Andrew Forrest’s big challenge: convince Fortescue shareholders to go green

Andrew Forrest is a convert to a green energy future. Now he needs to convince investors who bought into his iron-ore vision.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If there’s one thing that’s raised the hackles of long-term Fortescue Metals Group investors it is the slick marketing campaign run by its green energy subsidiary.

As first revealed by The Australian last weekend, Fortescue Future Industries has its own private jet it quietly bought in May, which is used to ferry chief executive Julie Shuttleworth around the world. Stops in recent months include Britain, Canada, Argentina and Papua New Guinea – the jet has even been spotted on the Spanish island of Tenerife.

FFI has a rapidly growing headcount, and the Fortescue subsidiary – which has its own “global brand manager” – has run high-profile advertising campaigns around the globe, backing both the adoption of hydrogen as a fuel, and promoting FFI as the best way to get a piece of the action.

Fortescue founder Andrew Forrest has been front and centre of the campaign. In one video he appears at breakfast with a toast rack, berries and a newspaper, warning that “the party is over” for the fossil fuel industry. “Green hydrogen is the fuel of the future. I’m already in. You’re not going to let me take it all, are you?” he then asks.

There was also the painting of a fleet of London taxis green, ordering hydrogen-fuelled buses and Forrest’s attention-grabbing appearance at Glasgow’s COP26, where he dropped in on US President Joe Biden.

The stunts have heightened worries among some institutional investors who would prefer Fortescue stick to its metals and minerals businesses, and are concerned the hydrogen dream is a risky diversification for the company and a significant distraction from its money-making iron ore arm.

This week, Morgans analyst Adrian Prendergast wrote in a note to clients that “questions are emerging over how much focus [Fortescue] is placing on renewables versus its core iron ore business.

“The next five years in iron ore are likely to be more difficult than the last five years, warranting more focus or even possibly diversification into other mature markets. We … have lost conviction in the overarching strategy and capital framework.”

Yet despite the concerns, it appears the market is responding to FFI’s promise.

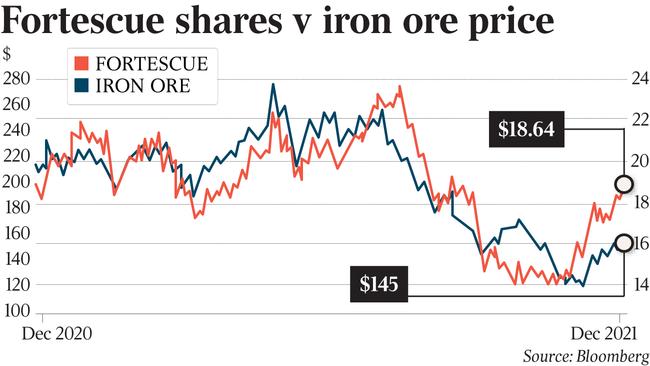

For most of Fortescue’s existence, the company’s share price has directly tracked the iron ore price.

Over the past few months that has changed.

Outgoing Fortescue chief executive Elizabeth Gaines told reporters last week she attributed the rise of FFI’s prominence within the company to its recent share price performance.

“If you track our share price over the last three, four years or longer, it will just match the benchmark. But more recently, in the last two to three months, we’ve seen that decoupling – we’ve actually outperformed the fall in the iron ore price and we outperform their peers,” she said.

FFI also appears to be changing the mix of investors on Fortescue’s register.

Forrest says Fortescue now has about 170,000 shareholders, double that of a year ago.

“There are strong tailwinds of support across the investment community and we are very grateful for it.”

While there will have been index funds that sold down their shareholdings when Fortescue was rising in value earlier this year, taking profits in the process, there does appear to have been something of a shift in the company’s list of shareholders.

An analysis of information gathered via Bloomberg shows several investment funds and exchange-traded funds with words such as “ethical”, “ESG” (environmental, social, and governance), “global sustainability” and “socially responsible” in their titles having bought in or topped up their Fortescue stakes or started tracking the stock this year.

One is the Vanguard Ethically Conscious Share ETF, which tracks ASX-listed stocks but “excludes companies with significant business activities involving fossil fuels, nuclear power, alcohol … and other controversies”. Fortescue is in its portfolio, nestled between the buy now, pay later company Afterpay and Sydney Airport.

Global investment houses such as UBS, Blackrock and Dimensional Fund Advisors hold or track Fortescue in similar funds or ETFs.

One UBS fund holds Fortescue via the MSCI World Climate Paris Aligned Index for investors wanting exposure to companies pursuing “opportunities arising from the transition to a lower carbon economy while aligning with the Paris Agreement requirements”.

Forrest says FFI’s global marketing push is a necessary part of its ambition to challenge global energy giants. He likens it to the time spent convincing China’s steel mills, in the early days of the company’s history, that Fortescue’s lower-grade iron ore products would have an important place in the market.

“When you’re going to create a new industry, you don’t create a new industry and then hope it’s just going to buy your product. That’s never gonna happen. You’re gonna go broke very quickly,” he tells The Australian.

“It’s not just marketing, because then you’ll have no credibility. It’s not just creating the industry, because then you’ll go broke because you’ve got no market. It’s not just persuading the workforce – because if you haven’t got both of those two, you’ve got nothing to employ them with. So you’ve got to do everything at once.”

And FFI is doing “everything at once”. Its teams are assessing hundreds of global renewable energy and hydrogen opportunities, trying to manage scoping and feasibility studies on a select few already subject to agreements with governments, and assessing and developing the technology needed to deliver the company’s ambitious hydrogen goals.

But Forrest bristles at any suggestion that FFI won’t be in a position to make the technology work in the near term, both at the required scale and in time for the company to meet its extraordinary goal of exporting at the rate of 15 million tonnes of hydrogen a year within a decade.

“We were able to convert the world’s first heavy truck to a green hydrogen fuel cell and have it operating within three months. Same with the (ammonia-fuelled) ship’s engine – proof of concept, done,” he said.

“Ship sailing on green ammonia, with no pollution for the first time in history – next year. Trucks operating at site – next year. Trains operating with no pollution for the first time ever – next year.”

FFI staff share that conviction.

When The Australian published a report on the weekend speaking of cultural problems within FFI, more than 200 FFI staff members put their names to an open letter to the reporters, criticising The Australian for telling “only one side of the story”.

“We proudly work hard, together as a team, in uncharted, challenging territory to create a new green economy. We do it because the world is overheating and we want to help save it for our kids, their kids and all future generations,” the letter said. “We are not chasing trillions, we are chasing an end to global warming the only way possible – sustainably. That’s what drives us.”

But doubts linger, both externally and within the company.

At its heart, the hydrogen production equation is relatively simple. It takes about 50kWh of electricity and 10kg of water to produce 1kg of hydrogen. The amount of renewable energy needed to power the electrolysers that convert water to hydrogen is also a factor – current University of NSW estimates suggest solar-powered hydrogen production would need 1.5GW to 2GW of renewable capacity to power a 1GW electrolyser.

That suggests the 250,000 tonne a year hydrogen production centre planned by FFI in Argentina, announced in November with a provisional cost of $US8.2bn, would need to build about 5GW of renewable energy generation capacity – or more than the entire capacity of WA’s South West Integrated System, which serves the Perth metropolitan region, including FFI’s headquarters.

While market and financial analysts say targets of getting hydrogen costs down to $US2 a kilogram by 2030 are achievable, many also argue that the mega-hydrogen projects currently in the planning stage are underestimating the capital costs.

Those costs are also a source of concern for Fortescue investors, despite assurances from the company it will not use its balance sheet to finance it.

In November analysis by The Australian of publicly available information and FFI announcements indicated that the cost of building just 13 projects identified by FFI as development candidates would be up to $US148.5bn ($195bn). Forrest says FFI is looking at hundreds more, with a view to winnowing the list down to the best 100.

He says he has held discussions with multiple lenders with “hundreds of billions” waiting for projects to become available, and argues that list is a substantial source of value to Fortescue investors, not a risk.

He says FFI will “create” the renewable energy projects, then sell them at a profit to infrastructure investors and fund managers after FFI has cut a deal to buy enough energy from the projects to produce the hydrogen. Customers are already lining up for offtake agreements. “I don’t need to own all these assets; I’m going to create them,” he said.

“There’s no way am I going to be an NL (company) in, say, Brazil, – who’ve given us a power purchase agreement, which is in the low $US20s. So we can do well out of that. Their cost of capital is 4 per cent for equity, and 1 per cent for debt. Who’s going to compete with that? It’s a sovereign utility.

“It gets the lowest possible capital and the shareholder doesn’t really expect much of a yield, so 4 per cent is fine. They get to keep the wind farm or the solar or the geothermal, and we get to keep the electricity and they’re delighted with that.

“This is why I’m so undaunted.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Andrew Forrest’s big challenge: convince Fortescue shareholders to go green