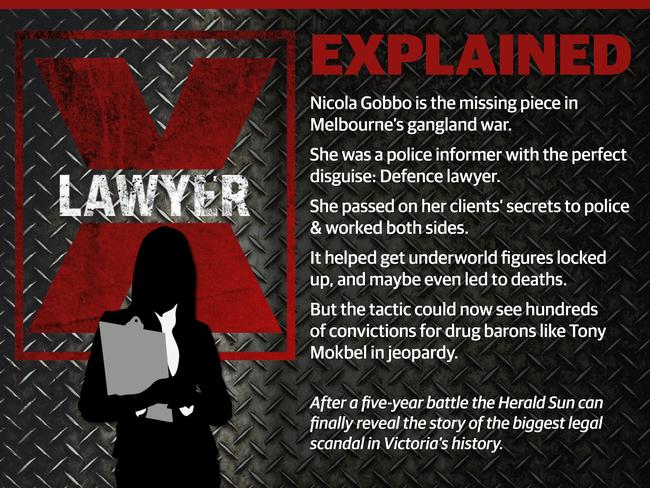

PART 1: Nicola Gobbo couldn’t be in court today, the judge was told. She was delighted, radiant and a bit tired, the story went, after giving birth to a girl. The County Court hears excuses every day. For once, here was a no-show that everyone could celebrate.

Yet there was more to the tale. There always was with Gobbo.

The fairytale scripting was true enough — high-flying lawyer meets motherhood — as far as it went.

She did give birth in 2013, and consequently could not represent her client at a mention hearing for his forthcoming trial on drugs charges.

He would go on to be sent to prison.

And that’s where the script took a strange turn, according to some close to her.

PART 3: THE MAN IN THE GOLDEN COFFIN

GET THE LIFE & CRIMES PODCAST ON iTunes, WEB OR SPOTIFY

Normally, the lawyer-client relationship dims in the wake of courtroom machinations.

Instead, Gobbo began visiting this client in jail in the “family area” in Port Phillip Prison, with her baby girl. The defendant in court that day, or so the story goes, was the father of her daughter.

The prosecution didn’t know. Nor did the judge.

A lawyer witnessed the prison catch-ups three or four times.

“Say goodbye to Daddy,” Gobbo would invite her daughter to say to the prisoner and client.

Yet the rumoured twist did not shock those best acquainted with her. Its telling will however bring comfort to the once high-ranking Victoria police officer whose career was often plagued by rumours that he was the baby’s father.

This was just another secret in a career built on them.

Another blurry line trampled in a vortex of ethical shadows, where Gobbo bounced between cops and crooks.

For Gobbo was routinely informing on her clients, some of whom happened to be the most menacing figures in the gangland wars of Melbourne.

They told her things because they trusted their lawyer. She then told the police. Years later, she sold out Victoria Police, too.

Gobbo manipulated justice in Victoria by sharing her confidences.

Victoria Police command empowered her in an arrangement hidden from both the crooks and the judges.

The lawyer was no fearless representative of her clients: she was a gangland player who straddled ethical divides and diverted the course of the war.

She furnished police with thousands of details on the most notorious gangland identities, their drug cooks and the mafia.

Sometimes those secrets escaped her, such as the time in 2004 or 2005 when Carl Williams figured out that Gobbo was a “dog”.

Williams was years ahead of most.

Her desire to be involved — to shape events or, as some put it, to meddle — trace back to her schooling.

Gobbo, the teenager, was curious about politics.

As a Catholic schoolgirl from the leafy east, Gobbo lamented the overthrow of John Cain as Victoria’s premier in a letter to the Herald Sun.

Life darkened with the death of her father when she was in her teens, and she began frequenting nightclubs.

She took over the teaching of legal studies during year 12: she seemed more across the curriculum than the teacher.

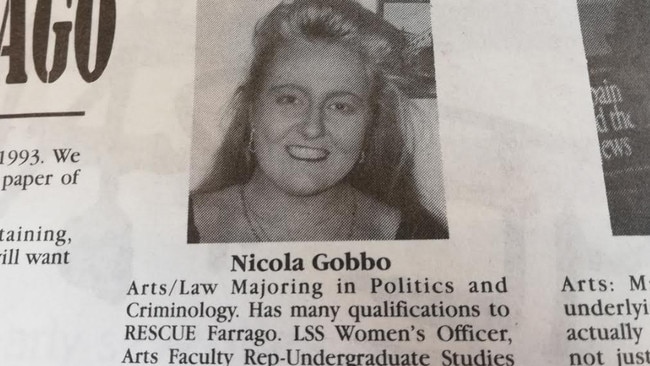

She wanted to be prime minister. She would herself delve into the dark arts a few years later at Melbourne University, where loose student politics tactics were fair play.

She helped run the university’s student newspaper, Farrago, because extra-curricular activities stopped her becoming boring and insular, she explained. She was quick at seeing through the haze to the essence.

Thrusting herself forward would become a signature move. She always seemed to appear at moments that mattered.

There she was at the Tunnel Nightclub on October 7, 1991 — the night Collingwood footballer Darren Millane died while driving home with a blood-alcohol content of .32. Millane was usually “the life of any party”, Gobbo later told the coroner, except this night he didn’t seem to know where he was or what he was doing.

The lawyer’s Carlton housemates were convicted of serious drug offences in 1993.

A few years later, she wrote a statutory declaration that doubled as a national headline. In it, Gobbo noted her support for the ALP and spoke of fabricating a campaign leaflet for student elections.

She was concerned at the time: the stat dec exploded as a 1996 federal election issue only days after she graduated from her law degree.

She muddled through this controversy: two years later the 27-year-old was admitted to the Victorian bar.

She was one of the youngest ever women barristers.

Soon enough, she was defending miscreants whose freakiness attracted courtroom journalists. The Czech bird breeder smuggling parrot eggs in his underpants. The pervert who put a camera in the female toilets. There were other clients, too, such as Bandali Debs, who killed police officers.

Through him she first met Paul Dale, a cop later accused of murder.

In Gobbo and Dale bloomed a union that crossed lines.

Their relationship offers the merest snapshot into Gobbo’s world of intrigue.

They would be confidantes and drinking buddies, allies and enemies.

Dale was the main suspect in the killing of her client, Terry Hodson, with whom Dale had been accused of committing a burglary.

Dale said he and Gobbo were lovers. She arranged meetings between Dale and gangland head Carl Williams — who later said he arranged Hodson’s hit at Dale’s request.

Dale was well aware that she stood apart in courtrooms dominated by men in dark suits. Gobbo was easy to talk to, confident.

She was the best lawyer, in part because she was a good study of human nature.

“I think she loved the limelight that came with dealing with both the major criminals and detectives who caught them,” Dale observed.

There were mafia bosses and speed cooks.

Then there was Tony Mokbel.

He was stranded in prison in 2001 when Gobbo turned up.

Let me represent you, she told him, beginning a relationship that — as he tells it — featured a little-known moment, years later, when she flagged imminent murder charges against him, prompting “Fat Tony” to go away for a while.

His holiday became known as Australia’s biggest international manhunt, with Mokbel having escaped on a luxury yacht and hiding out in Greece.

Call it serendipity or dumb luck. Gobbo’s career ascent coincided with a Templestowe execution of a man in his underpants.

Alphonse Gangitano was a thug: he also boasted gentlemanly pretensions and had a penchant for literature. His 1998 death was a fitting start to a gangland spree of caricatured notoriety.

A city would be captivated, a police force confounded; to this day, most of the gangland deaths — almost three dozen deep — remain officially unsolved.

How was this happening? The dead could not speak; the living would not.

But old-world notions of loyalty among crims were obsolete.

A body count, fuelled by greed for power and paranoia, mounted.

The public glimpsed an underworld of suburban pill presses and hot heads, where hit men roamed and their masters brooded. Making sense of the bloodshed, knitting the deaths into a cohesive thread, became a kind of local sport.

PART 8: HOW WE UNCOVERED THE TRUTH

Gangland was brutal and, for many average Melburnians, faintly comical.

Villains got mistaken for pseudo celebrities. When a police officer asked Williams, in desperation, to stop leaving bodies in the street, the story goes that Williams asked whether he would prefer them in wheelie bins.

The next gangland victim, Mark Mallia, was found in a wheelie bin.

The biggest question was: where would it end? It would take a dozen years and, in the end, the inglorious sellouts of the criminals themselves when, one by one, scumbags clambered to inform on scumbags.

Most gangland convictions would hang on the testimony of criminals informing on criminals. In courtrooms, rapists and murderers would be reinvented as purveyors of truth. Even their flimsy words could get convictions.

Yet the police — and prosecution — had another tool.

A most unlikely source of power that bypassed the tangle and inconvenience of ethics and fair play.

Gobbo had moved fast, and well, into chambers with the best criminal barristers in Melbourne.

Con (Heliotis QC) would often serve as counsel for her clients at trial. She would greet Robert (Richter QC) and Phil (Dunn QC) daily. Her prescribed role, as with all defence lawyers, was simple enough. She sought neither truth nor justice, but the best outcomes for her clients. This was her ethical imperative.

Through Mokbel she had met Williams, who also farmed clients to her.

Interestingly, Williams’ ex-wife Roberta has claimed that Gobbo told him to “f**k off” overseas instead of facing criminal prosecution for murder.

Williams would instead heed the advice of Roberta, and get killed in jail in a horror bashing with a bike stem.

By then, Gobbo was known to the public.

She was the gangland lawyer photographed on the court steps. She made headlines herself at times.

Her silver BMW erupted in a fireball outside a South Melbourne hotel in 2008. In dousing the suspicious blaze, firefighters plucked two bags of cash from the boot.

Within the gangland circles, as Roberta Williams once put it, everyone knew that Gobbo “got information from the police, the lawyers, the judges, whoever, and that her information was always right”.

One day, after assisting Mokbel in a bail application, she received a kiss before the pair left court in a black sedan.

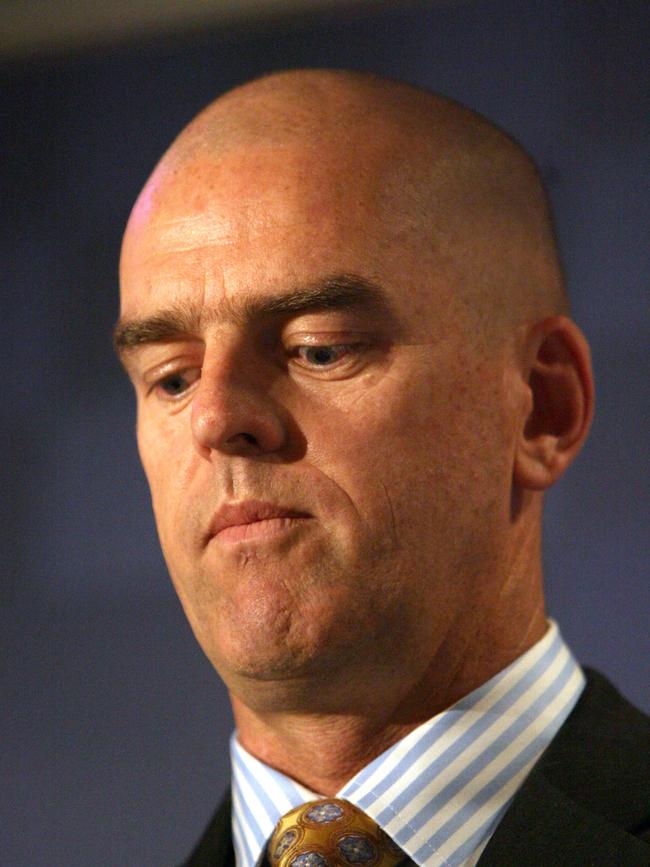

What the gangland figures didn’t know was she was also colluding with Simon Overland, the ambitious head of the taskforce seeking to halt the war, who went on be Victoria’s chief commissioner.

For a time, Gobbo and Overland would dine together at an eastern suburbs golf club, presumably to exchange secret tidbits. In a culture of nicknames, they were The Enforcer and The Secret Weapon, when he, like a succession of police handlers, referred to her as 3838.

When Gobbo represented Williams and his lieutenants, or Mokbel and his cooks, she would convince the more junior members to turn on their seniors, on the orders of her police handlers.

Hers was uncharted territory, a sump of half-truths and hidden agendas.

There were few explanations and no safety nets.

She offered legal advice that her clients, years later, now argue was intended to entrap them.

Their affidavits, prepared as part of until-now secret bids to overturn their convictions, affect an offended tone, the irony being that such hardened bastards sound genuinely upset by the moral flimsiness perpetrated upon them by someone they trusted.

For Gobbo was puppet and puppeteer.

Vixen and illusionist. A siren in the misogynists’ jungle.

Gobbo presents herself in her statements as sympathetic and misunderstood.

But her evidence is marked for its lack of explanation.

How could she represent one person while assisting another with opposing interests?

Yet lawyer X has gone largely overlooked in investigations that otherwise hunted down the smallest of participants. She is a corner piece in the gangland jigsaw.

At times she loomed as a person of interest in police investigations. But she has always faded from the crosshairs of focus. She was a protected species, another kind of freak in the zoo of barbarity.

For a long time, it was like the CIA and Jason Bourne. It ended the same way, too, when she turned on Victoria Police and sued the force — an unholy menace turning against its maker.

Her unexplained information gaps did prompt the concerns of some legal colleagues at the time, as well as her clients. She set off the antennae of female peers.

Her informing may have begun soon after those first days when she was pictured celebrating her bar entry. Eight years later, about the time she was officially registered as police informer, Williams wrote of the lawyer’s deceit.

She was playing the most dangerous of games.

Bad things happened to police informers — one, in 2002, recorded his own shooting, in the head and stomach, on a concealed tape recorder.

Another, Terry Hodson, was killed while watching TV in his trakky daks, along with his wife, Christine.

WHAT WAS THE GANGLAND WAR ALL ABOUT?

Williams killed four foes, if not many more.

The hit on Jason Moran — in front of Moran’s kids — at an Auskick game in Essendon happened in a busy public place on a Saturday morning.

Williams had invited Gobbo to his daughter’s christening, and he expressed hurt that she had betrayed him.

“There is a lot more stuff that I cannot say at the moment, but believe me I am 100 per cent right, as much as I don’t want to think I was,” he wrote about her to a friend in a letter from prison.

He would be one of the last insects to die in a gangland web that threads back to his being shot by Jason Moran in a park in the late 1990s.

Gobbo had figured near the start of Williams’ notorious rise — and she would help police investigate his death.

Most of the criminals are buried or behind bars now, their stories the bullet points for a celebrated TV series. The gangland wars are a historical novelty, a badge of difference for a city that boasts what economists call liveability.

Many of the police officers are in disgrace. Or have moved on.

Among them was Sir Ken Jones, Victoria’s once deputy chief commissioner.

It’s believed he was concerned about misconduct issues, and the serious and systematic abuse of Victoria’s criminal court process. He feared villain acquittals — dozens of them — if Gobbo’s role was properly revealed.

Sir Ken fretted about breaking the law to win the war.

Now, after closed-court arguments spanning more than four years and going all the way to the High Court, the Herald Sun can expose the Gobbo conundrum.

She starred in a Victoria Police decision to bend the law to solve the war.

ESKY MURDER CARL GOT AWAY WITH

Few observers grasped her reach.

She shaped events almost as much as the headline villains. She was no one’s friend and everyone’s problem. She was the enigma and the player.

She has claimed stress and depression at various times and it’s little surprise, given the untold risks of her chosen role.

But only recently she was being recognised for her volunteer work.

She has endured the harshest of environments. She has burrowed in retreat and pounced in attack.

That bite has put people behind bars and ended careers.

Her motives have eluded the understanding of the closest observers, though self-preservation is critical to any understanding. It’s as good a guess as any.

“She wanted to be wanted,” says Zarah Garde-Wilson, a fellow gangland lawyer, in explaining why someone secretly shaped investigations, trials and changed the course of justice in Victoria.

Gobbo is certainly an unusual species, a November child, who has adapted to the changing environment.

Always there and always two moves ahead. She’s been known as both informer 3838 and The Secret Weapon.

But perhaps The Scorpion fits best.

MORE CRIME:

DEATH STARE: CARL’S EVIL KILLER

‘I miss being able to talk to them’: Tribute for slain Aussie brothers

A tribute has been unveiled where Australian brothers Jake and Callum Robinson and their American friend were murdered during a surf trip.

Melb private schoolboy’s stunning Russian mafia admission

An investigation into former Melbourne private schoolboy Damien Carew has taken a dramatic turn after his latest police confession.