Did Melbourne keep news of the discovery of gold a secret from Sydney?

Melbourne in the 1850s became rich as rivers of gold flowed from Clunes to Beechworth. But a little-known coincidence points to a secret that might just have kept the gold from going straight to Sydney instead.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

The gold rush made Melbourne mega rich.

In the late 1800s than a third of the world’s gold was coming out of Victoria.

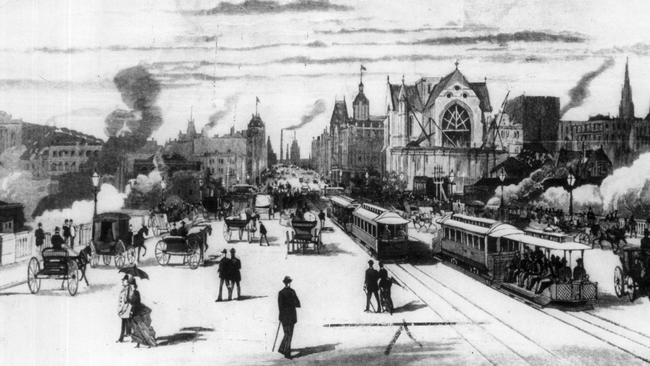

The population of Melbourne grew from 25,000 to half a million in just a few years and the city became one of the wealthiest in the world.

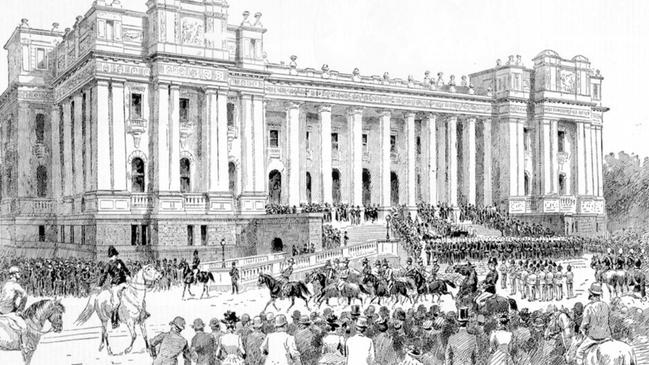

For decades afterwards, grand public projects were funded by the rivers of gold.

Parliament House, the State Library, Old Treasury and what is now the Princess Theatre were bankrolled.

But a little-known coincidence points to a potential golden secret that kept the gold from going straight to Sydney instead.

Just weeks before the discovery of gold was made public, Melburnians finalised a deal to separate from New South Wales.

Some say we knew about the gold. And we weren’t saying a damn thing.

MELBOURNE, FOUNDED IN NEW SOUTH WALES

Melbourne was founded in New South Wales.

From 1835 until 1851 Victoria didn’t exist and the area around Melbourne was known as the Port Phillip District of New South Wales.

Charles La Trobe was made superintendent of the district and later became Victoria’s first lieutenant-governor.

By the early 1840s Melbourne wasn’t in great shape.

Cost of living was high and regulation from Sydney caused banks to charged up to 12 per cent on loans.

The lack of a sewerage system meant raw effluent ran in torrents in open drains, a horror that later earning the city its nickname Smellbourne.

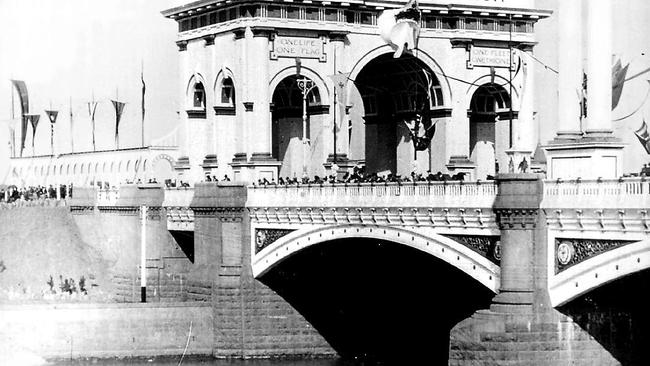

Many Melburnians blamed their malaise on Sydneysiders, with constant bickering over funding for important projects, including Melbourne’s new Princes Bridge.

The Port Phillip district eventually had enough.

Plans were underway since about 1840 to sever ties with the meddling and mismanaging New South Welsh.

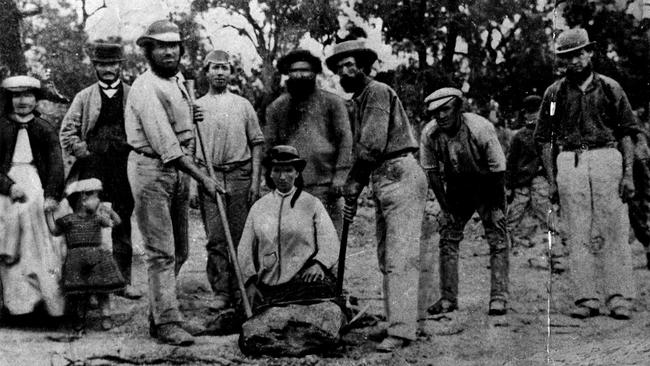

More than 10,000 settlers were now in the Port Phillip District and over the next decade the population of Melbourne alone would reach tens of thousands.

An early petition to the Crown in 1842 failed to secure separation and another attempt in 1846 saw Port Phillip residents able to vote for extra seats in the New South Welsh parliament.

After ten years of lobbying, backlash from Sydney and at times indifference from the Crown, Victoria won its existence.

When the news arrived in Melbourne, four days of holiday celebrations were declared.

Victoria was born on July 1, 1851.

But there was something happening behind closed doors that gave some Melburnians extra cause to celebrate.

ESMOND’S GOLDEN SECRET

In 1850 James Esmond, an Irish prospector with experience on the Californian goldfields, breezed in to try his luck in what was then the Port Phillip District.

Small discoveries of gold fragments in quartz had been made in central Victoria since the 1820s and Esmond narrowed in on an area near Clunes.

By July 5, four days after Victoria became independent, news of a few ounces of gold being extracted from Esmond’s site had reached the Geelong Advertiser.

But it might not have been a coincidence.

It was rumoured that Esmond had known about gold around Clunes for several months and had kept it secret.

He knew the Port Phillip District was soon becoming independent and some believe he was holding out.

New South Wales had imposed tight regulations on prospecting including the collection of fees for mining licenses.

But under the new colony of Victoria, fewer obstacles would be in Esmond’s way.

He declared June 28 1851 as the official date of his gold discovery and, what a happy coincidence, it took three days for word to reach Melbourne.

That meant July 1 might have been the day that Victoria was released from the clutches of New South Wales, and the day rumours about paddocks full of gold were spreading like wildfire around the new colony.

The extent to which the authorities, including La Trobe, knew about the gold is unclear.

But how sore those Sydneysiders must have felt when, within months, the gold rush had swept Victoria in an unprecedented boom that would last almost two decades.

GOODBYE SMELLBOURNE

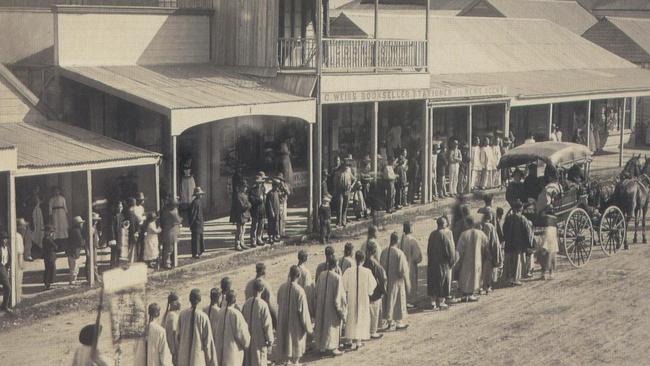

Gold was soon struck in Castlemaine, Beechworth, Ballarat, Bendigo and Daylesford as thousands of migrants poured in.

Two tonnes of gold per week were rolling into Treasury on Spring St.

READ MORE: MELBOURNE MYTHS AND URBAN LEGENDS

In 1856 alone almost 95,000kg of gold was pulled from diggings in Victoria.

Within a decade the old Smellbourne name was cast aside and rivers of excrement turned to rivers of wealth.

Melbourne became the centre of Australian life and the most important city in the empire outside London.

From Smellbourne to Marvellous Melbourne.

The CBD is still lined with grand buildings erected during the gold boom.

We’ll never know how close we came to handing the riches to Sydney instead.

Mitchell Toy is a Melbourne artist and writer.