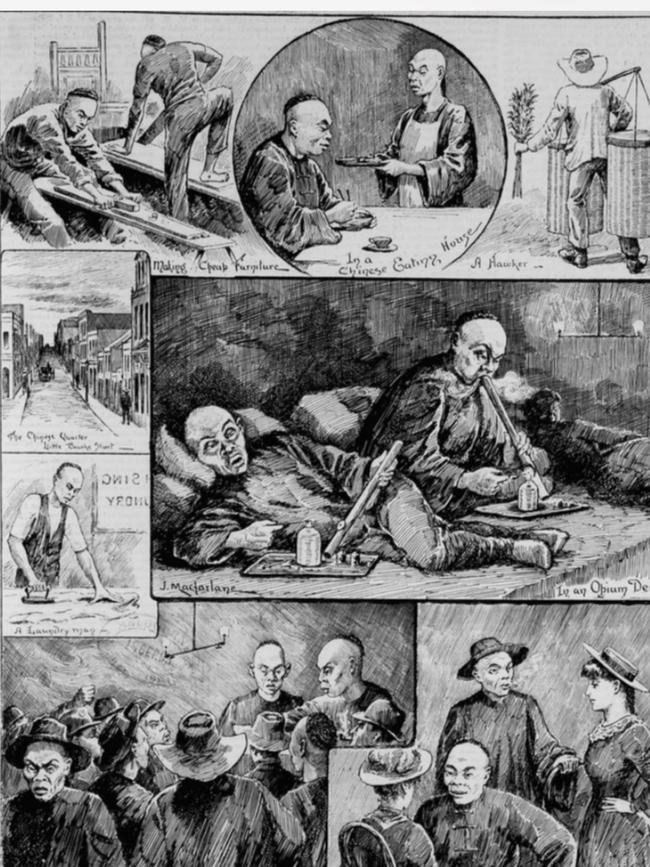

Opium dens were rife in Victoria’s gold rush, luring young women to ruin

As the opium boom transformed Victoria’s colonial goldfields into a ramshackle maze of smoke-filled dens, hatred began to grow for the foreign drug as it lured young women to a life of addiction.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In the winter of 1870 a stranger walked into the Chinese camp at Ballarat.

The camp, which lay between the gold diggings and the Main Road, had once been a gathering of tents and campfires.

More than a decade after gold had drawn thousands of Chinese to the colony of Victoria, it was now a village of ramshackle, dark buildings.

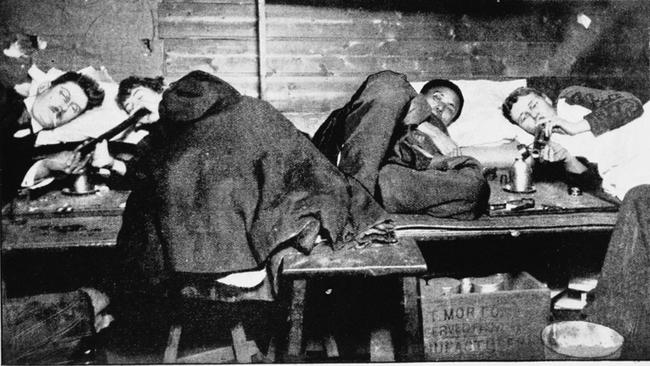

The stranger entered a shabby doorway to a long corridor, thick with choking smoke.

On either side, narrow doorways covered with curtains led to tiny rooms where Chinese men sat or lay on wooden couches.

Some were unconscious, some were cheerful, but all were smoking from long, thin pipes.

The stranger progressed down the passage to where two Chinese men sat outside a particular room.

Behind the curtain lay two fair-skinned European girls, each about 15 years old, sprawled on filthy bedding and delirious on the drug that had swept the colony and was now threatening its destruction.

Opium.

The unknown man’s account, published in the Ballarat Courier in 1870, described methodical visits to every known opium den in the town.

The youngest female victim he found was just 13.

As the anti-Chinese sentiment that began on the goldfields spread, so too did hatred for this new foreign drug and the foreigners who were luring young Victorians to a life of addiction.

THE LOST GIRLS

By the late Nineteenth Century, Chinese villages in rural centres around the colony were riddled with opium dens.

As the gold rush waned and its Chinese migrants realised their dreams of wealth would never materialise, drug use skyrocketed.

The Salvation Army publication War Cry said of the Chinese villages in 1884:

“In these Camps vice and infamy are to be seen daily and hourly in their very blackest forms. Here brothels, gambling-houses, and opium-dens are in fall swing, unheeded and unchecked by the authorities, whose business it is to put down such places, and God knows, if any places in the colony should be suppressed and rooted out it is these Chinese Camps, for it is in them that so many of our Victorian girls are brought to ruin.”

And girls were indeed being brought to ruin.

Disturbing tales were emerging from Melbourne to Maryborough of teenage girls being lured to the camps with trinkets or clothes, often by other women of European descent, and offered a puff of opium.

Accounts tell of the girls who fell unconscious almost immediately and, when they woke, discovered they had been sexually assaulted.

The opium high was followed by an excruciating melancholy lasting hours, causing the hapless girls to keep smoking the drug and, for many, begin a pattern of addiction and prostitution that separated them permanently from their families.

The Salvation Army had been undertaking a series of daring raids on camps around Victoria, effectively abducting opium-addicted teenage girls and either returning them to their families or housing them in what would now be called rehab clinics.

The girls kept company with criminals of every variety to whom opium dens were a safe haven.

By the end of the century there was wide public support for an opium ban.

But criminalisation was partly hampered by the extensive use of opium in medicine, especially as a remedy to period pain and depression.

CLEVER SMUGGLERS

Despite widespread calls to ban opium, government restriction of the drug before federation was limited to a high import excise and labels warning against an overdose.

By the 1880s a leading Chinese figure in Melbourne known as Quong Tart made a public campaign to end opium importation entirely.

But the ingenuity of Chinese opium peddlers was a force to be reckoned with.

To dodge the high excise and multiply profits, opium was concealed in just about anything coming from China to Australia.

One account in the Melbourne Argus in 1884 describes:

“Sometimes the thick soles of the Chinese slippers are hollowed out, and the cavity filled with opium, and at others it is cleverly hidden in the centre of pack-ages of Chinese goods.”

There were also fears that a ban on opium would cause the trade to move swiftly to an efficient underground operation:

“The best proof of the difficulties that may be expected in such a gigantic undertaking as securing the abolition of its use have been afforded when opium eaters were imprisoned for any offence. All their ingenuity has been exercised to obtain a supply, and the police believe that in nearly every case they have been succcssful.”

Police believed the opium use among the Chinese community of more than 10,000 people was almost universal.

But by 1905, with the gold rush long gone and the Chinese population declining, tighter legal controls on opium were introduced.

Opium dens persisted in Melbourne, especially on the popular Chinese village on Little Bourke St.

In the early Twentieth Century, police inspectors were resorting to using ladders to climb directly to the first storey window of suspected opium dens to find addicts mid puff.

Despite the criminalisation of opium and the gradual preference for other narcotics, opium dens in Melbourne existed until the 1950s - a habit that spanned 100 years.

MORE NEWS:

US PROTESTS: WHAT ‘DEFUND THE POLICE’ REALLY MEANS