Mafia wars and bodies: the colourful and bloody history of Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market

BODIES under the carpark. An explosion of bloody murders. The intervention of the FBI. Step inside the dark and brutal past of the Queen Victoria Market.

Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Melbourne . Followed categories will be added to My News.

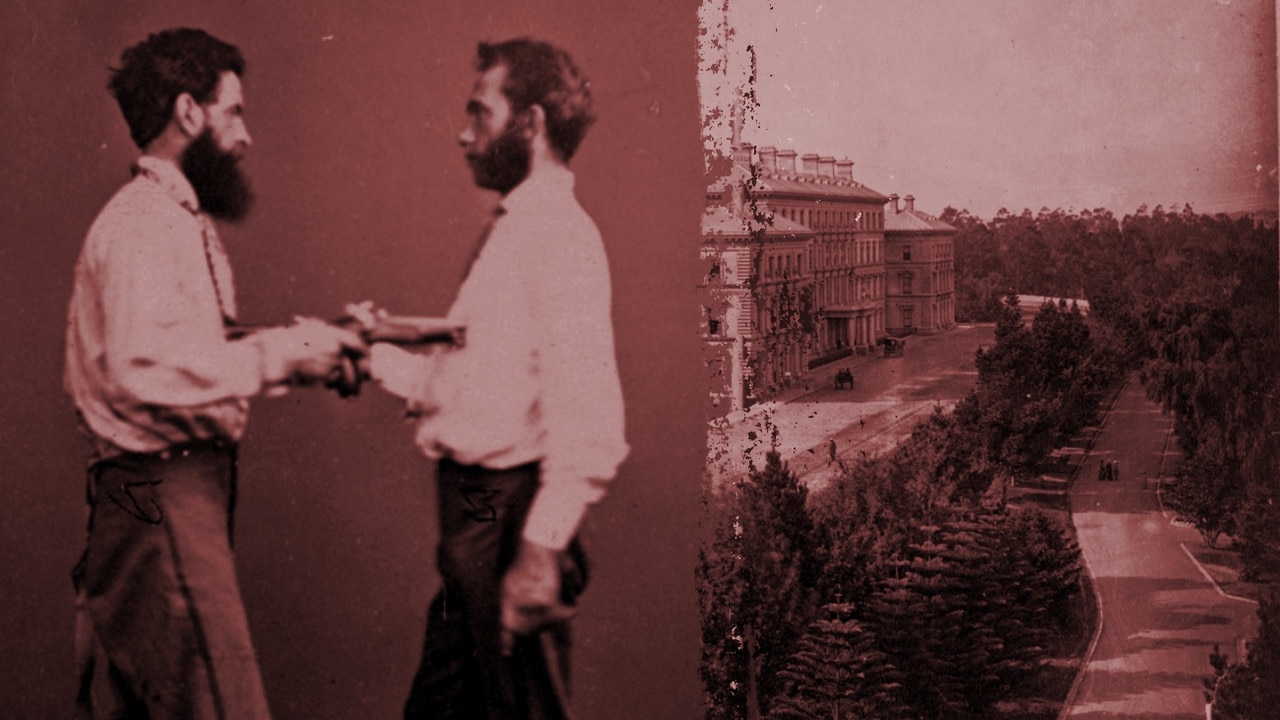

DRIPPING in history, Melbourne’s Queen Victoria Market has been one of the most significant meeting places in the city since it was first opened in 1878.

During its lifetime, the land on which the market sits has been a cemetery, a livestock market and a wholesale fruit and vegetable market.

The present day market started as a much smaller food market when it opened in 1878, before it expanded into the 17 acres it now occupies today — making it the largest open-air market in the Southern Hemisphere.

The city’s burgeoning population in the late 1800s led to a need to expand the market.

It was decided the best option was to extend the market over the Melbourne Cemetery, which operated between 1837 and 1854.

The oldest part of the market is the lower end we are familiar with — bounded by Elizabeth, Victoria, Queen and Therry Streets.

It was originally set aside in 1857 for a fruit and vegetable market but the location was unpopular and the market gardeners wouldn’t use it.

Instead, it was used as a livestock and hay market until it was permanently reserved as market space in 1867.

Nearly 1000 bodies were exhumed and reinterred to other cemeteries around the city during the extension of the market, including one of the founders of Melbourne, John Batman, who was later laid to rest in Fawkner Cemetery.

There are still about 9000 people buried under the market’s carpark today — but it’s likely they will never be identified after their timber headstones were stolen for firewood, and a fire in one of the wings of the Melbourne Town Hall destroyed all official records.

In 1929-30, the City of Melbourne constructed 60 brick stores on the current car park to house the wholesalers, but soon corruption and racketeering were rife.

A Royal Commission was launched in the 1960s to uncover the history of extortion, shady traders and violence — allegedly linked to the Calabrian mafia.

In the early 1960s, a struggle for power and control over the markets lead to a series of murders, stabbings and shootings that terrorised Melbourne.

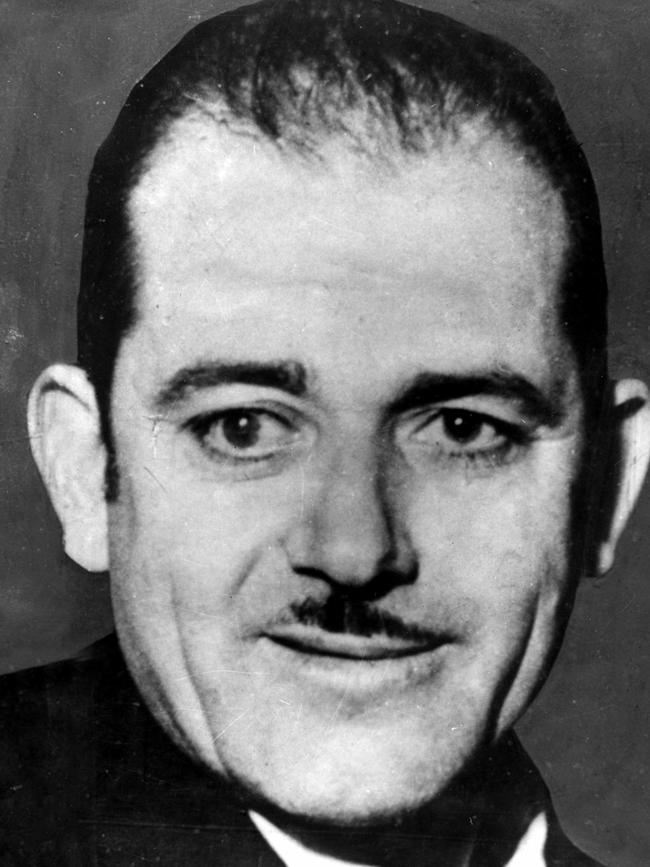

A bloody fight for leadership began when godfather Domenico ‘The Pope’ Italiano and his enforcer, Antonio ‘The Toad’ Babara, died of natural causes within weeks of each other.

The mafia fight for the top job spilt blood on the streets of Melbourne.

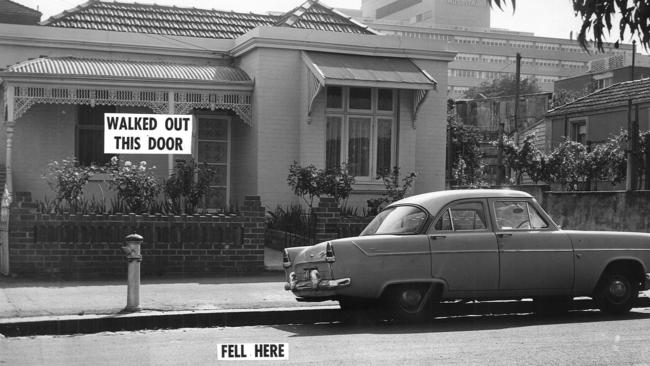

In 1963 fruit and vegie dealer Vincenzo Angilletta was executed by an assassin as he arrived at his Fairfield home after working at the market.

His death sparked at least two more killings and numerous shootings in what became known as the Market Murders.

Domenico Demarte and Vincenzo Muratore were blamed for the attack on Angilletta, and in November 1963 Demarte was badly injured by a shotgun blast in the back outside his Northcote home.

Then in 1964 Muratore was murdered by an assassin outside his Hampton home, and market identity Francesco De Masi disappeared in suspicious circumstances.

His blood-splattered car was found abandoned in a carpark.

No killer was ever caught.

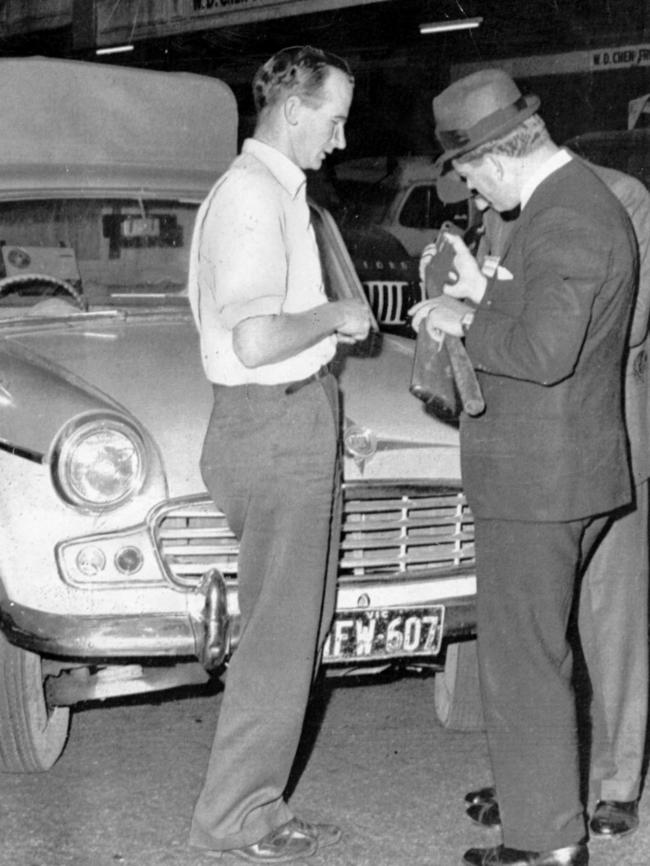

Under increasing pressure, Victoria Police called in the FBI from the United States to investigate.

FBI agent, John Cusack, helped unearth the activities of the secret criminal organisation and concluded there was a widespread criminal underbelly operating in Victoria.

The Royal Commission led to many changes in the fruit and vegetable markets, including the registration of merchants, limits on agents commissions, and the separation of retailers and wholesalers.

Vegetable growers and wholesalers were moved to the purpose-built wholesale market on Footscray Road in December 1969, separating them from the sellers.

The separation of the Wholesale Market from the Retail Market lead to plans in the 1970s to redevelop the market site into a trade centre, office and hotel complex, but there was a public outcry that resulted in the market being classified by the National Trust.