VP Day 75th anniversary: How US troops changed Australia forever during World War II

From hot dogs to dances and social etiquette, the thousands of US troops stationed in Ballarat and across Australia during World War II had a profound impact on the way we live today.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

About 250,000 American service personnel were stationed in Australia during World War II, and their presence had a profound effect.

Tens of thousands of US troops arrived in Melbourne in early 1942, energising a city that was subdued by men and women serving overseas, rationing and the threat of a Japanese invasion.

The Americans helped revolutionise retail, with cafes catering for unheard of foodstuffs such as hot dogs and hamburgers, taught us the latest dances and captivated us with unflinching politeness.

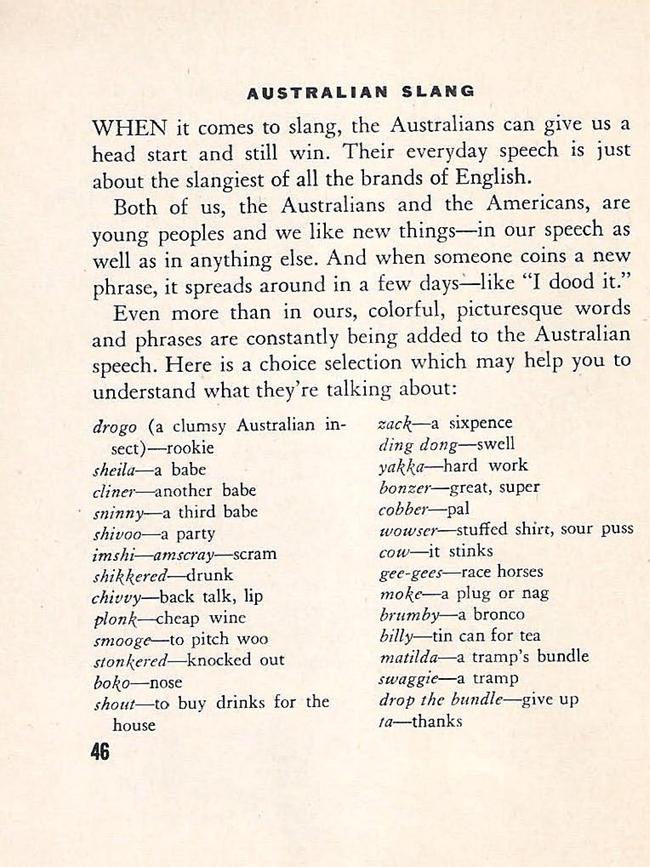

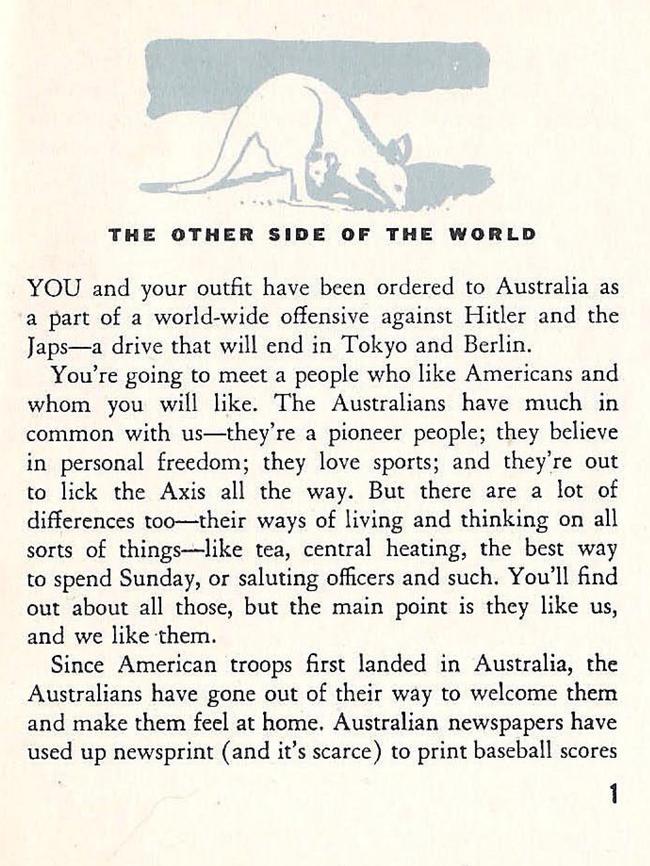

To head off cross-cultural misunderstandings, they were issued with a Pocket Guide to Australia, a thumbnail sketch of Australian history, geography, currency, our soldiers’ characteristics and our customs. It also included the words to Waltzing Matilda and an Australian slang glossary.

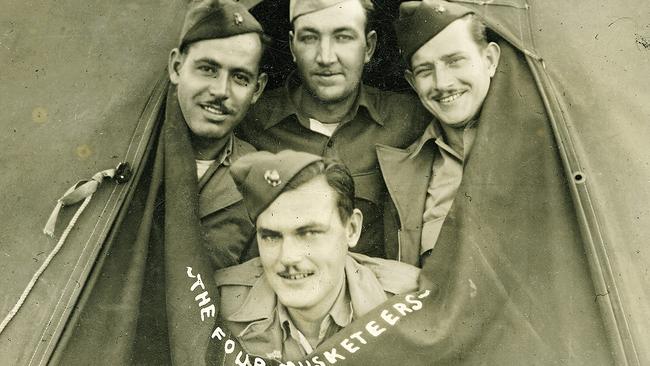

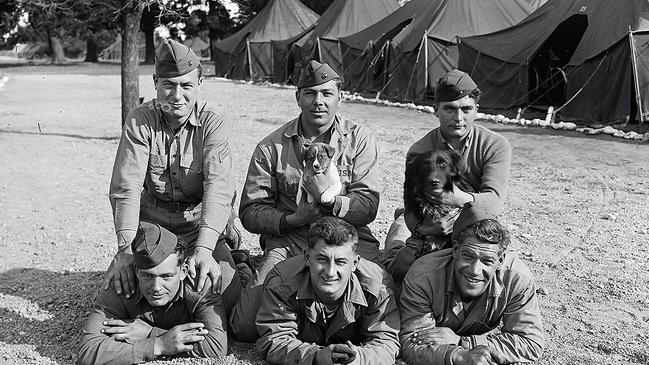

The US troop build-up was not confined to big cities. Between February 1942 and May 1943, up to 15,000 servicemen were stationed in Ballarat, which then had a population of 40,000.

VP DAY 75TH ANNIVERSARY: Get your free commemorative magazine in the Herald Sun tomorrow.

Ballarat Historical Society president Marion Littlejohn says the first 5200 troops were billeted in local houses for a short time while their camp at Victoria Park was completed.

“All this happened very quickly. February 19 was the Darwin bombing. Singapore fell on February 15. (General Douglas) MacArthur didn’t leave the Philippines until March 11. This was on the fly, ‘Oh my god, the Japanese are coming’. I think people were very glad they were here,” Ms Littlejohn says.

“They were courteous, helpful, kind and popular. People commented on their excellent teeth, neat uniforms and good manners. They jogged everywhere to stay fit.”

Professor Geoffrey Blainey, son of a Ballarat Methodist minister and now a historian, was almost 12 when the first Marines arrived.

“A lot of people we knew had Americans in their houses. I think my father was sick that week and we had four children in the house and no spare room, so we didn’t have an American. We were terribly disappointed,” Prof Blainey says.

“Their privates were dressed like our officers. The typical Australian private soldier didn’t look very grand in their uniforms,” he says.

“Their accents were strange to us. I wouldn’t have heard an American accent spoken in my presence.”

Ronald Gilbert, aged 11 in 1942, says he and his uncle Max, 2½ years his senior, spent many days visiting the camp.

“They treated us so well. I got bits of bomb shrapnel. They had playing cards and spotter cards for plane recognition. They gave us comic books. They’d get us a feed in the mess hall. They always had ice cream,” Mr Gilbert says.

“The camp was so clean. The tents were laid out in perfect straight lines, painted stones along the walkways. Everything was immaculate. And when they played Taps at the end of the day, every man just stopped and saluted the flag.”

The well-paid Americans “had money to burn”, Prof Blainey says, and sparked an economic boom.

Mr Gilbert’s mother washed the troops’ laundry, like many Ballarat women, while he helped Max in a shoeshine business.

Prof Blainey’s wife, Ann, recalls meeting Marines at Miss Brazenor’s tea rooms in Ballarat: “Miss Brazenor asked if we’d mind sharing our table with two American soldiers. They called my mother and grandmother ‘ma’am’. Their manners were impeccable … It’s stayed in my memory always. They were charming boys.”

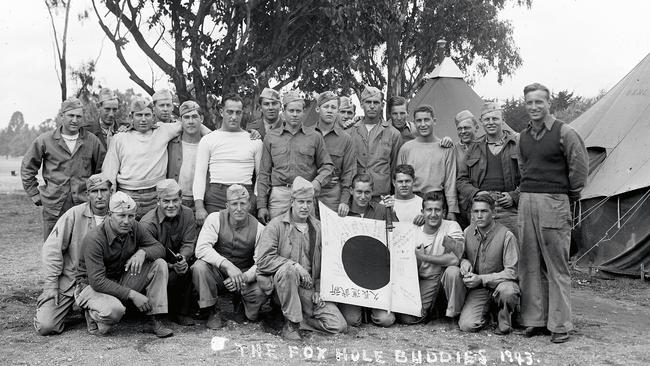

In January ’43, 1st Marine Division troops arrived to recuperate from the Battle of Guadalcanal (in the Solomon Islands) — many undernourished and suffering tropical diseases.

“They didn’t seem much older than me. They were all yellow from atropine (an anti-malaria drug that caused jaundice). They were pretty knocked around,” Mr Gilbert says.

Ms Littlejohn says many homes were open to troops on Sundays.

“People would take them to church, then home for Sunday lunch, and the boys would jog back to camp.

“People were a bit shocked because they ate with their fork, not their knife. We thought that wasn’t good table manners,” she says.

Then, without warning, the Marines left Ballarat in May 1943, singing the patriotic song Over There as they marched to the station.

The Marines continued training in Victoria, then rejoined the war in a series of decisive Pacific campaigns.

In some cases, the Ballarat connections lasted.

In 1986, while lecturing on a cruise ship, Prof Blainey met ex-Marines who visited friends in Ballarat on that trip. He says many people corresponded with troops and their families during and after the war.

Mr Gilbert says it was a special time in Ballarat.

“I will never forget those days and the times we spent wandering around the tents. They were gentlemen. They were good blokes, so kind-hearted.”

August 15 is the 75th anniversary of Victory in the Pacific Day, which marked the end of World War II. Get your free 24-page commemorative magazine in tomorrow’s Herald Sun.

MORE NEWS

HOW TO MARK THE VP DAY 75TH ANNIVERSARY AT HOME