHEN the homicide detective walked into the house, the scene hit him hard.

Years in the job had got him used to ghastly sights, hiding anger and disgust with a blank look and black humour.

But the little girl lying still in bed with the covers pulled up looked as if she were asleep and that shook him.

He had a daughter the same age.

He cried that night, he would tell me 20 years later, staring into his drink.

At first, it looked like “a domestic”, as most homicides are: arguments between couples or in families that flare into murderous anger.

The killer was nearly always someone close to home.

At first, Jim the quiet widower seemed the obvious suspect. In the time it took for detectives to be satisfied it clearly was not him, the trail had cooled and split in a dozen directions.

The pool of potential suspects was growing, but none seemed to stand out.

Except to Margaret’s sister Joan, that is, who told the detectives Margaret had confided in her about an ex-policeman who had annoyed her with unwanted attention.

DNA testing was still almost science fiction in 1984.

Fingerprints, hair samples and blood-typing were the main forensic tools.

There were plenty of fingerprints in the house but they were eliminated because they belonged to friends, neighbours and relatives with a legitimate reason to visit.

This fact, of course, could mask someone who knew the victims well enough to have visited — or who had a reason to enter the crime scene afterwards.

Footprints, hairs and other clues

They found two types of hairs on Seana’s clothing and bedding: a long blond one and shorter ones, grey at one end and dyed brown at the other, as if from a vain older person.

The hairs, of course, could have come from anyone, any time, and for innocent reasons: by themselves they could suggest a suspect but not convict a killer.

There were other clues.

Fibres found on the victims’ necks implied they had been strangled with rope.

There were semen stains on Seana’s nightdress, which supposedly did not reveal a blood type but would eventually produce a weak DNA sample.

And there were unidentified footprints in Margaret Tapp’s bedroom and the bathroom.

The prints were from Dunlop Volley sand shoes, with their distinctive ripple-edged sole.

They didn’t belong to Margaret or Seana or anyone else police could place at the scene.

At the time, investigators reckoned Volleys were so common there was probably a pair in every house.

As it would turn out, DNA tests are all too fallible.

But one thing a suspect can’t alter is the size of his feet.

Of course, that fact would only help if someone had measured and recorded the footprints precisely.

If that was overlooked, it’s one more hole in a case littered with them.

A little rule bending under the “Old Mates Act”

WHILE the police were distracted by trying to shake Jim’s alibi, the principle of “preserving the crime scene” wasn’t followed as rigorously as it should.

That might explain why the former policeman that Joan Nelson had named was reputedly allowed into the murder scene.

The man was also friendly with at least one well-known senior homicide squad figure (not involved in the case) and so presumed to be above suspicion.

Joan Nelson and her brother Lindsay heard later, through a friendly police source, that his pretext for entering the scene was vague — something about retrieving books or letters or other property he had sent or lent Margaret.

Presumably he told police at the scene he wanted to prevent any embarrassment or time-wasting when an inquest was held.

A little rule bending under the “Old Mates Act” must have seemed harmless but had implications that would later become clear: the visitor’s fingerprints (or even hair samples) would have to be ruled out because he’d been at the house after the murders.

Joan recalls that the former policeman refused to give his prints, as was then every Victorian’s legal right.

Meanwhile, the only appeal detectives made was for the driver of a red Ford utility with distinctive “12-slot mag wheels”.

If the detectives had questioned Margaret’s brother Lindsay closely, instead of not at all, he would have told them what he told this reporter many years later: a man he worked with in 1984 had a red ute with mags, and had once helped deliver a table to Margaret in Kelvin Drive.

There were other leads — too many. Just down the street was a family most locals avoided. The youngest of several sons living at home was a teenager known to make suggestive comments to older women in the street.

The kindly Margaret had let him mow her lawn and wash her car despite neighbours’ warnings.

The youth’s older brothers were never eliminated, to their puzzlement.

Neither was their sister’s boyfriend, reputedly later jailed for sex offences.

Blunders and false leads

THEN there were the men Margaret Tapp had met in the previous few years. One medical man would supposedly be tested and cleared by DNA but if the rest were spoken to at all, their alibis were accepted.

part from several doctors, there was a law student, a driving instructor and a young man Margaret had met at a disco.

Any one of them might have been the killer or could have known someone who was.

Perhaps investigators were distracted again from casting the net wide — this time by the tempting theory Margaret’s most recent and most serious affair with a doctor could have upset the man’s family so much it created a motive for murder.

The fact that the doctor had paid for the Kelvin Drive house — before dying in a car accident the year before the murders — added spice to a far-fetched circumstantial case.

RAPE VICTIM’S COURAGE TO RISE ABOVE EVIL

In the absence of any more solid leads, Margaret Tapp’s relatives were led to believe the “revenge” scenario for 20 years, despite the problem that the theory didn’t quite fit the facts.

The most obvious fact was that the murders were not just sexually motivated but deviant.

The strangler had sexually assaulted a young girl.

In other words, he was an unarmed paedophile apparently acting on impulse. Hardly the profile of a hired killer.

There were a few major blunders that emerged over the years.

One was when it was wrongly concluded (then leaked) that a series of loans made by the doctor (and, later, his wife) to a friend of theirs well before the murders could have been some kind of “payment” to a “hired hitman” by the supposedly homicidal widow.

Bank records show four loans totalling $52,000 — and that the borrower repaid them with $18,000 interest.

So if the doctor’s friend was paid, by cheque, more than a year in advance to do the murders, he would be the first paid killer in criminal history to repay his “fee” after performing the task.

The wrong man — and a major stones left unturned

Just as careless, but more humiliating for the police, was when an enthusiastic detective — apparently happy to abandon the paid “hitman” theory — in 2008 charged a bewildered prisoner called Russell John Gesah with the murders.

When Gesah’s 1984 alibi proved embarrassingly unshakeable, Detective Senior Sergeant Ron Iddles insisted that the forensic section must have bungled the tests, compromising the key DNA sample. He was right.

The Gesah debacle led to a lawsuit and a new rule not to charge suspects on DNA evidence alone.

As the new head of the police union and no longer in the homicide squad, Iddles can speak bluntly.

He says the Tapp file has dozens of untested leads demanding painstaking detective work.

Perhaps the first thing to do is to fix past mistakes instead of ducking them.

More than ten years ago a thin-lipped homicide officer angrily insisted every key suspect in the case had been cleared by DNA.

Which is strange, because a (since retired) detective who did most of those swabs now says he did not interview the ex-policeman who had visited the Tapps’ house — and did not hear of anyone else testing him, either.

After more than 30 years, a murdered mother and her two dead children deserve better.

One of the last things Justin Tapp told Wendy was he always believed the killer was “someone higher up”. Someone with influence.

Whoever goes to see potential suspects might check their shoe size ... and whether any of them ever had a link with the Girl Guides or Brownies.

It could paint a whole new picture.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST ITUNES | RSS

MORE ANDREW RULE: