Nicola Gobbo always wanted the world to know who she was and what she was doing.

Her wider Catholic family claimed to have brought the first Italian espresso machine to Australia in the 1930s.

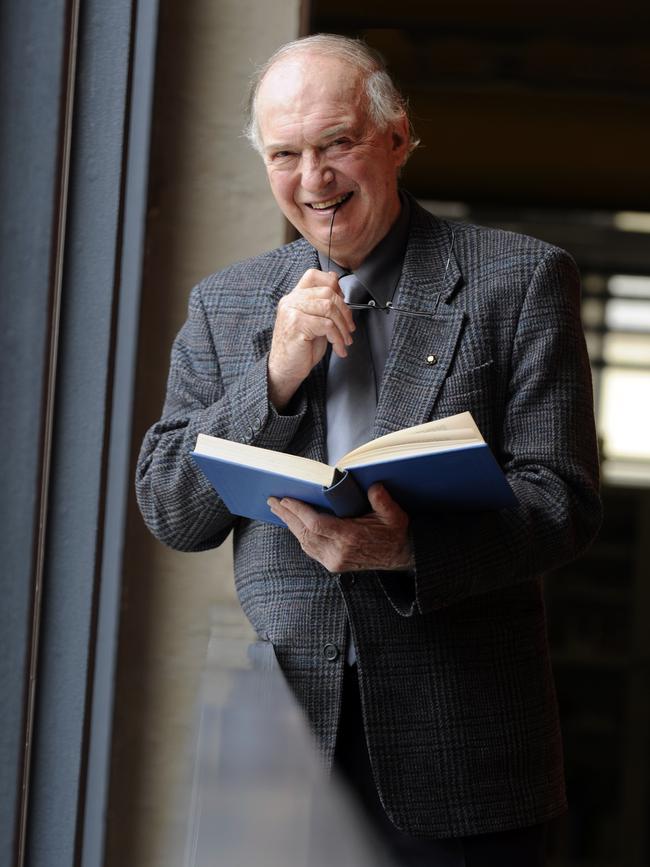

And did you know her uncle, Sir James Gobbo, was a Supreme Court judge?

She’d repeat this connection, constantly, in her early years.

“She was a show-off,” one of her University of Melbourne contemporaries says.

“She always wanted you to know that she was a Gobbo.”

The name-dropping trait traces back to her schooling at the exclusive Catholic girls’ school in Kew, Genezzano College.

Gobbo would relate to fellow students stories of her nightclubbing and her supposed sexual liaisons with door bouncers.

She spoke of encounters with Collingwood footballer Darren Millane, a wild child and regular at the Tunnel nightclub, who died while drink-driving home in 1991.

PART 3: THE MAN IN THE GOLDEN COFFIN

PART 8: HOW WE UNCOVERED THE TRUTH

Once, when another student alluded to Gobbo and Millane on a classroom blackboard, Gobbo rubbed it off — but looked pleased by the instant notoriety of her supposed association.

A prefect and house captain, she was “loud”, “funny” and “big”.

When her father died in the middle of year 12, fellow students attended the funeral.

Yet Gobbo never quite fitted in. She seemed to be trying too hard to impress.

“I don’t think she opened up to anyone about anything,” one fellow student says.

Gobbo presented then as she does now, in her non-lawyer guises: easy to like but hard to know.

Ask the beauty therapist who used to do Gobbo’s nails at late-night appointments, just down the road from the former homes of underworld families such as the Morans and the Williams. Gobbo liked to chat about her Bali trips.

She struck the therapist as “different and determined”, and in need of friends.

While studying law, Gobbo was the university’s newspaper co-editor.

Editing Farrago has currency as a stepping stone to journalism or political office and was a natural stop for a girl who wanted to be the first female prime minister.

Under a headline “The Place To Find A Well Hung Jury”, she wrote: “If the dancing frenzy and amount of alcohol consumed are any indication of future legal prowess, then those at the 1993 Law Ball will constitute an impressive addition to the profession.”

She seemed headed for fine things — like one peer, Peta Credlin, who would later be described as the nation’s most powerful woman, and another, former AFL honcho Adrian Anderson.

“She had this air that she was going to get a job at one of the top law firms in the state — Freehills, or something like that,” says one fellow uni student. “I was stunned a few years later to see that she was doing crime (criminal law). I remember thinking, ‘What’s happened there?’”

What happened was a drug bust in 1993, when Gobbo and her boyfriend were charged with drug trafficking.

She later pleaded guilty to use and possession.

She was first registered as a police informer in 1995, and many close observers link the two events.

She met the heaviest crooks when she worked with solicitor Alex Lewenberg in his criminal law practice in the late 1990s. She took calls from drug squad officers later convicted of corruption, and she gave information to internal investigators.

She would turn up late and loud to Lewenberg’s office, after careering through Richmond laneways to park her black sports car in a tight spot.

When Lewenberg gave her a pay rise, Gobbo celebrated with lunchtime vodkas. When she discovered the rise was only $10 a week, she confronted Lewenberg: “You can stick your f---ing pay rise up your f---ing arse.”

Lewenberg fretted that his employee was crossing lines.

She was too close to the crooks and — after he saw her being dropped off one morning to work by a man he thought was a police officer — too close to the cops, too.

She got to know Paul Dale, the detective later charged (but not convicted) over the 2004 killings of Terry and Christine Hodson. He would say that they had a sexual intimacy. He noted her short skirts and plunging necklines in labelling her “Amazonian”.

She shared traits with her one-time client, Carl Williams, who made hundreds of phone calls a day.

She pieced together puzzles and compartmentalised the pieces.

She was a puppet and a puppeteer — the “octopus”, as one of her handlers dubbed her, who knew more than anyone else.

Even her handlers were never sure which team she was on; after all, she was accepting money from the clients she was betraying.

Even her handlers were never sure which team she was on; after all, she was accepting money from the clients she was betraying.

She called her motives “altruistic”, though rumours swirl of her being pressed into police service when she was registered as an informer (number 3838) for the third time in 2005.

She would be set tasks by her police handlers.

Information reports seen by the Herald Sun do not depict an unwilling servant.

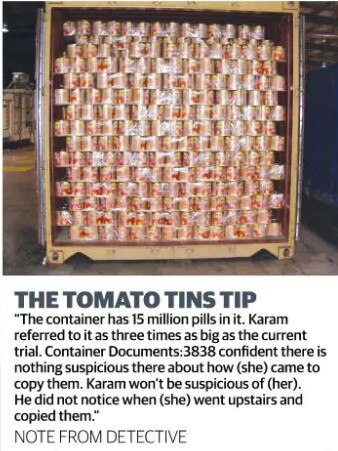

“3838 wants to know what (the source) can be tasked to do next,” reads one report relating to her duplicities regarding her client and convicted drug importer, Rob Karam.

There were late-night jail visits and bags of cash. There would be death threats and a car firebombing, and demands for $20 million from Victoria Police for, as she put it, “betraying” her despite her many years of “assistance”.

After a $2.9 million payout, Gobbo was still offering her services to police. But by 2014, the woman who had hosted gangland gatherings and snorted cocaine “with the boys” was seeking a suburban conventionality that was more in keeping with her privileged roots.

A fellow lawyer spotted her at Baby Bunting, in Bentleigh. Gobbo was heavily pregnant and trying to get her toddler out of the car, a smoke dangling from her mouth.

Though she was trying to blend in with everyone else, to be a fellow parent who volunteered more time and effort than most, the facade of normality was thin.

Gobbo was heavily pregnant and trying to get her toddler out of the car — with a smoke dangling from her mouth.

Her first child was said to have been conceived with a gay flight attendant, the second with Richard Barkho, a client who would be convicted of drug offences.

She missed one day of his court hearings because she was giving birth to his son.

So between kindergarten commitments, there were the family visits to maximum security prison.

“Say goodbye to Daddy,” she was overheard to say.

Her uncle, Sir James, is an exemplar of diligence and dignity, the figurehead of a family that, until now, has been steeped in good causes and decency. A founding member of the “Immigration Reform Group”, which wanted the White Australia policy abolished, he was appointed governor of Victoria in 1997. In 2000, the Bracks government declined to extend his term.

Sir James later spoke of his distaste at being a figure of controversy. He told the ABC in 2010: “There was a lot of stress, because nobody likes to open the paper and find yourself talked about. Even if some of it was favourable and some of it was unfavourable, you don’t like it.”

Sir James is now avoiding the uproar about his late brother’s daughter. He doesn’t know and he doesn’t want to know, is the message evident from a statement that asked for privacy.

His niece, the “black sheep”, has a different approach: she naturally basks in the spotlight. Throughout her fight to hide her double-dealing, and the threats to her life, Gobbo has clung to her famous name.

“For some reason her name, Gobbo, has some importance to her,” a very high-ranking Victoria Police officer says. “She refuses to drop it.”

Now the whole world knows who she is and what she has done.

Just as Nicola Gobbo hoped as a child.