How Melbourne became a Calabrian mafia stronghold

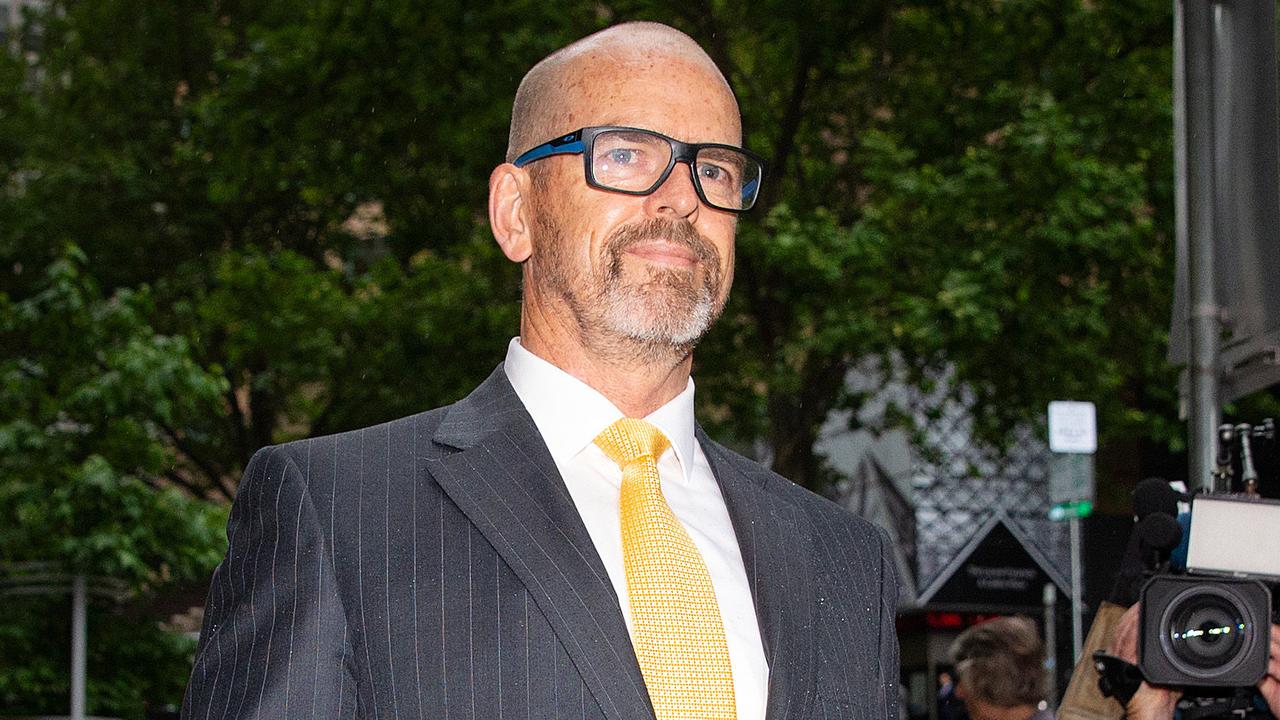

IF lawyer Joe Acquaro’s execution was a professional Calabrian mafia hit, it must have been for compelling reasons, because now the heat is on the whole business.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- GUNNED DOWN: Lawyer spoke of fears

- KNEW TOO MUCH: Lawyer knew mafia secrets

- LOVER: Girlfriend mourns family man with heart of gold

- RULE: Rumours rage over mob lawyer’s death

IT is almost always a last resort when the Calabrian mafia decides to commit murder.

That’s because it knows from bitter experience that doing so brings unwanted attention to its lucrative legal and illegal businesses.

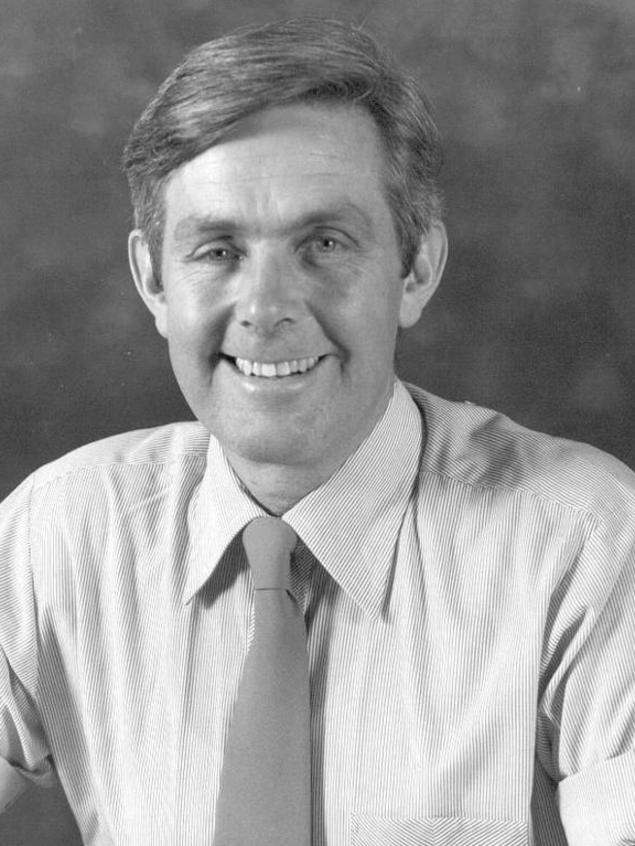

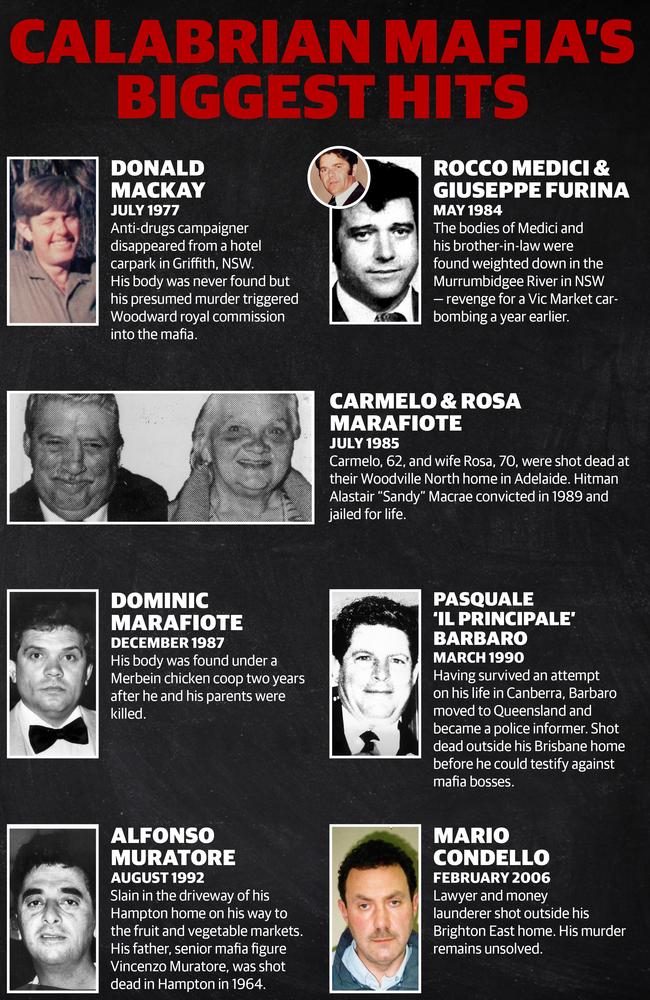

The Italian organised crime group learned its lesson following its 1977 decision to execute budding politician Donald Mackay in its stronghold of Griffith in NSW.

That resulted in the creation of the Woodward Royal Commission to probe the Mackay murder and the Calabrian mafia in general, and led to many senior mafia figures being named and shamed.

Australia’s first political assassination also prompted various law enforcement agencies to investigate what the Calabrian mafia was up to.

True mafioso — unlike some of the flashy, attention-seeking underworld figures who died during Melbourne’s gangland war — prefer to fly under the radar.

The unwelcome heat turned on them following the Mackay murder was bad for business and prompted a summit of godfathers from around Australia. That meeting decided they would never again commit such a high-profile murder — unless there were incredibly good reasons to do so.

Which is why if this week’s execution of Melbourne lawyer Joe Acquaro was a professional Calabrian mafia hit — and that is certainly the strongest line of inquiry — then it must have had compelling reasons to do so because, once again, police are raking over every aspect of its business.

It may be Acquaro was silenced for the same reason Mackay was executed — for being a thorn in the side of mafia godfathers.

Mackay because he told police about Calabrian mafia drug crops and the subsequent seizing of those crops cost the crime group many millions of dollars.

Acquaro because he was suspected of breaking the mafia’s “omerta” code of silence by speaking to the wrong people about its affairs.

Almost all Calabrian mafia murders in Australia since the 1960s have been committed either during internal power struggles; to punish members who broke the code of silence; to punish members who have brought shame on the organisation for such things as sleeping with another member’s wife; to prevent potential witnesses who might have testified against it in court; or to get rid of outsiders whose activities were seriously hampering its money-making enterprises.

Those include drug growing, importation and distribution on a massive scale; extortion of businesses; legal and illegal prostitution; and insurance fraud.

Calabria is in the toe of southern Italy and is the world HQ of the organised crime gang ‘Ndrangheta.

‘Ndrangheta is known by some Italians as L’Onorata Societa (the Honoured Society) or La Famiglia (The Family).

It is simply called the mafia by most in Australia, or the Calabrian mafia to differentiate it from the traditional Sicilian mafia.

‘Ndrangheta eclipsed the Sicilian mafia in the late 1990s to become the most powerful crime syndicate in Italy.

The Calabrian mafia has a tight clan structure. This often involves members marrying relations and sons taking over from ageing fathers to “keep it in the family” — which has made it difficult for law enforcement to penetrate.

The secret society has cells all over the world and has had a strong presence in Australia since at least the 1930s.

It is particularly prevalent in Melbourne, Mildura and Shepparton in Victoria, Griffith and Sydney in NSW, and Adelaide and Canberra.

The Calabrian mafia has been responsible for growing and distributing much of Australia’s marijuana for decades. It got involved in heroin importations in 1979, through now dead crime boss Robert Trimbole, and is known to have been involved in massive cocaine and ecstasy importations since at least 2000.

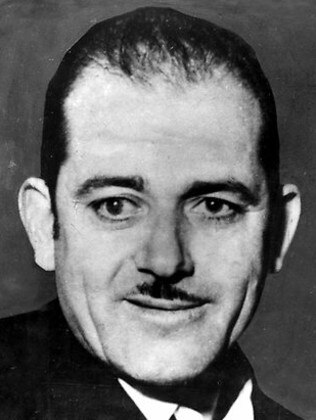

It first shot to widespread public attention in the 1960s as a result of a struggle for power within the Melbourne cell after the deaths by natural causes of Godfather Domenico “The Pope” Italiano and his enforcer, Antonio “The Toad” Barbara within weeks of each other.

Liborio Benvenuto emerged victorious and remained the undisputed leader of Melbourne’s Calabrian mafia cell for decades, but not before two mafioso died in what became known as the Market Murders.

Killed during that struggle for power were Vincenzo Angilletta in 1963 and Vincenzo Muratore in 1964.

Vincenzo’s son Alfonso Muratore was murdered in remarkably similar circumstances 28 years later.

Both Muratores died after being blasted by a shotgun as they left their Hampton homes in the early hours. Both worked in the Melbourne wholesale fruit and vegetable market and both were heavily embroiled in Calabrian mafia affairs.

The Muratore murders are still unsolved.

Benvenuto kept a lid on internal battles and largely stemmed what had been a flood of shootings, beatings and murders within the Calabrian mafia.

But he proved, five years before his death from natural causes in 1988, he was prepared to kill for reasons of revenge.

Benvenuto’s car was bombed at the Victoria Market in 1983 and he blamed prominent Calabrian mafia identity Rocco Medici for the attack.

He later arranged for Medici, 47, to be lured from Melbourne to Griffith on the pretence of organising a drug deal, with the intention of having him murdered as punishment for daring to bomb the godfather’s car.

Unexpectedly, Medici brought his brother-in-law, Giuseppe Furina, 41, with him on the drive to Griffith.

NSW police were provided with new leads in 2014 from a deathbed confession that strengthened the Benvenuto connection to the murders of Medici and Furina — including being given the name of the alleged hitman Benvenuto hired.

The information included that Benvenuto’s long-term bodyguard, Joe Rossi, was present when Medici and Furina were tortured and executed in what is still an unsolved double murder.

Detectives were told Rossi admitted to a friend before his 2008 death from cancer that Benvenuto ordered the Medici and Furina murders and that Rossi played a part in the payback executions.

They were also told in 2014 that Rossi rang Benvenuto from Griffith to alert him that Furina was with Medici. Rossi asked Benvenuto what the assassination team should do.

Benvenuto replied that Furina would also have to be disposed of because “he is in the wrong place at the wrong time”.

Medici’s ears were cut off and he was shot twice in the back of the head.

Injuries to Furina also indicated torture and he was shot once in the back of the head.

Both bodies were weighed down before being dumped in the Murrumbidgee River.

Detectives were told in 2014 that Rossi’s deathbed confession also involved naming the Melbourne-based Calabrian mafia hitman who allegedly murdered the men as Rossi watched.

That man is still alive and living in Melbourne as a prominent Calabrian mafia member. Police have not been able to get enough evidence to charge him.

A few years after the 1983 bomb attack, Benvenuto was diagnosed with cancer.

Knowing he was going to die, he sounded out a couple of people about taking over as godfather.

One of them was Alfonso Muratore — the same Alfonso Muratore who was murdered in 1992 — but they decided between them that Fonse was not quite ready for such a prestigious position.

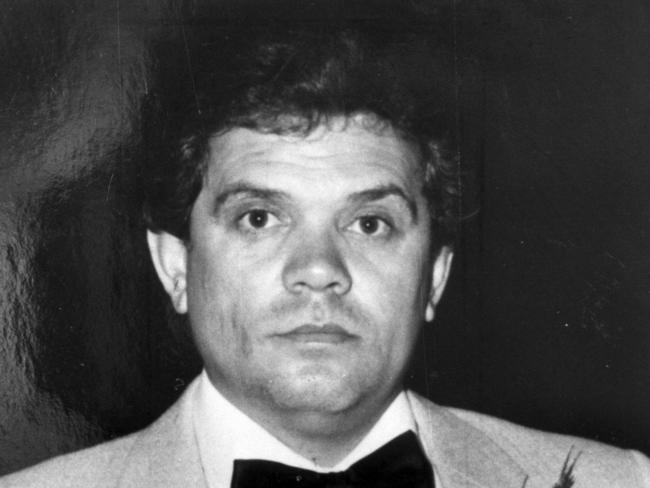

Next on Benvenuto’s succession planning list was Giuseppe “Joe” Arena, a senior Calabrian mafia member much valued in the organisation for his exceptional money-laundering skills.

Arena was also a feared member with a reputation for violence, a reputation no doubt boosted by the fact he was convicted in 1976 of murdering Modestino Spada and jailed for life.

He appealed and won a retrial and was acquitted of murder, but jailed for two years for manslaughter.

Victoria Police homicide squad detective Sol Solomon gave evidence that Arena killed Spada after finding him in a compromising position with a woman he shouldn’t have been with.

Although nominated as the next godfather by the dying Benvenuto, Arena never got to take on the top job as he was murdered by a rival faction six weeks after Benvenuto died.

It happened after Arena wheeled his rubbish bin to the nature strip outside his home in Bona Vista Rd, Bayswater, shortly after midnight on August 1, 1988.

Arena, 50, was killed by a single shotgun blast in the back — a traditional Calabrian mafia method of death with dishonour — as he walked up his driveway.

Police later found Arena had assets worth $950,000 at the time of his death, despite his claim he was simply a retired insurance salesman.

His death remains unsolved.

One of the few Calabrian mafia hits which have been solved was the triple execution of Mildura greengrocer Dominic Marafiote, 42, and his mother and father. He disappeared the same day as his parents Carmelo and Rosa were killed.

Carmelo Marafiote, 62, and wife Rosa, 70, were both shot dead at their Woodville North home in Adelaide on July 18, 1985.

The body of their son was found two years later. It had been buried under a chicken coop on a property at Merbein in Victoria.

There was speculation at the time that all three Marafiotes were murdered following a dispute over a drug deal and a falling-out with the syndicate involved.

But the Herald Sun can reveal police kept secret another equally strong motive for the triple murder.

Dominic Marafiote became an informer to police in South Australia in late 1982.

He gave them the names of Calabrian mafia bosses in SA, Victoria and NSW and also disclosed the location of a number of Calabrian mafia marijuana crops, subsequently seized.

A strong police theory is that the Calabrian mafia discovered Marafiote was informing and killed him and his parents as a warning to others not to do likewise.

Hitman Alastair “Sandy” Macrae was convicted in 1989 over the Marafiote murders and jailed for life.

It wasn’t the first time the Calabrian mafia had hired a non-Italian hitman to do its dirty work and draw attention away from it.

It paid Aussie painter and docker Jimmy Bazley to knock off Donald Mackay in 1977.

The long-time head of the Canberra cell, Pasquale “Il Principale” Barbaro did the unthinkable in 1989 — he became a police informer and began spilling the beans on the Calabrian mafia.

He did so after surviving an attempt by the Calabrian mafia to kill him while he was in bed with his younger Filipino wife Felisa.

He was hit by two shotgun blasts as he reached for his own weapon.

The injured Barbaro fled north in fear of his life and sought protection from Queensland Police.

He quickly named Calabrian mafia bosses in various states and rural centres in Australia, including Griffith, Melbourne, Mildura and Shepparton.

Realising the information he was providing went way beyond their jurisdiction, the Queensland cops passed Barbaro over to the National Crime Authority, which later became the Australian Crime Commission.

In a series of secretly taped interviews, Barbaro identified several Calabrian mafia bosses, named a number of its marijuana growers and dobbed in three senior figures who had forced more junior cell members to confess to crimes that could have seen the senior figures jailed.

The Herald Sun has seen hundreds of pages of transcripts of the secretly taped conversations between NCA officers and Barbaro.

In one, Barbaro said there were about 3000 Calabrian mafia members in Australia, but most were followers.

“You can destroy quickly when you send two, three dozen people out of the country,” Barbaro was recorded saying.

“New generation sick and tired. New generation want different life. When you send three, four dozen people out, no more mafia in Australia.”

Barbaro was also taped telling the NCA that a senior Calabrian mafia figure in Griffith wanted an associate, Angelo Licastro, murdered and arranged for a hitman in Calabria to do the job while Licastro was over there on holiday — a holiday arranged by the Griffith identity who ordered the hit.

The NCA contacted police in Italy and confirmed Licastro was murdered in 1982 while on holiday in the Calabrian mafia stronghold of Plati.

Licastro was questioned during the Woodward Royal Commission about his connections to marijuana crops in Griffith.

Unfortunately for the NCA, Barbaro was murdered before he could deliver all that he had promised — and before he could be persuaded to testify against the 28 Calabrian mafia bosses he named and linked to various crimes.

The NCA’s last taped interview with Barbaro was on January 23, 1990. He was shot dead outside his Brisbane home seven weeks later.

Police have no doubt Barbaro was murdered by the Calabrian mafia and have two motives for it.

The first is that he left his Italian wife for a young Filipino woman, bringing dishonour on his wife’s Calabrian mafia family.

In the warped and macho Calabrian mafia world, mistresses are allowed, encouraged even — but members are expected to always return home.

The second — and much stronger motive — is that the Calabrian mafia discovered Barbaro had broken its strictly enforced code of silence and needed to be silenced himself.

While NCA agent Geoffrey Bowen had no involvement with Barbaro’s interrogation, there is no doubt he was murdered by the Calabrian mafia because of his tenacious investigation into the organised crime gang’s powerful Adelaide cell.

The letter bomb which exploded in the NCA’s Adelaide office in 1994 killed Mr Bowen and severely injured NCA lawyer Peter Wallis.

Melbourne lawyer and Calabrian mafia money launderer Mario Condello was shot dead just after getting out of his car at his luxury Brighton East home in 2006.

There are several theories in the unsolved case as to why he was murdered. One of them is that he was executed on the orders of one of his own.

He was out on bail at the time, but had done time behind bars on remand after being charged over his plot to kill rival drug gang boss Carl Williams.

His Calabrian mafia associates knew Condello had struggled to cope while in jail and was dreading being convicted and having to go back inside.

The theory goes — and it is just one of several theories — that the Calabrian mafia feared Condello might decide to do a deal with police and turn informer rather than endure jail again.

Killing Condello meant his inside knowledge of mafia matters over decades went to the grave with him.

It is just possible this week’s slaying of fellow lawyer Joe Acquaro was done for similar reasons, to preserve Calabrian mafia secrets he was privy to.

That is certainly one of the motives the homicide squad will be examining.

But detectives will keep an open mind and go through every aspect of Acquaro’s life, including his financial dealings and personal and professional relationships with a wide range of people.

The prominent Calabrian mafia identities he represented and socialised with will be on the list of those they want to question.

CALABRIAN CONNECTION: Melbourne mafia’s market for murder

GIANT SHIPMENT: Mafia behind world’s biggest ecstasy bust in Melbourne

KEITH MOOR has been writing about Calabrian mafia activities for more than 30 years. Penguin is publishing Moor’s third book on the activities of the Italian organised crime gang in June. Busted will detail the history of the Calabrian mafia in Australia and reveal the inside story of the world’s biggest ecstasy haul — 4.4 tonnes of pills shipped from Italy to Melbourne by the Calabrian mafia.