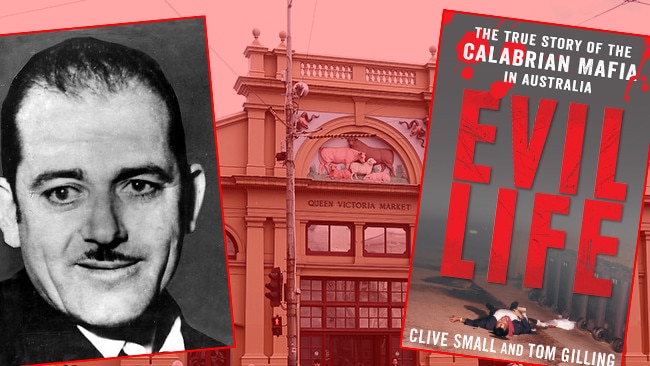

Behind the 1960s Queen Victoria Market Calabrian mafia wars

IN 1963, two shotgun blasts in Northcote heralded the start of a deadly battle as mafia families fought for power, revenge and control at the Queen Victoria Market.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

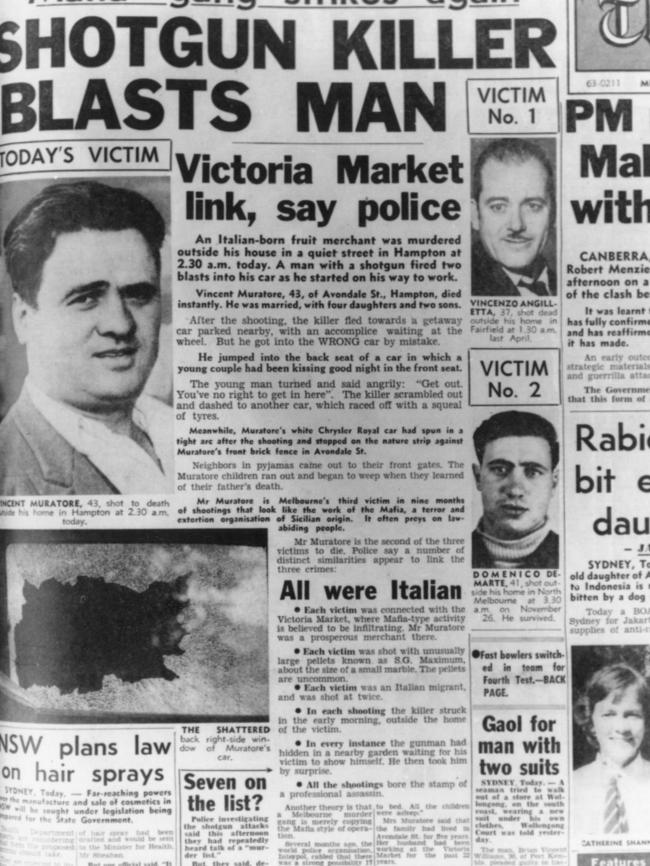

BY the early 1960s Calabrian migrants had a stranglehold on business going through Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market. With an annual turnover of between $40 million and $50 million, almost entirely in cash, the market was a lucrative target for the Calabrian mafia. In 1963 the long-running power struggle for control of market extortion rackets exploded onto the streets with two murders and two attempted murders.

HOW MELBOURNE BECAME A MAFIA STRONGHOLD

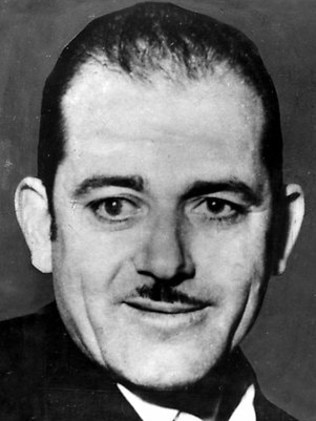

On 4 April, the 47-year-old mafia boss Vincenzo Angilletta was killed by two blasts from a double-barrelled shotgun as he parked his car at his home in the Melbourne suburb of Northcote.

His 17-year-old son, Francesco, who was in the house when he heard the blasts, ran to the car and found his father dead at the wheel. Francesco saw that his father’s head was covered in blood and noticed blood on the seat and floor of the car. The rear window was shattered.

Francesco later told police he had taken his father’s pistol from under the front seat before the police arrived and had buried it in a poultry pen. The pistol was recovered by police.

Vincenzo Angilletta had migrated from Gioia Tauro, Calabria, to Melbourne 12 years earlier as a 35-year-old. He had a criminal record in Calabria that went back to 1934 and included convictions for weapons offences, black marketeering and ‘robbery and complicity’, for the last of which he had served five years’ jail. He and ten other men armed with submachine guns had been terrorising and robbing Italian villages. Angilletta and his three brothers were considered by Italian police to be members of the local mafia in Gioia Tauro.

Angilletta’s relatives immediately plotted revenge for his murder. According to Dr Ugo Macera, who was helping the Victoria Police investigate Italian organised crime during the mid 1960s, the hit had been ordered by Melbourne godfather Domenico Demarte, his associate Vincenzo Muratore and some others. Angilletta ‘had been sentenced to death at a meeting held in a secluded room of the Bonanza Bar in Union Road, Ascot Vale’. The reason for the murder was some irreconcilable difference with the Calabrian L’Onerata. One source suggested this difference was over Angilletta’s ambition to replace Demarte as leader; another that it concerned the distribution of extortion money from the Queen Victoria Market.

TOMATO TIN MAFIA: BEHIND THE WORLD’S BIGGEST DRUG BUST

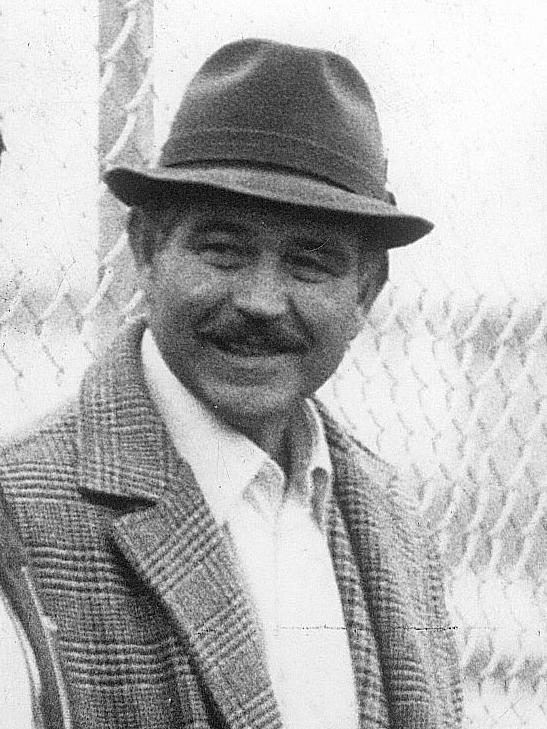

After his migration to Australia in 1938, Domenico Demarte had been quick to establish a reputation for violence. He had married a niece of Domenico Italiano — the original Melbourne godfather — and had risen through the ranks, becoming a godfather himself in the late 1950s.

Vincenzo Muratore had also migrated to Melbourne in 1938, as a 17-year-old. He had no criminal record in either Italy or Australia, but was known as a tough and unscrupulous businessman. After Italiano’s death of natural causes in 1962 Muratore is thought to have become the Society’s accountant in Victoria under Demarte’s leadership and to have sponsored the migration of at least 14 suspected Society members to Australia.

Two months after Vincenzo Angilletta’s assassination a meeting was held on the property of Giuseppe Carbone at Buronga, New South Wales, near Mildura. Carbone was born in Calabria in 1920 and had a criminal record there that included theft, possession of prohibited weapons and robbery with violence. He arrived in Melbourne in 1949 and established his reputation as ‘an arrogant standover man’. He quickly gained connections with the mafia bosses in Victoria and New South Wales, and his property was frequently used during the 1950s and 1960s for Society meetings.

His sister was married to Domenico Demarte. Despite Carbone’s prominence in the Society’s activities over two decades — four active mafia branches were identified in the Mildura area during Carbone’s leadership — he was able to keep a relatively low profile. In the late 1960s he fell out of favour with the Society’s broader leadership and his role gradually declined, but he had played a significant part in strengthening the ’ndrangheta and still exerted influence with the Society’s leadership in the early 1980s.

The meeting at Carbone’s property in mid 1963 was attended by ’ndrangheta bosses from Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney, Griffith and several other country towns across New South Wales. It is known that the topic of the meeting was Angilletta’s murder and its implications for the leadership of the Society. Three months later Carbone travelled to Calabria ‘for instructions’. Following his return to Buronga, another meeting was held and action was taken to implement the decisions.

HOW THE 1960s MAFIA MURDERS LINKED TO CALABRIAN CRIME

In November 1963, seven months after the assassination of Angilletta, Domenico Demarte was hit by a shotgun blast as he left his North Melbourne home and walked towards his car. ‘I fell to the gutter,’ Demarte told the police. ‘I started to scream.’ Demarte was admitted to hospital and underwent several operations. Typically, he did not see who had shot him and claimed to have no enemies.

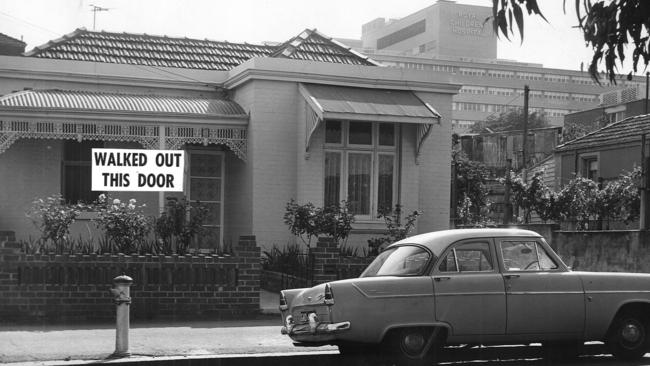

Several weeks later Vincenzo Muratore was killed when an assassin fired two shotgun blasts through the back window of his car as he drove out of his home in the bayside suburb of Hampton. After the murder, Muratore’s family received a letter from a Calabrian family connected with the Queen Victoria Market, from whom Muratore had been extorting money.

John Cusack reproduced the letter in his 1964 report on organised crime in Australia:

Muratore family:

I do rite this letter in English as I

Want your kids to read your rotten old man robed

My father in the market. You did live good with

Money you robed from us in a good house when we are

Poor through you and we work hard.

Take your kid in Calabria when you was poor

And living like a dirty rate when you had nothing

and was poor to.

Go back to Calabria and live like a dirty

criminal as you and your kid are.

But no go in the market and rob like your father

did from poor family like us.

Take your kid in Calabria when you was poor

[signed] One whose family was robbed by you.

Around the time the letter was received, about 400 Calabrians — many from Mildura and interstate — called at Muratore’s home to offer condolences to his family.

Two days after Muratore’s murder, a trader at the Queen Victoria Market, Antonio Monaco, was wounded by a shotgun blast as he left his small vegetable farm in Braeside, about 25 kilometres southeast of Melbourne. Monaco had a reputation as ‘a tough [guy] and a man with a violent temper’. He had been trying to avoid paying the Society a commission on the vegetables he sold through the market.

Monaco arrived in Melbourne in 1950 as a 26-year-old. He had been ‘denounced and arrested’ in Calabria for ‘complicity in murder’ and ‘attempted double murder’, and convicted of robbery with violence and other crimes. His elder brother, Saverio, followed him to Melbourne in 1951.

Saverio had a long history of arrests in Calabria for crimes including wounding, complicity in murder, threatening violence and affray. In 1953 he was charged with the attempted stabbing murder of a man in Canberra; he beat the charge but was deported to Italy.

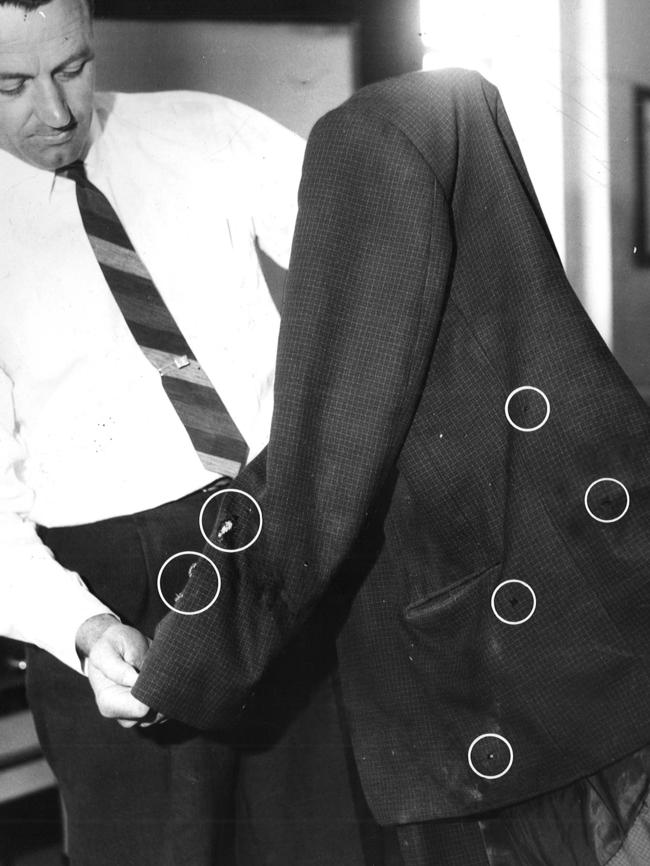

In June 1964 another plot to ‘finish off’ Monaco was uncovered and stopped by the Victoria Police. Three men were charged with conspiring to murder Monaco: 41-year-old Francesco Tripodi, who was married to Monaco’s sister-in-law; Tripodi’s 24-year-old brother, Salvatore; and 24-year-old Salvatore Trimboli. At the trial in late 1964, the prosecution claimed that the police had seized £1600 in cash from Salvatore Tripodi and Trimboli, which was to have paid for Monaco’s murder. (It was also claimed that a £50 ‘deposit’ had been already paid.)

A witness, Giuseppe Capanni, gave evidence that in the months before Monaco’s shooting Trimboli had been looking for a gunman. On one occasion Trimboli had said to Capanni, ‘Why don’t we do this job?’ On another occasion Trimboli had told Capanni that ‘there was £2,500 for the killer as soon as the man died’.

Capanni had pretended to be willing to do the job himself but was really planning a doublecross. He had already told the police about Trimboli’s offer and they were watching Trimboli’s every move.

The prosecution alleged that the shooting and wounding of Monaco had been carried out by Francesco Tripodi, and that he had admitted to it, claiming to have hidden near Monaco’s home and shot him from a distance of 35 paces. Despite Tripodi’s admissions and the evidence of Capanni, all three men were acquitted of conspiring to murder Monaco. Francesco Tripodi was jailed for two and a half years for Monaco’s wounding.

In November 1964 Vincenzo Angilletta’s 21-year-old illegitimate son, Carmelo Arfuso, stood trial for the murder of Vincenzo Muratore. Arfuso lived with his mother, Carmela Maria Concerta Arfuso, at Preston, just north of the city. Angilletta’s wife, with whom he had seven children, lived nearby; Angilletta seems to have lived between the two households. He had brought Carmela Arfuso to Australia in the early 1950s. Back in Italy she had been convicted of attempting to kill a man who had rejected her affections and had been sentenced to three and a half years’ jail. She had then married Antonio Scuttella who, a week after the wedding, had been sentenced to 26 years’ jail for murder.

The prosecution alleged that Carmelo Arfuso had conspired with the murdered Angilletta’s nephew, 43-year-old Francesco, who had arrived in Melbourne from Calabria in 1959, and 21-year-old Angelo Demarte to kill Muratore. They blamed Muratore, along with Domenico Demarte (no relation to Angelo), for Angilletta’s murder.

After fleeing to Calabria, Francesco Angilletta had made a confession to the Italian police. It had been agreed, according to his statement, that he and Angelo Demarte would kill Domenico Demarte and that he and Arfuso would kill Vincenzo Muratore. Francesco said that he later drove Arfuso to Muratore’s home, where Arfuso shot him.

He described how Arfuso had run from the scene and jumped into the wrong car — two lovers were kissing goodnight in the front seat — before realising his mistake. Arfuso jumped from that car and seconds later was picked up by Francesco, who was driving a similar car slowly down the street. After hearing Francesco’s confession Arfuso allegedly told the police: ‘I have already said it was true. I didn’t want to admit this crime. I am a good Italian boy. I was very upset by my father’s death.’

Francesco also claimed in his statement, which was read to the court, that his uncle had been shot for attempting to bypass the commission agents when selling his produce at the market. According to John Cusack, Vincenzo Angilletta had done this by making it a practice to sell his farm produce directly from his own vehicle at the Victoria Produce Market rather than from a market stall. This was the subject of an argument that had taken place a few months before his murder, during which Angilletta had been stabbed.

Despite Francesco’s confession, Arfuso’s alleged admissions to the police and the evidence of the lovers in the car, the jury took just four hours to acquit Arfuso. Ninety minutes later he was arrested and charged with conspiracy to murder Domenico Demarte, but once again he was acquitted. It was not the last charge Arfuso would face.

In 1965 a Melbourne court dismissed a charge against him of the 1963 shooting and wounding of Antonio Violi, who had arrived in Australia from Platì in 1952 as a 19-year-old. After the shooting, Violi had fled to Calabria to avoid giving evidence.

In December 1964 Angelo Demarte faced trial for the attempted murder of Domenico Demarte. By now Angelo had married Vincenzo Angilletta’s daughter. The prosecution claimed that he had admitted shooting Domenico Demarte to avenge his father-in-law’s murder. Angelo, the prosecution alleged, had been the driver while Francesco Angilletta had fired the shots.

The court was told that Domenico Demarte and others had wanted Vincenzo Angilletta killed and that Calabrian tradition required Angelo, as the eldest male member of the family, to take revenge.

Asked by police why Angilletta’s other son-in-law Antonio D’Angelo, the eldest male member of the family, had not carried out the killing, Angelo replied: ‘He was too weak, he ran away to Italy and left his wife here.’ D’Angelo later returned to Melbourne and told the court that he had fled Australia to avoid responsibility to ‘vindicate the blood’ of his father-in-law.

Domenico Demarte stuck to the story that he had no enemies and insisted he was ‘good friends’ with Angelo Demarte. It is hardly surprising that after a week-long trial the jury was unable to reach a verdict.

At a retrial eight months later Angelo Demarte denied any involvement in the shooting and said that he only learned of it from a customer in the espresso bar where he worked. Again the jury could not reach a verdict. There were no more trials for Angelo Demarte.

Francesco Angilletta spent nearly three years in Palmi’s jail before being returned to Australia. In 1967 he was acquitted of the murder of Vincenzo Muratore and the attempted murder of Domenico Demarte. Angilletta told the trial judge that his confession had been beaten out of him by Italian police — a claim the police denied.

Two years before Francesco Angilletta’s acquittal the police chief in the province of Reggio, Calabria, was suspended after Australian documents concerning the 1963 killing of Muratore were seized in his office. According to a 1965 AAP Reuters report, the magistrate investigating Angilletta in nearby Palmi ‘had been waiting for a long time for the seized documents’, but they got no farther than the ‘police chief’s office’.

The report quoted the Turin newspaper La Stampa as saying that the suspension of the police chief was a ‘very grave matter’ and indicated there was a ‘new type of mafia’. ‘For the first time in the history of Italy a sequestration has been carried out of judicial documents in the very office of a police chief,’ La Stampa reported.

From a police point of view the Victoria Market murder prosecutions had ended in failure, with nearly all of those arrested beating the charges in court. Nevertheless, the police crackdown succeeded in putting a temporary stop to mafia shootings.

The same pattern of mafia infiltration and exploitation of produce markets was repeated in Sydney, with the same violent results. In the late 1960s resistance to the ’ndrangheta’s extortion of ‘commissions’ from growers led to a spate of firebombings in Sydney’s western suburbs, at least three of which occurred in Fairfield. In one incident a firebomb was thrown through the window of a house to ignite a 4-gallon drum of petrol inside. The subsequent explosion hurled the back door more than 150 metres and reduced the house to ruins. The house was empty so nobody was injured — but the attack sent a powerful warning.

Detectives from the New South Wales Special Branch, Criminal Investigation Branch and local stations raided homes and arrested suspected Society members. Guns, explosives and stolen property were seized and seven men, all Calabrians, were charged with a variety of offences. All denied involvement in and any knowledge of the attacks. None knew anything about a secret Society. For a while the firebombings stopped.

John Cusack’s 1964 report to the Victorian Government was initially withheld from federal and other state authorities. However, the Commonwealth received a warning about mafia activities in Australia from another source. According to Bob Bottom in Shadow of Shame (1988), ‘At the same time [Interpol] passed on a warning to Australian police that mafia organisations were operating in Sydney and Melbourne. Italian police had briefed Interpol after monitoring a Rome summit meeting of the international heads of the mafia, held to plan a complete reorganisation of overseas racketeering.’

In September 1965 New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory police raided the homes of suspected senior Calabrian mafia members in several cities and towns. One of the homes raided in Griffith was that of Pietro ‘Peter’ Callipare, a suspected local Calabrian godfather, in both the political and the criminal sense. A letter from the Melbourne godfather Liborio Benvenuto was found in Callipare’s home. (Benvenuto later escaped an attempt on his life when his four-wheel-drive was blown up at the Queen Victoria Markets in May 1983. He died of natural causes five years later.) Benvenuto’s letter referred to a meeting to be held to ‘confirm our brothers’. Another handwritten document contained a list of Society members from Melbourne and from Mildura in northwest Victoria. A similar document was found at a house in the western Sydney suburb of Smithfield. Callipare and others were arrested and charged with a number of firearms offences.

Two days after Callipare’s arrest in Griffith, the local MP, Al Grassby, told the New South Wales Parliament: ‘I can testify now and will continue to do so that [Callipare] was a good neighbour to all people in the community, and I shall defend him or anyone else who is maligned.’ Grassby, who had been elected for Labor with the help of the Calabrian vote, later gave character evidence for Callipare, as did John Kenneth Ellis, the local Detective Sergeant. As a result, Callipare escaped with a $40 fine.

As well as uncovering evidence of close links between ’ndrangheta cells in Sydney, Melbourne and various country towns, the 1965 police raids found information about mafia membership, meetings and rituals. Some of this confirmed what was already known. Two years earlier Victorian police searching the Preston home of Francesco Angilletta had found four pages of typewritten notes in Calabrian dialect describing an ’ndrangheta initiation ceremony. When questioned about the document, Angilletta claimed to have copied it from a newspaper. Reminded that he was barely literate and could not type, he said that he had found the document in the street. Later he changed his story again, denying that he had ever seen the document.

The ritual was similar to that described in notes found 34 years earlier in the Sydney home of the murdered godfather Domenico Belle and in documents found in 1981 in the Canberra home of Domenic Nirta, who, along with five others, was charged over a cannabis crop in the nearby Brindabella Range. Convicted after a three-month trial in 1983, all six were later acquitted on appeal. In the late 1980s instructions for ’ndrangheta initiation rituals were found in the Adelaide homes of two suspected senior Calabrian mafia figures which had been raided by the police after surveillance of a mafia meeting.

These meetings were normally held each month. Venues were secret, with members being told only a day or two in advance. Guards were posted to ensure security. Among the issues discussed would be ‘family’ business, the collection of money and imposition of levies on local businesses, and the holding of ‘trials’.

Information about mafia meetings, membership and rituals revealed important facts about the structure of the organisation. John Cusack’s report had emphasised that the Calabrian mafia was not one ‘vast conspiracy’ but rather ‘a fraternity of criminals divided through its groups into any number of different criminal conspiracies. Members may belong to one or more such conspiracies which are often temporary in nature, organised to carry out one particular criminal venture’. Prophetically, Cusack warned: ‘If unchecked, the Society is capable of diversification into all facets of organised crime and legitimate business. This could very well include narcotics, organised gambling including the corruption of racing, football, etc, organised usury, and the large-scale receipt and distribution of stolen goods.’

In the mid 1960s, however, illicit drugs were not viewed as a threat by either state or federal police or by Customs. Nobody foresaw the looming drug explosion, or the rapid rise of the ’ndrangheta in the production and, within a few years, distribution of marijuana in Australia.

This is an extract from Evil Life by Clive Small and Tom Gilling, published by Allen & Unwin, $32.99. Available Now.