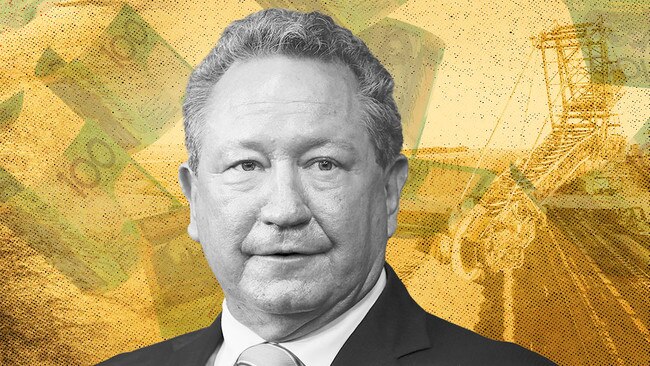

Andrew Forrest’s hunger for green trillions

Andrew Forrest is chasing a green energy dream, but insiders say his renewable energy business has become increasingly chaotic.

Andrew Forrest is chasing a green energy dream worth trillions of dollars.

But unfolding underneath the slick promises and huge investments at the mining billionaire’s Fortescue Future Industries is a corporate culture characterised as the “Hunger Games”, a work environment that can border on toxic and a company running with one objective: pleasing the chairman.

Fortescue Future Industries is Forrest’s most audacious move – a radical plan to transform global energy markets and turn the $50bn iron ore producer he founded, one of the big success stories of Australian business in the past two decades, into a renewables giant.

An investigation by The Weekend Australian can reveal insiders say the renewable energy business – a wholly owned subsidiary of Fortescue – has become increasingly chaotic amid ruthless internal competition.

Forrest, 60, admits the cold-blooded way FFI is sifting through hundreds of green hydrogen projects around the world has caused some friction. “Yes, I can see that people can misinterpret that as Hunger Games, but it’s not – it’s efficiency. It’s called strength of selection.”

He says he created a similar culture at Fortescue in its early days, when creativity was also the key to the company’s early progress – and was quick to note FMG culture had changed when operational excellence became the key to its ongoing success, saying the same would happen at FFI.

And FFI is quickly ballooning inside Fortescue. The company’s headcount has grown by 600 this year alone – a rate of three people per day. So too are serious concerns about the effect it is having on the wider business, which on Friday lost chief executive Elizabeth Gaines.

FFI now has more than 700 staff, its own private jet – a second-hand Bombardier Global 6000, bought in May for the use of chief executive Julie Shuttleworth – and conceptual agreements with dozens of governments around the world all funded by a promise it will receive 10 per cent of Fortescue’s annual iron ore profits; more than $1bn alone based on its 2021 financial results.

Such is the jostling and competition that staff who spoke to The Weekend Australian privately repeatedly described the company’s culture as being like the Hunger Games – based on the books and movies where groups fight to the death to win – with confused and conflicting reporting lines and big egos in middle management. Fortescue, like other companies, has a whistleblower hotline that allows staff to anonymously report concerns about corruption, bullying and corporate malfeasance. The Weekend Australian has been told of fears that even that has become weaponised amid the internal warring, with some staff expressing concern about alleged filing of false reports.

But other staff paint a far more positive picture of FFI’s internal workings, saying the “creative chaos” allows them to get on and make things happen without waiting for approval from senior managers, and empowers more junior staff to challenge ideas generated above their heads.

Boldest ambition

Billionaire Forrest, Fortescue’s non-executive chairman and biggest shareholder, has become increasingly hands-on in pursuit of his hydrogen dream.

“I’ve come into FFI on an almost full-time basis,” he says.

Forrest is so confident that he cites the world’s largest energy company as a marker of his ambition. “It (FFI’s plans) creates a Saudi Aramco scale, if not larger, company.” Saudi Aramco’s market capitalisation is $US7 trillion, making it the world’s second-biggest company behind Apple.

FFI is therefore the biggest and boldest play of Forrest’s career, one that has seen the one-time stockbroker and corporate failure turn Fortescue into a global iron ore force worth $50bn, build a $2bn investment portfolio that spans property, cattle and even the iconic RM Williams boot brand, and made him Australia’s biggest philanthropist.

Forrest is Fortescue’s non-executive chair and holds no direct roles on the board of any of its subsidiaries, according to filings with the corporate regulator.

But multiple sources said Forrest still wields direct influence over management decisions at FFI and sometimes even over Fortescue when they involve FFI projects – setting priorities, moving staff, and appointing external consultants.

“Now, I’m helping Julie. She’s the chief executive,” Forrest says. “But she’s got a chairman (in me) who’s fully committed and will nurse this company until he can step back – and he will step back. But until then, I will do everything in my power to make it successful.”

One former Fortescue manager, who still retains significant connections within the company, told The Weekend Australian there appeared to be “no accountability” within FFI for project delivery, only the need to maintain the approval of Fortescue’s biggest shareholder.

“Back when he was building Fortescue there was a group of senior executives – Peter Meurs, Paul Hallam and Steve Pearce – who were able to tell him to piss off when he started interfering,” the former manager, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said.

“Now he’s into everybody’s business, and nobody seems to be holding him back.”

Another former employee said the technical teams had been moved on from projects they had been running for months and reassigned “seemingly at a whim”, as new deals were signed and Forrest’s priorities changed. Forrest says a new organisational culture is needed to differentiate FFI as a “very fast-galloping herd” compared to Fortescue’s “orderly but very progressive and very goal-oriented” mentality.

“You do not get results and creativity from disciplined, predictable organisational structures. You get the greatest results and greatest creativity from a level of disorganisation,” he says. “(It is) where people generally know where they are going but they’ve got a very high level of freedom to go this way or that way. And they do, and they cross over into other people’s patches and it pisses them off. It seems ill-disciplined, but it’s not. It’s the opposite.”

‘Natural-born optimist’

Forrest has put few limits on the chase to become the biggest name in hydrogen. He contracted Covid-19 from a Russian interpreter in Uzbekistan, leaving him in a Swiss hospital. He was nearly the victim of a terrorist attack in Kabul. He shared a stage with Joe Biden in Glasgow.

While he can be a polarising figure, Forrest has plenty of backers who say he can make his dream come true. John Wylie, a prominent investment banker who has advised Fortescue on deals, says Forrest is “a natural-born optimist with a desire to prove himself, which is a refreshing contrast to most of the rest of corporate Australia”. Jack Cowin, a fellow billionaire who has investments alongside Forrest in a Canadian mining company, says: “(Forrest) is a 10 out of 10 for me. The sky’s the limit for him and more power to him for that.”

Forrest’s extraordinary vision and sheer force of personality have spurred those who work for him to achieve extraordinary things – building the Pilbara’s first new iron export infrastructure in decades to break down BHP and Rio Tinto’s dominance of the Australian industry is no mean feat.

But even Fortescue insiders are expressing growing fears his latest vision is spiralling out of control.

The Fortescue subsidiary has been adding staff so fast it has outgrown its first home – a single floor in an East Perth office block, around the corner from Fortescue’s headquarters. The rapid surge would create enough problems on its own, but current and former Fortescue staff point to Forrest as a significant additional cause of chaos at FFI. FFI staff are paid well compared to rivals but talk of long hours and even sleeping in the office, of being pressured to cancel leave and work through approved time off to achieve targets set by senior managers bent on winning Forrest’s approval.

New floors were rented in the same building to make additional space, but sources say that at one point the office was so crowded staff were working in shifts simply to have space to work in.

Make it happen

Those issues forced a major corporate reset at FFI in August, with Forrest launching a “freedom-driven culture” in a bid to break down silos within FFI, free up staff to take the time off they needed to gain the necessary creativity to pursue the hydrogen dream.

Employees were told they were now able to decide how they worked based on their “team’s productivity – your personal brilliance and your team’s brilliance”, according to staff documents.

FFI workers were told to ask themselves if they were acting in the best interests of the company – “this is not a hoax … not some gimmick”, a document said – and were told the group had to “work hard and fast to achieve great things others just talk about”.

There was also a lack of hierarchy across the business as it attempted to achieve “connectivity through the whole organisation”.

In an attempt to allay staff concerns Forrest has recently instituted a question-and-answer session with employees at FFI’s internal “green cafe” meeting spot. Staff submit questions anonymously and Forrest is not warned in advance about what they are asking.

“At the end of it you’ve answered honestly, everything. Sometimes it’s not good news but you’ve been truthful (then) harmony breaks out. I’ll probably have to do that a number of times until organisational philosophy really settles in,” Forrest says.

“But until that time, people have got to know that they can put the chairman on the mat anonymously, so they don’t fear at all and have their questions and their concerns addressed by him.”

Forrest disagrees with the wider Hunger Games analogy.

“People are stressed because there’s so much work (to do) in such little time. I haven’t noticed it – okay, maybe you would say that, Andrew, because you’re at the top – but the Hunger Games attitude where you’re always being reduced, reduced, reduced. That’s not the case.”

Unveiled by Forrest, who has an estimated wealth of $27bn, FFI has chased green energy projects that could cost up to $US650bn ($908bn) to $US1 trillion, according to some internal assessments, although Forrest disputes that figure. The deal-making spree is instructed by the acronym MIH – make it happen – a phrase Forrest once used as his email signature and is now incorporated into the name of at least one of his hydrogen subsidiaries.

In the past month FFI signed agreements with Papua New Guinea to develop up to seven hydropower projects and 11 geothermal energy projects, stitched up a contract that would see it become the largest supplier of green hydrogen to the UK and another deal to develop green hydrogen for the aviation sector in the US.

FFI is also conducting a suite of internal research projects into hydrogen production and distribution – including studies on the use of ammonia as a fuel for trucks, trains and ships, and the production of “green iron” from Fortescue’s Pilbara ore, using low-temperature electrolysis to produce a product that is 97 per cent pure.

‘Stretch targets’

Both the feasibility studies and scientific work, for the most part, have been the subject of Fortescue’s vaunted “stretch targets” – finding ways to achieve the seemingly impossible on shortened time frames and limited budgets. That stretch target culture has existed throughout Fortescue’s history, and is undoubtedly a significant contributor to the company’s success.

But Forrest says he and FFI management have also had to deliberately set out to make it different to the “old” Fortescue mining business. “With FFI … there’s a battalion that is probably 10 to 20 years younger (than Fortescue). You’re trying to tap their great intellect and their passion. You’re setting yourself up to be the most popular employer in Australia. You’re going to need the very best people this country has to offer.”

“And we knew that there was going to be a cost to that and a lot of older people would really struggle with it. And hardcore FMG people would either switch and go with it or struggle.”

This “freedom-driven culture” at FFI has also, according to sources, been used as a reason to pursue just about anything without due consideration of the real value the activity adds to the business.

Forrest defends the speed at which FFI is moving: “A lot of people get sick and tired of it all. Yeah, guilty as charged.” But keeping FFI forging ahead in the pursuit of his trillion-dollar dream is going to be a considerable challenge, even with his personal devotion and the backing of others.

On Monday: Building the Forrest empire.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout