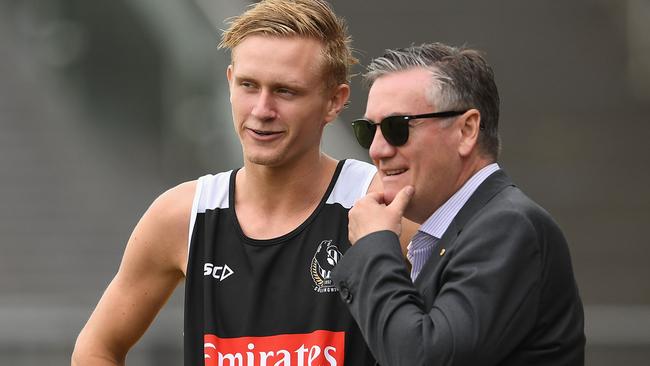

Eddie McGuire, the boy from Broady turned Eddie Everywhere

ONE of the most familiar faces on our screens grew up in Broadmeadows loving family, sport, news and his Collingwood Football Club heroes. Eddie McGuire has many names, various roles, endless energy and plenty of hats to wear, writes Hamish McLachlan.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

ONE of the most familiar faces on our screens is the son of an Irish mother and a Scottish father who migrated to Australia for new opportunities.

He grew up in Broadmeadows with a love of family, sport, news and his heroes who played for the Collingwood Football Club.

EDDIE ADMITS TO NERVES BEFORE FOOTY SHOW RETURN

MCGUIRE JOINS SUNDAY HERALD SUN AS GUEST SPORTS EDITOR

EDDIE MCGUIRE REVEALS THE SECRET BEHIND HIS SUDDEN WEIGHT LOSS

Fifty years later, not much has changed.

Edward Joseph McGuire AM. Ed. Eddie. Eddie Everywhere. Many names, various roles, endless energy and plenty of hats to wear.

We spoke about coal mining, sleepless nights, meeting Nelson Mandela, lucky breaks, dealing with dark times, what the Magpies premiership meant to him, advice to his younger self, and gaining perspective with age.

HM: Ed, you’re the son of migrant parents. What do you know about Bridie and Edward Sr’s lives as kids growing up?

EM: I know it was very tough for that generation. I think we take it for granted at times, all that we are so lucky to have.

HM: Your dad was a coal miner?

EM: When he was 12 years of age, he started in the coal mines. And then his career break was World War II, before coming out to Australia. Mum lived on a farm in Roscommon in Ireland, in a place called Boyle. It was almost Third World when you look back on it, but that was life in rural Ireland and that was life in the coalmines of Glasgow. They are very intelligent people, and they really made the most of the time they spent in school. They read extensively, and for them education was their passion and education for their kids was really what it was all about. As Dad says, when they felt the warmth on their back in Australia, they realised what an opportunity Australia presented for them and their family.

HM: What did they teach you?

EM: They gave us all a sense of optimism growing up. As opposed to looking back on hard times, they saw this as the step into the promised land.

HM: They landed in Port Melbourne in ’58 with two kids, two suitcases and five pounds, but they made a life.

EM: They did, and they moved into a cottage in Richmond with my mother’s brother for a period of time. Then they moved into my other uncle’s place, and within 12 months to the day of getting on the boat in Southampton they moved into their own home in Broadmeadows.

HM: Was that 74 Gerbert St?

EM: Yep, it’s still there. Our mum went in and showed a fair bit of determination at the Housing Commission to get a house, and in the end I think the guy relented and just said, “Look, it’s in a place called Broadmeadows. It’s not much of a place at this stage, it’s at the end of the line”. She said, “Don’t worry, we’ll take it”, and that was the beginning of it all. The Housing Commission gave them a house, and Mum and Dad gave us a home.

HM: It sounds like you had a very happy childhood?

EM: I did. I had a great community of people revolving largely around sport. At age five I fell in love with this new tribe that I became involved in called the Collingwood Football Club.

HM: Your dad was a Glasgow Celtic man?

EM: I became absolutely enthralled in the passion and love of sport through my father and his devotion to Celtic. I remember as a little boy, some of my earliest memories were in 1967 when Celtic won the European Cup. I remember holding Dad’s hand with a couple of his Scottish mates, and waiting for a film of the game to arrive. We then went to our place, put the sheet up on the wall, and watched the game over and over again as they drank more and more beer and whisky to celebrate the victory.

HM: They were different times. He was a boxing man too?

EM: My dad loved boxing as well, so we used to watch TV Ringside with the great Ron Casey and Merv Williams. I fell in love with a young bloke by the name of Lionel Rose, and Johnny Famechon — these two local heroes. I remember as a little boy lying on the floor at a barbecue on the day that Lionel Rose was fighting Alan Rudkin. Rudkin was an Englishmen, and most of the migrants were either English, Scottish or Irish, so at the start of the fight they were barracking for Rudkin, but apparently at some stage a little voice, which apparently was me, yelled out “Come on, Lionel!” They all looked at each other and realised, he’s right, we actually should be barracking for Lionel Rose! Thankfully, Lionel won. He was such a huge hero of mine as a young boy, as was Johnny Famechon. I just loved them.

HM: One of your idols growing up in your life was your older brother, Frank. He was a Bombers fan. How did you end up a Collingwood man?

EM: It’s still the greatest mystery to all of us! Growing up, Frank was everything to me. I literally tagged along behind him every step of the way. He is seven years older than me, and you couldn’t get a better big brother if you went to Central Casting! He looked after me, took me everywhere and taught me everything. At times he acted as a younger father, if you like, while Dad was an older father, doing everything he could, but going off to work at the same time. It was one of those things. In 1970, I was an impressionable five year old, and the Pies were having a good year, and I fell in love with Peter McKenna. Frank teased me a bit in the initial stages, never thinking I’d become a Collingwood supporter. I think Dad saw my love of the Pies in me. One day he took me to a Pies game and that was it! I remember the first I ever saw of McKenna was at the MCG in 1972. He kicked nine against Richmond. It was my first trip to the MCG, and I still remember it so clearly. From that early age, I just fell in love with the whole thing. The first time I went to Victoria Park it was game, set, match. I felt for the first time that I belonged somewhere. And since then, Collingwood has given me many great moments, not just at the footy, but it’s had a very spiritual and deep impact on my life.

HM: Frank didn’t get you into the Bombers, but he got you into journalism as a youngster?

EM: It was an interesting situation. I used to love watching the world heavyweight fights coming in from overseas. The Fraziers and Foremans, these sorts of fights. I remember sitting and just devouring the 1972 Munich Olympics. As a little boy I’d listen to the radio, and my mum telling me that I had to eat my eggs because Ron Clarke ate his eggs every day when he was breaking all the world records. Because Frank was so much into the sport, as well as my dad, that was a conversation around the place. On Sunday morning you wouldn’t breathe until the BBC had gone through all the results from England and Scotland in the soccer, so I had an international view of sport as well. For us as kids we didn’t go on any holidays, but we went to every sporting event that ever was, so that was our lives. I just fell in love with the whole sports aspect at such an early age, and the broadcasting. For me, our best family moments were spent sitting around on a Saturday night after going to a game, coming home and watching Football Inquest, and then watching then watching The Penthouse Club on Channel 7. People like Bill Collins and Mike Williamson were a big part of my life. They’d call the races and the footy on the Saturday afternoon, and then come and do a song and dance routine and host a variety show. Frank got into journalism straight out of school, so as a family we were all taking a crash course in journalism at that stage, following his career excitedly. When Frank became a journo, I was about 12 or 13, and he needed a stats man. He knew that I knew everything about footy. They didn’t ask how old I was, and luckily I’d shot up a little bit by that stage. I put a suit on and away I went!

HM: You used to duck into the rooms and get the latest on the injuries when everyone else was too afraid to go in there?

EM: I used the fact that people didn’t know who I was, and I was young and no threat. I’d get through the front door because I had a press pass, and then from there I was able to just wander around. Frank would file copy, and in those days you’d file it over the phone to a copytaker back at The Herald building. He’d do that, and I’d then sprint down to the rooms. Early on he told me which reporters to follow, which ones not to follow and how to get into the right spots in the rooms. I’d go into the medical room and get the injuries and then get the reports. They ended up keeping the paper open until I’d come up and file those reports, and then Frank would run down and get the interviews with the coaches before he came back and filed for the last edition. In the end you had those editions rolling off the presses, and it really taught me at an early age: 1) the speed and accuracy, and 2) what an amazing opportunity it was to learn how to file copy as a 13-year-old off the top of your head, and then buy the paper at the railway station on the way home to see if your own words were in there. Later on in life I have no doubt that it helped me with hosting, because it taught me how to actually think, get the quotes out, get the stories and give it all in one go, under pressure. As you know better than anyone, that’s what broadcasting’s all about. You get one go at it, particularly live broadcasting, and you’ve got to get it right. You’ve got to get the sense of occasion, you’ve got to get the accuracy right, and you want to get a little bit of poetry in there occasionally as well.

HM: What sort of a student were you? You a quick learner?

EM: I drifted in and out a little in relation to study. At primary school usually you had one or two kids that wanted the scholarship that you needed to win, and it went all right, but at a very early age I realised that my focus suddenly went to the media. I passed all my exams, passed my HSC and did all that sort of stuff, but it was more the other things I was doing on the weekend that I was concentrating on. To be perfectly honest, as a kid from Broadmeadows, you got out by being either a sportsman or a scholar. I was trying to hedge both ways at that stage. Sport was just such a big part of my life, and competing gave me a sense of worth, to go out and be able to have a kick or win a running race. I had some ripping teachers at several moments of my life where it could have gone either way in the sliding door moments. I had tremendous support at home, and a complete focus on “this is the way you have to go”. If there was one debt I would have to pay to my parents, my dad would say “Get into your books”, and that was Mum’s whole thing as well. She would teach me how to read, and Dad was very strong on the results side of things. I had some really great teachers at various stages where it could have gone either way, and they’d get me through to the next level. It also instilled in me a sense of wonder. For me, my real education was from the time I was basically five or six years of age. I read every paper, every word, everyday, and that’s really where I did the homework for my vocation later in life.

HM: Who got you into TV?

EM: I’d been sending out my applications everywhere, and I remember coming home from school on a Friday night and there were two letter, one from Seven, and one from Nine, saying “Thank you, we’ve got you on file, but don’t call us back”. Then another came from the ABC saying the same thing, and then I got one from Channel 10. As I opened it I was just thinking “here we go again”, but there was an invitation to come for an interview. In I went, and I remember waiting in the foyer, thinking “this is big-time”. A lady by the name of Margaret McHattie came out and said that I was to see the deputy director of news, David Johnston.

HM: How did you go?

EM: I sat down with DJ, and we hit it off. He was asking me all sorts of questions, and he had a great sense of humour, DJ. A couple of weeks later I came home from school on a Friday night, and the phone rang. I answered it, and it was David Johnston on the other end. He said, “We’d like you to come and start working on weekends”. I was at school doing HSC, and I remember that it just worked beautifully. He asked me if I could start the following weekend. It was the last round of the ’82 season, and I wasn’t going to be covering the finals for The Herald. I said that it worked beautifully, so I finished on Round 22 with The Herald, and started on the first week of finals in ’82 for Channel 10. This is my 41st year that I’ve held a VFL/AFL media pass. I just can’t believe my luck.

HM: In 1990 you were sitting on the ground as Leigh Matthews walked past with his arms in the air after breaking the drought.

EM: Well again, here’s another bit of serendipity. I got a phone call that week and was told that Robert Walls had booked an overseas holiday earlier in the year, and because there was a draw that year, he was going to be out of town. 3XY asked me to come and call the match, so not only did I do all the build-up for the Collingwood final, but the first VFL/AFL game I ever called other than the Battle of Britain game was the Collingwood premiership! How good is that!

HM: That’s unbelievable.

EM: And the deal was at the 15-minute mark of the last quarter I had to vacate the box, to go down and do my Channel 10 interviews. I went down and sat on the bench with Gubby and McAlistair and all the boys. What an amazing moment. The great thing about journalism that I’ve always loved — and the same goes for broadcasting — is that it gives you a front-row seat to history. I’ve been so lucky that as a young boy in this town I’ve been involved in so many amazing things that have happened.

HM: You seem to genuinely love this town.

HM: I do, and I think my love for Melbourne and Victoria is predicated on what it’s given me. I think our culture has come about because our major sporting infrastructure allows everybody to come in. You can turn up to anything, and it doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor; you can get in and enjoy it just as much. I still think Melbourne is the best place in the world to be poor, because you’ve got access to everything. It’s the land of opportunity.

HM: You talk about having a front-row seat to history. What’s the most significant moment, or broadcast, you’ve been involved in?

EM: Mine wasn’t even a broadcast, but it was a day I was hosting, where I was underneath the old trade centre in Melbourne, and a bloke walked in the door who was one of the speakers. It was Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. I was sitting there by myself, and in he came. I shake his hand and say hello, and we have a chat, and then the other door on the other side of the room opens up, and in walks Nelson Mandela. My mind just left the room, and I had this amazing out-of-body experience. Then I said, “Nelson Mandela, this is Rubin Hurricane Carter”.

HM: You introduced them?

EM: I introduced them to each other! It was the first time they’d met, and they were both speaking in Melbourne. I was standing there, almost like a referee, and Mandela shapes up in a boxing pose. Carter then shapes up, Mandela throws a punch, and they just embrace each other. I felt embarrassed being there, but absolutely privileged and understanding of what I was looking at. Carter then says to him, “Do you know my story?”, and Mandela says “Yes, I knew it. I knew it when I was in jail, and I followed it closely”. I still pinch myself. There was a photo taken at this thing, and I’ve been trying to find that photo for years. I’d love to have that photo.

HM: You’ve spoken about the significance of football. Nine and Seven circled when you were at 10, and Nine eventually got your signature. Ian Johnson was the mastermind of The Footy Show. Did you have any idea how The Footy Show would change your life?

EM: I had this real belief that it was going to be the show of its generation. No one else did, I don’t think! Johnno had a good feeling that it could be a good sports show, but no sports show had ever worked in prime time at that stage. I think it worked because it wasn’t really a sports show! But it did work, and it changed my life in a huge way. I remember Sam and I had famously met when I was 18, and we had a friendship and an acquaintance along the journey. I thought he was sensational, and I used to watch him on TV on a Sunday morning. Johnno sat me down and said to me: “Look, I’ve got an idea for someone to be on this show. Stick with me on this.” I just thought, “Oh no, who’s he going to throw up here”. He said “What do you think of Sam Newman?” I just had this absolute light bulb go off in my head, and I said, “I think Sam Newman is one of the most unique and funny blokes in the media”. He said, “Really, so do I. I reckon this will be great”. I threw up Trev Marmalade, who’d started off with me on radio, and we’d been long-time friends. We did one run through, as far as where the cameras would be. We didn’t ever do a pilot, and we didn’t do a practice run! Because my parents were a lot older than me, we had grown up watching the same type of British humour, like Johnny Carson’s show, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. We had a very similar background in live variety. Then of course we were watching Graham Kennedy, Bert Newton, Ernie Sigley, and all these types of people. It was all there, so when we walked out, what was interesting was that we both had the same idea of what the show would be, independently from each other. From the very first moment, it clicked for us.

HM: Somebody told me the first night you went out with Sam Newman you had $7 in your pocket. Probably not enough to go out with Sam, is it?

EM: Well, no, it wasn’t. I always say to the young reporters: “You’ll never get a story sitting in your lounge room. Always turn up, because you never know what’s going to happen.” There was this night when I was at Channel 10 in 1982. I’d been at the place for two weeks, and the extent of what I was doing at that stage was making coffee. They told me that there was a media night at VFL House. They said, “You drive past there on the way home, and drop in just in case there’s anything going on there”. So I turned up, as green as grass, naive to what was going on. I wasn’t even sure what it was or whether I’d even be allowed in! I walk upstairs, after arriving in my dad’s car and my brother’s suit, with my pocket money in my pocket, to buy lunch that day at Channel 10. The first person who grabs hold of me, and nearly breaks my hand, is Ted Whitten. Then I was introduced around the room as everybody turns up, to Ron Casey, Lou Richards, Jack Dyer, Bob Davis, Drew Morphett, Coco Roberts and Bruce Andrews, who played in four in a row for Collingwood. Ian Major and all the radio callers were there; Harry Beitzel. I’m looking around the room, and I realised …

HM: These were your heroes!

EM: It was the greatest moment of my life, and not only that, but they’re going around and they’re drinking long neck bottles of beer, telling war stories! I’m standing there just laughing my head off. They brought me into the circle as if I’d been one of their teammates for 25 years. Lou with all the banter, and Jack was just wonderful to me. It was amazing. At the end of the night, Drew Morphett said, “Son, would you like to join us for dinner?” I said, “Oh yeah, why not!” We go downstairs and Sam had a red Firebird or something like that, some sort of flash American car. We drove around to Toorak Rd, and I’d never been to Toorak Rd before. He realised straight away that I was a bit light on for money and Sam said, “Ed, I’ll be paying for this, I owe you from that golf game”, which we never played. He was very generous. He then took me across the road to Silvers Discotheque, and I got my first drink card. I watched him demand the DJ play that new one from Johnny Cougar, Jack and Diane. We became friends there and then. Who would’ve thought that 10 years later we’d be thrown together on Channel 9 at 9.30pm to do a show that would change our lives!

HM: Early on, you were known to roll out of a nightclub, roll down the hill, straight into the Bourke St studio and jump on the Richard Stubbs Breakfast Show. They were different times!

EM: I’d roll out of the nightclub, but three-quarters of the VFL was there with me!

HM: (laughs)

EM: And that’s what it was; it was good fun. We were all hanging around with each other, and we were good mates. We’d play tennis, and some Friday afternoon golf because we used to have Fridays off for working the weekends. It was enormous. That’s why I got to become friends with Dermott Brereton, but we were there under the tonne of the great Trevor Barker. Actors — like Peter O’Brien, who was the star of Neighbours in those days — would join us. Gary Sweet would come by, and we just had all these friends. Sam might come down occasionally. Trevor Barker would have it all organised, and again, these were just superheroes. Skyhooks were the biggest band in Australia, and Shirley was one of my idols. I was at 19 or 20 years of age, and two years earlier I was lining up to buy tickets for this guy. Suddenly I’m playing golf with them on a Friday afternoon and having a beer with them!

It was just amazing stuff, Hame. I pinched myself, and I always say to people, never lose the enthusiasm of life. Never become jaded. As soon as you become jaded about any of these things, it’s time to move on to something else. I’ve still got the twinkle and the wonderment in my eye, and I suppose that’s probably why, to this day, I keep pushing the envelope. It’s why I keep having a crack at different things, and keep enjoying it. I really draw from the energy. My wife, Carla, says to me all the time: “If you couldn’t retire, you couldn’t sit down, you couldn’t give up. That’s the life force that drives you”.

HM: Your workload is legendary — is it true that James Packer said in ’97 he was worried about you and you should slow down?

EM: (laughs) Exactly, yeah. I’ve got a few who’ve advised me about that, and I always used to say, “I’d rather hit the wall than die wondering where it was”.

HM: Have you ever hit the wall?

EM: A couple of times I probably should have pulled up a little bit. These days, while I’ve got a lot on, I am looking after myself a lot better, as far as not letting things get on top of me and affecting me as much as they used to. While you absolutely care and the desire to win is as great as it’s ever been, I’ve learnt along the journey that no matter how much I’m stressing, I can’t kick the goals for the Pies and I can’t coach the team or influence the rating. Only control what you can control, and don’t get wound up over what you can’t.

HM: Has family helped?

EM: Absolutely. Living my life with my boys and my wife means that I’m a lot more rounded, with a lot more perspective. That might be hard to believe, but I am more relaxed now than I was in the early days.

HM: What did you learn from Kerry Packer at Nine?

EM: I was always blow away by KP’s amazing general knowledge, and understanding of seeing things that other people didn’t see. He could join the dots on things so quickly. He was hard on himself and he might have been hard on others, but I thought he always had a soft side to him as well if he thought that you were having a go for him. I copped a few sprays along the journey, which I actually wore more as a badge of honour. I did have a good laugh once. We’d had a meeting about something, and Kerry put me in my place a bit on something. Later on, he said, “Son, I hope I wasn’t too hard on you earlier”. I said, “Kerry, my father lived in Glasgow, mate — that wasn’t even in the top 20!” I saw some very caring sides to Kerry, but I also saw a great loyalty, and if you were loyal to him and he knew that you were really fighting for his cause, then he backed you up forever.

HM: Collingwood. You were elected president in your last day of your 33rd year. Did you have any idea what you were getting yourself into, or what you needed to do to turn the club around?

EM: Nah, I didn’t. Not at all. If I knew, I mightn’t have taken it on! I actually started getting involved at Collingwood when I was trying to help Kevin Rose find some sponsors. Things were a bit crook there for a while. For the first 18 months I didn’t sleep. I’d wake up every morning at 3am, and I’d go into another room and write down all the things that were in my head. It would just consume me. It was very stressful. It probably wasn’t until Greg Swann came in as CEO that we worked out exactly how bad things were. I started to think that well, OK, now we know the depth of the problem, now we can start to rebuild. And then it became an amazing adventure.

HM: What’s the most difficult decision you’ve had to make in your role at the Pies?

EM: Probably leaving Victoria Park. That was a big roll of the dice! You get that wrong and you could destroy the club. It was at a stage where we were going all right, but I’d seen a lot of clubs struggling at that stage. I was breaking stories about Fitzroy and Footscray merging, and North Melbourne and Fitzroy, and ultimately Fitzroy and Brisbane. All of those things were going on; Melbourne and Hawthorn, two of the greatest clubs in football, they were about to merge. Clubs were going left right and centre, and to move from Victoria Park was a big deal. There were sleepless nights for a long, long time before that came to fruition. Ultimately we ended up getting to where I had in my mind, and that was to make Victoria Park our spiritual home for the U/18s, the VFL and the women. I wanted the Holden Centre to continue to be the No. 1 centre for elite sports training, and to continue with the MCG being the best stadium in the country, and to have the best facilities for our supporters and our players, so they could have the ultimate experience of AFL football. It all looks good now, but as we know, there’s a big leap of faith sometimes between the idea (and it) coming to life. There was a lot of deep breathing in that one, I can promise you!

HM: 2010. What did the premiership give you personally, emotionally?

EM: I looked back at the replay, and Leigh Matthews was interesting. He knew exactly what I was thinking at a moment when Chris Dawes punched the ball to Daisy Thomas, who then kicked the goal. I knew we were home at that stage, and it was the moment where he said, “Have a look at Eddie, he knows they’ve won but he can’t let it go just yet. He’s seen this happen too many times”. He was right. I started counting the players in case we had 19 on the ground! It was the only way we’d get beaten. It was one of those things that you still didn’t want to believe. It wasn’t until late in the last quarter with about five minutes to go that I started to celebrate. The cameras were all around me, but at one stage they all turned back to the game, and I was able to just reach my hand around the back of my two boys and give Carla a squeeze. She looked up, and I said, “We’re home”. She said, “Don’t say it, don’t say it!”. I said, “No, no. Boys, Carla, look around. This is going to be some of the most satisfying minutes of our lives”. The week before, we had the game stitched, basically, with five minutes to go in the second quarter, until St Kilda came back with a vengeance in the second half. When we went to the function after the first grand final, the feeling was that there was a curse on the club. I had to get everyone thinking that this was halftime, and we worked on it.

Mick Malthouse gave a great speech and the players lifted, and the disappointment and the exhaustion of the day lifted around us. When we turned up the next week, I just felt like we were going to win. We kicked the first goal, got on top and put the Saints away early. That was just a great moment, and for me, I thought about my parents, I thought about their journey, and I looked around the crowd and thought about all the stories that all these people had. For me, in those last five minutes I was thinking about my hero, Peter McKenna, the bloke who made me a Collingwood person. I knew he was going to finally have a premiership cup in his hands at the MCG. Then to go out onto the ground and see Peter hand that premiership cup off to Mick and Nick Maxwell, and to see the Collingwood crowd in the Collingwood social club, with the place rocking, was just phenomenal. Then to go across to the Holden Centre to the best post-celebration that had ever happened at that stage was just an amazing thing. It drew everything together, Hame. It drew the dreams of Collingwood, it drew the dreams of childhood, it brought together the heroes of my life and the people who have given so much to me. It pulled together all the threads of the presidency, of coming up with new ways of doing things, with the moving of Victoria Park and so on. It was an amazing moment of satisfaction and relief.

HM: You’ve been a huge part of delivering happiness to so many people. I can imagine it would have been extraordinary.

EM: It was great; it was just pure joy. It was all I hoped it would be.

HM: You’re not allowed to have favourite children, apparently. Do you have a favourite Collingwood player since you’ve been president?

EM: There’s so many of them. I love Tony Shaw for everything that he did for our club. He was a coach, and there’d never been a more selfless person at Collingwood than Tony. Players? Nathan Buckley has been a favourite for so many reasons. Bucks sometimes hates the idea that he made Collingwood big, because he’s such a humble man. I think at times Bucks would rather if he didn’t have any crowd at the footy, because it interferes with the actual pureness of the game. From my point of view, yes, it’s about winning, but it’s also about what the club means to so many people. Scott Burns was great, James Clement, Paul Licuria; what a game in 2002 in that first finals victory against Port Adelaide under my presidency! Then there are the heroes of 2010. Nick Maxwell is still so underrated, especially when you look at what he did in that first grand final. He dived and touched that ball on the line when Nick Riewoldt snapped towards goal. That was the bounce, bounce, bounce of the Jesaulenko goal that killed us in 1970. He got there. When Goddard took that mark, that was Jesa’s mark in 1970, but then he intercepted it and got us back in front. He did so many things that actually thwarted the horrific memories of premierships lost in the past. I know that Lenny Hayes won the Norm Smith medal that day, and people say it should have been him or Brendan Goddard, but there was a team that actually drew that day as well, and to me, there was no premiership, and there was no replay, without the skipper that day. Nick Maxwell’s just a ripper.

HM: Amongst all the success there’s been hurdles and challenges, and we all have ups and downs. Who do you turn to when things get dark?

EM: My wife, Carla, first, and then my closest friends and my family. I’m lucky. I have an elder sister who has always been great, and my brother, Frank, who is a very wise man. I know that he only has my best interests at heart. I’ve got a younger sister, Bridget, who has also been a tremendous source of support over the journey. I’m very lucky to have Carla, her parents and her family. Carla is not only my wife and not only my soulmate, but she is a constant source of inspiration and great wisdom. She’s a very wise person, and has a tremendous sense about her in that she sums up people and situations quickly. Sometimes I might start with a glass completely full, and she might be a little bit more concerned along the journey. She is the lioness of our family. She protects her three boys so much, and she’s there for us all the time.

HM: Does she sit you on your a--- when you need it?

EM: (laughs) Constantly! No doubt about that. They say life sometimes can be like your golf shot: starts up the middle and end ups in the trees, and sometimes you need to chip back on. Carla’s very good at saying right, OK, we need to have another look at where this is all going. At the same time, when I say, “No, no, this is where I think this is going and where I want it to go, and this is how I’m going to make it happen”, she’ll get right in behind me, 100 per cent. Luckily over the journey, we’ve both had a pretty good strike rate in getting it relatively right! Sometimes she’s right, and sometimes I’m right. It’s a great balance, and again, loyalty is a big part of everything that has worked in my life, and Carla’s loyalty and support of the family is just unbelievable at times.

HM: You know yourself very well. Describe Eddie McGuire in a sentence.

EM: Gee, I don’t know! People see snippets of me and see that as the whole person. I’d like to think there’s a little bit more to me at times, but ultimately, I’d like to say I’m an enthusiast and a progressive. I love the ethos of Collingwood, Melbourne, Victoria and Australia, and that is: “It’s not about where you come from, but rather what you do and what you put in that counts”. This is a very giving society if you’re prepared to give, and I’ve been very lucky that I’ve been the recipient of a lot of people giving me help, advice, guidance and love along the journey so far. If I can reciprocate that, then hopefully by the end of it all, it will be a life well lived.

HM: Last one. Advice to Eddie as a 12-year-old?

EM: Don’t be afraid, and have a go at everything. You won’t always succeed, but have a great time doing it all and work harder than the other bloke if you can. The motto I’ve always had from about that age was: If you’re not as good as your opponent, if you work hard you’re a chance. If you’re as good as your opponent and you work harder, then you give yourself a really good chance. If you’re better than your opponent and you work harder, then you’re going to give yourself every real chance of winning. There are no certainties in life, but when the invitation to life comes, be dressed and ready to go.

HM: Good advice for anyone — thanks, Ed.

EM: No worries, Hame. Good fun to look back at it all.