In law and order circles, here was the rumour of the 2013 Christmas party circuit: A former police officer on the rise had apparently been sleeping with a barrister for the biggest criminals in Melbourne’s gangland war.

There might even be a love child, it was whispered.

Herald Sun crime reporter Anthony Dowsley sensed an opportunity to probe further.

The truth or otherwise of the “fling” almost mattered less than the existence of the rumour.

The former officer was still young, ambitious and harboured hopes for the highest job before he left the force in a hurry.

PODCAST: LIFE & CRIMES ON iTunes, WEB OR SPOTIFY

The talk might have cruelled his career.

He and the police hierarchy were keen to dismiss it.

Dowsley started asking around. No one wanted to say much.

Dowsley was not particularly interested in the purported affair with the barrister Nicola Gobbo.

There was something else about Gobbo that niggled.

His first significant break was little more than a nudge and a wink.

Dowsley was chatting with a source about Gobbo’s perceived omnipresence.

She was always hovering; on the periphery, or plonked in the middle of things, where she often had to be extracted.

She seemed, well, protected. Was she too close to police?

He voiced a sudden impulse. Was she a police informer?

The source stared. And gave Dowsley a thumbs up.

Dowsley had also noticed that Gobbo had unusually pitched client against client in some cases.

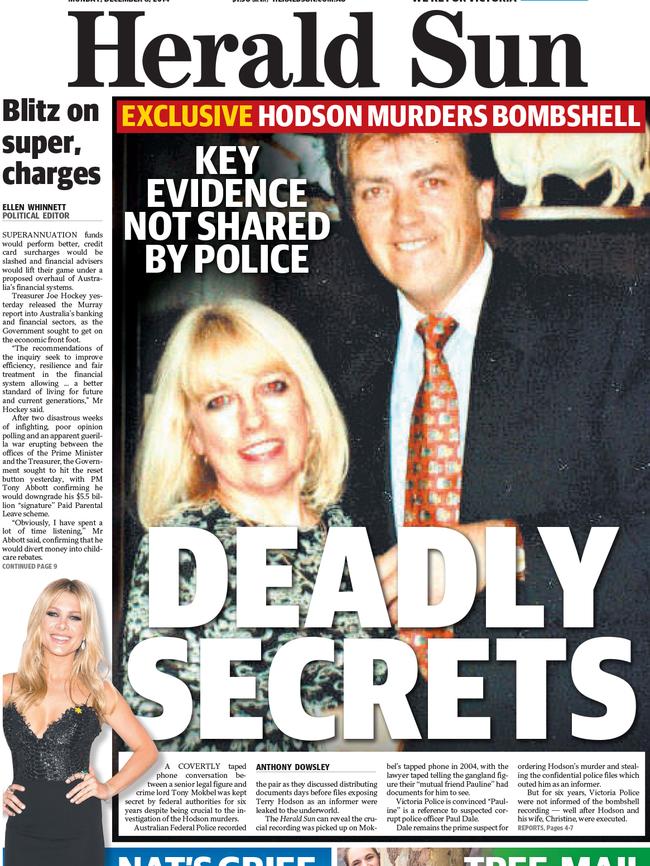

There was her involvement as a witness in the collapsed prosecution of former detective Paul Dale over the murder of Terence Hodson.

And the late withdrawal, by police, of her as a key witness in another Dale trial, leading to about half of the charges being dropped.

DEATH STARE: CARL’S EVIL KILLER

This was more than unusual. It was odd.

A second source met Dowsley in a city coffee shop. The chat started on the affair.

It was hurtful and it was nonsense, probably provoked by the officer’s foes in the force, Dowsley was told.

The officer in question had had no contact with Gobbo, who had recently given birth, for years, the source explained.

Their interaction had been “a long time ago — when she first started informing for police”.

Pardon?

Dowsley was hunched at a wooden table, his faded black canvas bag at his feet, taking no notes, as usual, lest the subject take fright and clam up.

He was trying to look calm.

Was this the confirmation he sought, evidence for a slender thread of innuendo that had dangled, just out of reach, in police and legal chatter for months?

The hints had lain scattered here and there.

Dowsley had been collecting them, like jigsaw pieces.

He asked the source another question. How had the officer’s secret police relationship with a defence lawyer started?

Gobbo’s motivations were neither betrayal nor greed, the source said.

She went to police, eager to help. She had confided that she couldn’t look in the mirror when she defended such “scumbags”.

WHAT WAS THE GANGLAND WAR ALL ABOUT?

Here was the making of a major corruption scandal.

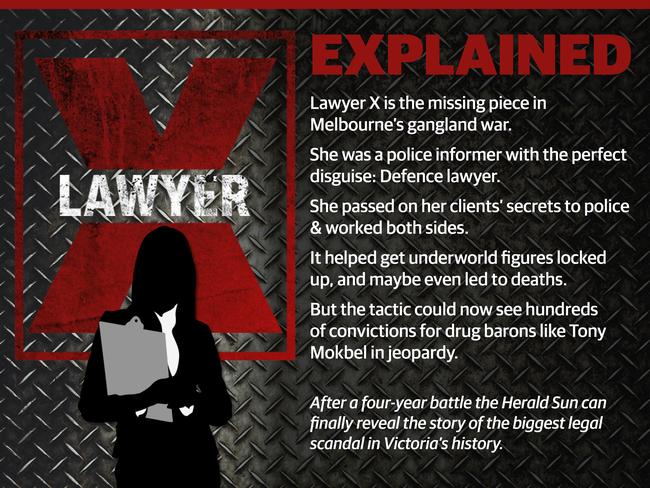

A prominent lawyer recruited by police to inform on her criminal clients.

Such an arrangement was almost unheard of. If such well-placed sources of information ever existed in the fight against the New York mafia or the Chicago mob, they’d never been outed.

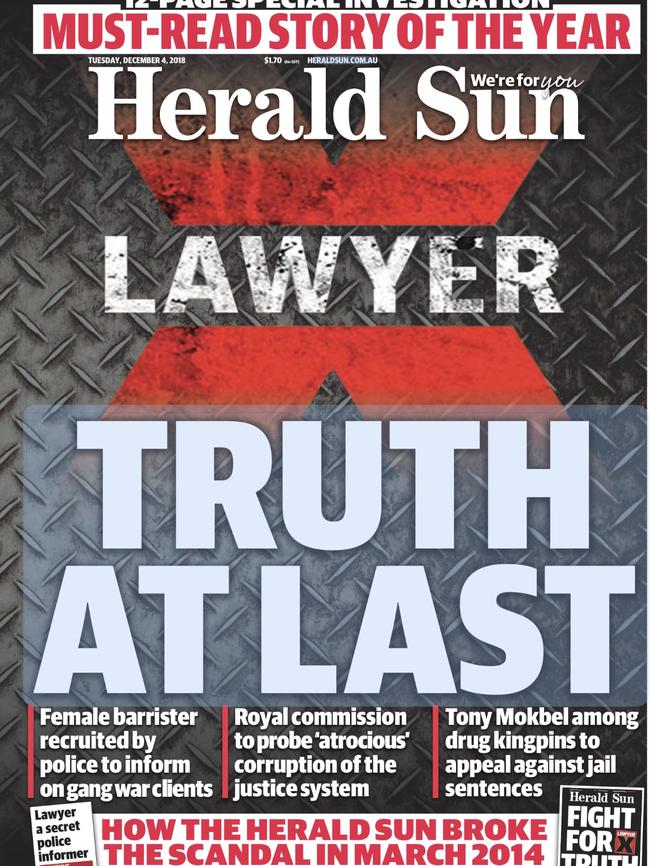

Dowsley’s bombshell Herald Sun story, headlined “Lawyer a secret police informer”, went to press on the night of March 30, 2014, on page one of the next day’s paper.

Herald Sun lawyers had approved that the crux of what Dowsley had learned could run in the newspaper’s first edition.

At the pub that night, he was debriefing about the scoop with a beer when a call came through.

In a throwback to another era, the police were trying to stop the presses before the story could be published in the paper’s second edition — the one that reaches most readers.

In a hastily-convened Sunday night session, lawyers buzzed like flies on dung; they would feed off this for years.

Lives were at risk, lawyers for the police argued, notwithstanding that so, too, was Victoria Police’s dirtiest little secret in decades.

The tale of Lawyer X was out, if only just.

The Herald Sun couldn’t tell you then who it was, exactly what she had done, why she had done it, or how the justice system had been corrupted by Victoria Police using her.

ESKY MURDER CARL GOT AWAY WITH

But those who knew a bit, knew enough.

Take Mick Gatto. Gobbo had been Gatto’s lawyer for a long time; the pair had been seen to fraternise at Wheat restaurant in Lonsdale St.

Years before, Gobbo had warned Dowsley not to describe her client as a “gangland” player, compelling Gatto himself to calm her.

Gatto now sat Dowsley down to a pumpkin ravioli in his Lygon St restaurant, to ask questions about Gobbo and a hitman associate whom Gobbo had represented.

Gatto had spoken to Gobbo since the Herald Sun story. She had denied to him that she was a police informer.

(Last week, in the rush of new facts that superseded old suppositions, her claim to Gatto then was scuppered by another claim - made by Gobbo herself. Buried in the release of Supreme Court documents, she listed Gatto and his Carlton crew as subjects of some of her most significant informing.)

At the same time she was denying it, police were privately confirming that Gobbo was registered as an informer from 2005 to 2009.

Dowsley is a good listener, imbued with chameleon charms marked by sartorial indifference. He soaked up gossip that conflated notions of sex and impropriety.

Rumours abounded about a former officer who had recently left Victoria Police with a hush unexpected for someone of his rank.

He had sat on gangland taskforce steering committees in roles that had fanned nasty gossip.

Why hadn’t he declared the Gobbo relationship (naturally, rumours become truths once they were repeated a few times), given her intimate involvement in the taskforce investigations? Her new baby seemed fatherless. Was it his?

That question - or rather, the ethical minefields that it threw up - prompted Dowsley to chat with Rob Stary, the high-profile lawyer.

Police rumours often seeped to Stary’s office, but Stary alighted on something else — the recent Australian Crime Commission case against a former detective, Paul Dale.

Gobbo was supposed to be a star witness in that case, yet she had been excused on safety grounds after a purported death threat.

“This is weird,” Stary said. “Something’s going on here.” His reasoning was simple.

Justice is blind and inexorable. Courts very rarely bend to excuse a witness who receives an anonymous threat.

HITMAN TAKES HODSON SECRETS TO GRAVE

By now, Dowsley had quietly spoken to one or two investigators who knew Gobbo well.

If keen observers were not across the breadth of her informer status, they were aware of her constant presence around police stations.

It was odd to see a defence barrister with her familiarity, buzzing around police.

Dowsley visited Zarah Garde-Wilson, the gangland lawyer, to ask about a man beating a woman.

The conversation turned to Gobbo, Garde-Wilson’s old colleague and foe.

Garde-Wilson had warned clients that something appeared strange after Gobbo gained undue access to clients in police stations.

The same clients appeared to give full statements to police that did not serve their best interests.

In one case, a teenage boy was arrested inside a drug house. Garde-Wilson got the call in the middle of the night and duly waited at St Kilda Rd police complex to talk to her client. Gobbo appeared, was ushered straight in, and texted Garde-Wilson: “All sorted. You can go home.”

Garde-Wilson didn’t go home. The boy, who was visibly shaking, told her that Gobbo advised him to tell police everything he knew to improve his chances of bail.

It was the worst legal advice, Garde-Wilson says, that implicated him in crimes for which there was otherwise no evidence and stood to expose him to reprisals.

He would have gotten bail whether he spoke to police or not, given “they had nothing on him”, she says.

Gobbo also approved a joint legal conference between shared clients, Garde-Wilson claimed, then explained to Justice Betty King in court that Garde-Wilson had erred in arranging the conference.

Her treachery led to Garde-Wilson being barred from representing Carl Williams, she said.

Garde-Wilson, known as feisty and outspoken at the time, said she was “a thorn in the side of police” because she expressed her concerns about Gobbo’s strange behaviour.

After this, Dowsley wielded theories and ideas.

Gobbo had raised suspicions, yet Dowsley had few hard facts.

He itched for concrete details, given the notion of a defence lawyer doubling as a police informer appeared so unlikely.

He heard whispers about the divisions Gobbo’s role had opened within police command. Some brass feared that her safety was being unreasonably jeopardised.

They included former deputy chief commissioner Sir Ken Jones.

They were particularly concerned after she was deregistered as an informer and turned into a witness in a murder case against Dale, the former detective.

She had worn a wire to secretly record Dale discussing Carl Williams’ claims that Dale had hired him to kill a police snitch, Terry Hodson, in 2004.

Her decision to co-operate with police shocked all, and had required all of Gobbo’s fabled quickness — and poise — when clients asked about the Dale wire recording.

She fielded queries from Tony Mokbel. And Rob Karam, a big-time gambler and one of Australia’s biggest illicit drug importers.

He was “suspicious”, he says in court documents, until she explained how she was a “victim of circumstances”.

The “police had used listening devices on her without her knowledge”, she said.

Karam believed her, and unwittingly kept a police informer as his legal counsel for the next four years.

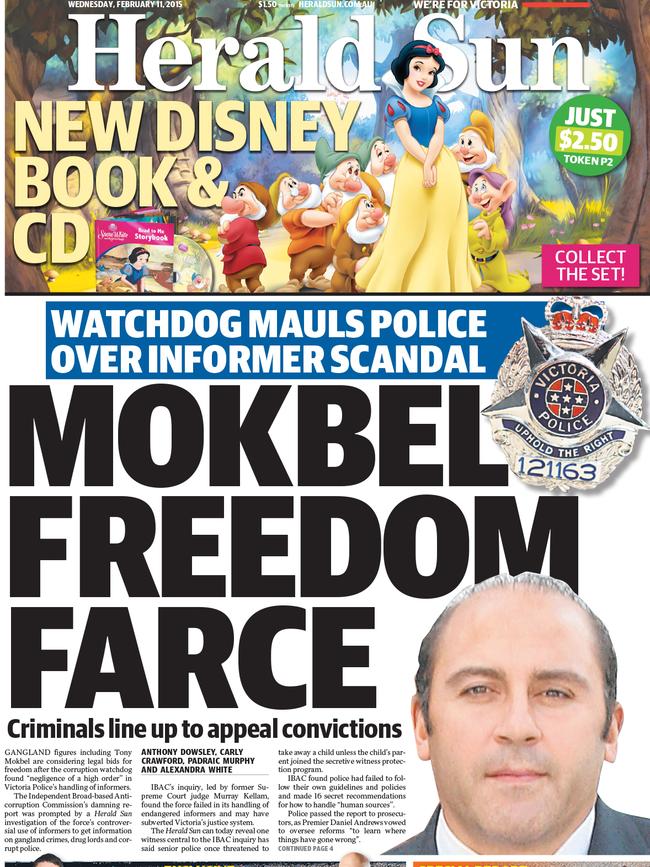

Karam’s case would be named in the Kellam Report, a probe into the police’s use of informers prompted by the Herald Sun’s reporting.

By then, 12 months had passed since the initial Lawyer X story.

The Herald Sun was describing the saga as a “scandal” and arguing for a full judicial review.

Justice Murray Kellam did not publicly blame media reporting for the poor handling of informers. Nor did other inquiries into the perceived failings of checks and balances of the Victoria Police informer system, including probes by the state ombudsman and former police chief commissioner Neil Comrie.

A police officer invited Dowsley to coffee in Richmond to discuss Gobbo.

He didn’t make a lot of sense, except to leave Dowsley wondering if the officer was clumsily trying to extract information from him. Documents released last week revealed the officer’s identity as one of Gobbo’s six police handlers.

A wise head, close to cops and crims, took Dowsley aside, to explain that desperate times sometimes require desperate police measures. Police journalists need good police sources, the wise head warned Dowsley.

About a month after the initial story broke, in a cordial meeting over white wines, Dowsley questioned Gobbo again over whether she had been a police informer.

She again denied it.

As time went on, however, Gobbo felt that her identity as a police informer had been revealed to all who had been stung by her subterfuge.

“When I say ‘the whole world,’ I probably should clarify that to anyone who would have a reason to harm me, because the people – a lot of people in prison, the Herald Sun is their Bible,” she would tell the Supreme Court.

“It’s known as the Bible in there. There was a – initially, when the first article came out and it said ‘Lawyer X’ there was a bit of speculation about who it was.

“But as more articles came out, anyone who would want to do me harm or was sitting in prison would read the stories about Lawyer X and know it was me.”

By then, Dowsley knew police had 5500 information reports based on her informing, and had recorded 128 contact visits with her.

That information had been suppressed by a court after the Herald Sun posed questions to police about it.

Dowsley and the Herald Sun knew far more than could be revealed. Until now.

THE LAWYER X STORY SO FAR:

PART 2: THE BETRAYAL OF THE HODSONS

PART 3: THE MAN IN THE GOLDEN COFFIN

PART 7: BALI AND THE BIG REVEAL

MORE CRIME: