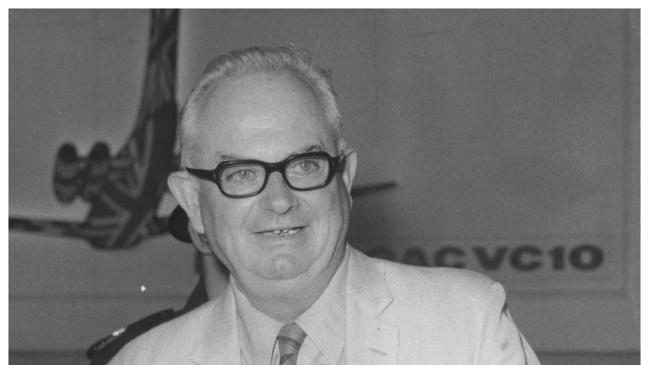

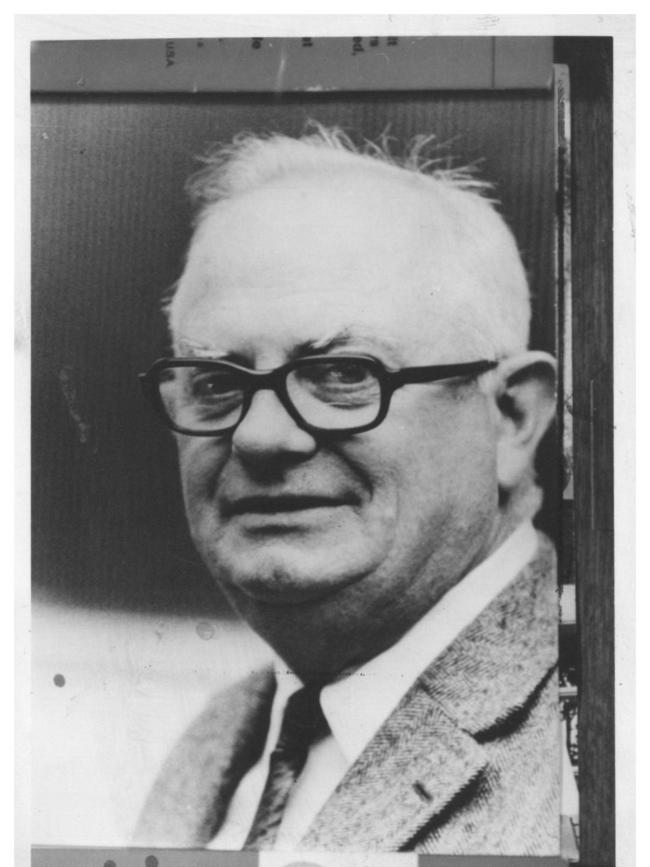

What Wilfred Burchett saw in Hiroshima 75 years ago changed the course of his life and opened the eyes of the world’s people to the realities of atomic warfare.

The journalist, born and bred in Victoria, wrote the first eyewitness account from Hiroshima’s only weeks after the first atomic bomb devastated the city on August 6, 1945 – 75 years ago this week.

The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki ended World War II.

Burchett’s revelations about the “atomic plague” suffered by survivors in Hiroshima showed the world the grim reality of the most powerful weapon the world had ever seen.

But Burchett is remembered by many as an Australian traitor because of his open support for

Communism through the Cold War.

Burchett was born in Clifton Hill on September 16, 1911, the youngest of four children, and spent his childhood in Gippsland and near Ballarat.

He studied at the Ballarat Agricultural High School, leaving school at 15 and working in a series of jobs including house painting.

But his lust for travel and flair for languages including French and Russian took him to London and a job with a Jewish travel agency, Palestine and Orient in 1937, where he married a German refugee, Erna Hammer, and helped to Jewish people escape the Nazi regimen.

With Erna, Burchett arrived in Australia in July 1939, warning newspapers about German

imperialism.

Burchett travelled to Asia in late 1941, reporting the Sino-Japanese War in China for London’s Daily Express and Sydney’s Daily Telegraph.

He was wounded in 1942 reporting the defeat of British forces in Burma.

The Daily Express sent Burchett to cover the Pacific war in February 1944, where his reports of conventional bombing campaigns against Japan were favourable.

He arrived in Japan with the first US troops and dozens war correspondents on a flight to Atsugi Naval Base near Yokohama in August 1945.

In his book An Eyewitness History of Australia, legendary Melbourne journalist Harry Gordon said while other journos made a beeline for Tokyo, Burchett hopped a troop train at great personal risk and made his way to Hiroshima for the last great scoop of the war.

His incredible story was published in The Daily Telegraph, the Daily Express and newspapers around the world on September 6, 1945.

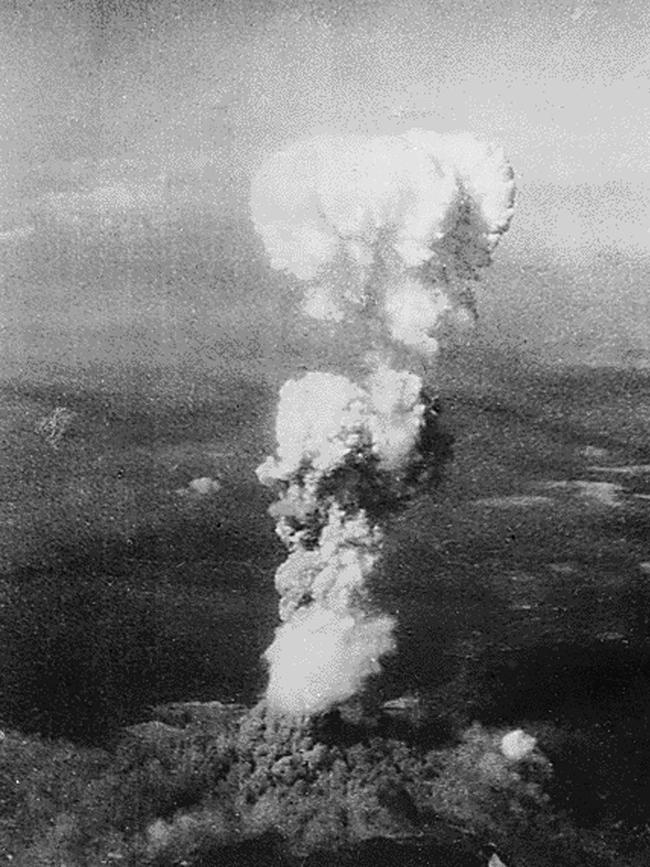

Burchett wrote: “In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation of four years of war reporting. Thirty days after the atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are dying mysteriously from its effects.

“People who were not injured in the explosion are dying from something unknown which could only be described as the atomic plague.”

He said Hiroshima “looks as though a giant steamroller has passed over and squashed it out of

existence”.

“It gives you a sick feeling in the pit of your stomach to see such man-made devastation,” Burchett wrote.

“I picked my way to a shack used as a temporary police station in the centre of the vanished city.

Looking south, I could see about three miles (4.8km) of reddish rubble. This is all that the bomb left of dozens of blocks city buildings, homes factories, and human beings.

”Nothing stands except about 20 factory chimneys with no factories. Looking west, there are half a dozen gutted ruins, then nothing for miles. The Bank of Japan is the only building ion the entire city, which had a population of 319,000.

“I saw people in hospitals who apparently suffered no injury, but are dying uncannily from the

effects of the bombing. For no obvious reason their health seems to fail.

“They lost their appetites, their hair fell out, and bluish spots appeared on their bodies. Then they began bleeding from their ears, nose and mouth.”

In latter stages, victims bled from their gums, vomited blood and died. The same fate befell Japanese medicos and scientists who came to help.

“That is one of the effects of the first atomic bomb dropped, and I don’t want to see any more,” he wrote.

Burchett’s story about the human toll of the A-bomb was heavily censored in the US, became a potent argument for atomic disarmament as the Cold War deepened in the years that followed.

It also changed Burchett’s view of American power.

In November 1945 he met Erna and their son in London, and he was soon posted to Berlin by the Daily Express.

Tom Heenan wrote for the Australian Dictionary of Biography that Burchett’s reports from Berlin – then divided between US, British and Russian forces – were often pro-Soviet and anti-American.

He divorced Erna in 1948 and, on Christmas Eve 1949, wed Bulgarian Communist Vesselina

Ossikovska in Sofia.

The couple travelled to Australia in 1950, where Burchett opposed prime minister Robert Menzies’ bid to ban the Community Party, a battle Menzies lost in the end, then Burchett reported glowingly from Mao Zedong’s Communist China in February 1951.

He filed on the Korean War from the North Korean side, and was accused of interrogating captured American pilots and a US General. Burchett was also a close confidante of Kim-Il Sung, North Korea’s first Communist ruler.

Burchett moved to Hanoi in 1954, where he met Communist leader Ho Chi Minh, and attended the Geneva talks that partitioned the Communist North from the democratic South in 1956 before moving with Vesselina to Moscow.

In 1962, he went to South Vietnam to cover the war from the Communist side, and headed to

Cambodia in 1965. By that time, he questioned the Soviet brand of Communism in favour of China’s.

He returned to Hanoi in 1966 on an American request brokered by the British Foreign Office for his assistance to repatriate captured US pilots.

Burchett was not successful but impressed the Americans and Brits enough that he regained his UK passport, although he remained barred from Australia despite numerous passport applications.

In 1968 he moved to Paris, where he assisted US-North Vietnamese peace talks.

In November 1969, Soviet defector Yuri Krotkov named Burchett and others as KGB agents before a US Senate hearing.

Burchett re-entered Australia on a private plane from Noumea in February 1970. The government tried to have him charged with treason but with little evidence by 1972, he was granted an Australian passport.

In 1971, strident anti-Communist Democratic Labor Party senator Vince Gair accused him in

parliament of being a KGB operative, a claim repeated in DLP newspaper In Focus by publisher Jack Kane.

Burchett sued and won, but because Gair had parliamentary privilege, the court awarded costs

against Burchett. The debt forced him to leave Australia again.

He reported revolutions in southern Africa and weakening Socialist ideals in China.

Although he initially praised Pol Pot’s regimen, the Khmer Rouge placed him on a death list for his reports about genocide in Cambodia.

He settled in Sofia, Bulgaria in 1982, and died there on September 27, 1983 survived by Vesselina, a daughter and three sons.

Rowan Callick wrote for the Melbourne Press Club that Burchett’s New York Times obituary

described him as: “an Australian journalist who for decades functioned as a Western spokesman for Communist regimes in Asia and Europe”.

He was so revered in Vietnam that in 2011, the centenary of his birth, an exhibition in his honour was held at Hanoi’s Ho Chi Minh Museum.

Using KGB papers retrieved from Soviet files in the late 1990s, Professor Robert Manne of La Trobe University revealed in The Monthly in 2013 that Krotkov, Gair and Kane were right all along – the Soviet Central Committee agreed in 1957 to pay Burchett a sum of 20,000 roubles, with a 3000 rouble-a-month salary, to act as a KGB operative.

Despite the controversy about his post-World War II career, one thing is certain – Wilfred Burchett’s reportage from Hiroshima helped to change the world – a fact recognised when the Melbourne Press Club admitted him to its Australian Media Hall of Fame in 2014.

MORE NEWS

HOW ANN SHIELL BECAME MELBOURNE’S FEARED SLUMLORD QUEEN

ECCENTRIC SOCIALITE WHO KEPT PET CHEETAH WITH DIAMOND COLLAR

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout