Crime and debauchery: The dark past of Melbourne’s laneways

MELBOURNE’s laneways were once hidden hollows for crime and debauchery. But what began as a haven for criminal activity has become one of our city’s greatest treasures.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

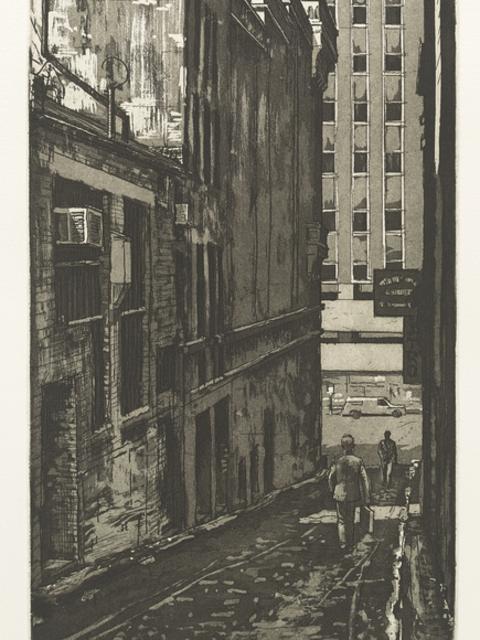

THEY were once the filthy back door of elite establishments, where garbage and sewage festered and deliveries were made.

Melbourne’s laneways were hidden hollows for crime and debauchery, with secret entrances to brothels, adult book shops and massage parlours.

Once dangerous destinations, they have since been transformed into our city’s greatest treasures, boasting bars, restaurants and street art.

But Melbourne’s laneways weren’t always a Mecca for culture. They began simply as service lanes after Robert Hoddle designed the CBD in 1837.

“It was part of organising the Hoddle Grid plan,” Museums Victoria curator Michael Reason said.

“They were large blocks and people realised they would need access to the back of their properties.

“Laneways were for rubbish, sewerage collection, some were privately owned — they were almost part of the property. And they were where all the things happened that you wanted out of sight. Over time they attracted undesirables, criminals.”

Two particular laneways side-by-side were a haven for criminal activity in the 1870s — Romeo Lane and Juliet Terrace.

Home to Melbourne’s red light district, one was for the ladies and the other for the gents of the night.

Little more than 100m long, the pair of star-crossed laneways led to Bilking Square, named after the practise of sex workers bilking, or stealing, from prospective customers.

The “disorderly behaviour” — as described in a January, 1871 edition of The Argus newspaper — became so bad that plain clothed police swept in to investigate. In a single day, almost 50 people were arrested.

Among the “thieves, bullies, and women of the town of the lowest class” was Ellen Donovan, better known as the “Bull Pup”.

The Argus described her as someone “so ugly now, being a squat ... woman, about 4ft high, and nearly as broad”.

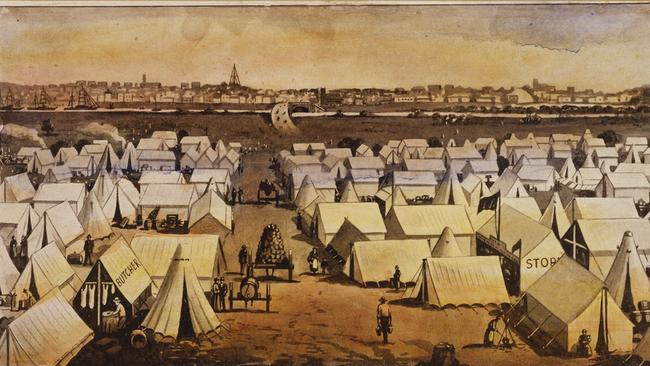

But the Bull Pup had once been queen of the underworld of Canvas Town, the tent city built during the gold rush at South Melbourne in the 1850s.

“For a long time (she) fascinated the hearts of lucky diggers, whose gold she easily obtained, and more easily squandered,” the Argus wrote.

Further attempts were made to clean up the laneways and Bilking Square was demolished.

Romeo Lane was renamed Crossley St — where a bar now stands, taking its name from the historic laneway — and Juliet Terrace was called Liverpool Street.

The pair are now filled with galleries, shops and trendy restaurants which are far removed from their debaucherous past.

Not far away, another laneway flesh trade was making its mark on Melbourne. Horseflesh.

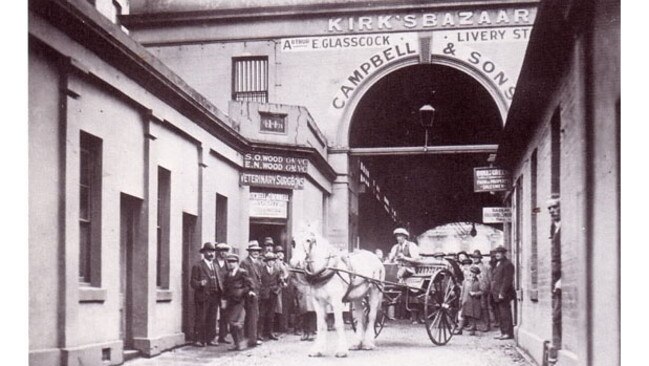

Kirk’s Lane, now Hardware Lane, was the centre for the city’s bloodstock industry in the mid-1800s.

Racehorses were bred and trained at Kirk’s Horse Bazaar, named after owner James Bowie Kirk.

Each week, buyers drove to the city’s most famous bazaar where hundreds of horses would be auctioned.

The cobblestone alley, with its umbrella canopy and live music, is now unrecognisable from the strip where horses were once trotted out for potential buyers.

Now, those ambling down Hardware Lane will find Kirks Wine Bar on the corner at Little Bourke St, where a shoeing forge once stood.

A nearby lane dealt in a different trade of rags rather than flesh.

Little Flinders Street — now named Flinders Lane — was the strip for the garment industry.

Warehouses stood along the laneway and at its peak, there were more than 600 clothing firms in the 1940s.

Over the next three decades, many of them left as rents continued to rise. Adjoining Hosier Lane was also part of the clothing district.

The narrow alley had a men’s clothing warehouse and costume manufacturer.

It wasn’t until recently that the nondescript concrete alley was transformed into the vibrant and iconic destination for Melbourne’s street art.

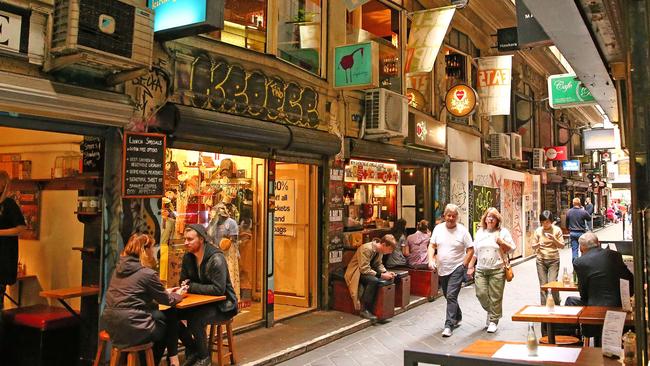

Same too went for Degraves St and nearby Centre Place.

Initially, they were thoroughfares often filled with parked cars. Later, they were filled with shops.

It wasn’t until the 21st century they became hubs for food and bar culture. But that happened by accident.

When Crown Casino was being developed at Southbank in the 1990s, there were plans for bars and restaurants along the Yarra River.

Casino owners feared operating under a single liquor licence — one incident of bad behaviour and the whole venue could have lost its liquor licence.

So, under then-Premier Jeff Kennett, the government introduced a “small bar” licence, which allowed tiny watering holes to sprout through the city’s laneways.

“The numbers basically quadrupled in a 10 to 15 year period,” Mr Reason recalled.

Melbourne’s historic laneways have turned from trash to treasure, and whether it’s a wander down Degraves or Drewery or even Dame Edna Place, there’s one thing that can be said for all of them.

“Stepping into a laneway feels like going back in time,” Mr Reason said. “It’s like reaching into the past — that’s what people love about them.”

ACDC Lane

Formerly Corporation Lane in the centre of the city’s rag trade, it was renamed as a tribute to Aussie rockers AC/DC in 2004.

Centre Place

The go-to destination for a sensory overload and the quintessential Melbourne laneway.

Covered in art, crammed with coffee shops and always bustling with the hungry lunch crowd.

Dame Edna Place

Formerly Brown Alley, the dead-end lane was renamed after comedian Barry Humphries most famous character in 2007.

Degraves Street

Home of William Degraves’ steam flowermill, it was originally named after pioneer merchants Charles and William Degraves.

Flinders Lane

Originally Little Flinders St and the centre of Melbourne’s rag trade, now a thriving strip filled with restaurants and boutique shops.

Hardware Lane

Originally Kirk’s Lane on a former horse and livery trading centre named Kirk’s Horse Bazaar, now filled with bars, umbrellas and jazz.

Hosier Lane

Street art now covers the concrete walls of this laneway, once just the backdoor of prominent buildings.