Going green needs money, not charity: Andrew Forrest

The mining billionaire also has a $5bn investment and philanthropy empire. But when it comes to his green hydrogen dream, Forrest says it needs vast amounts of capital.

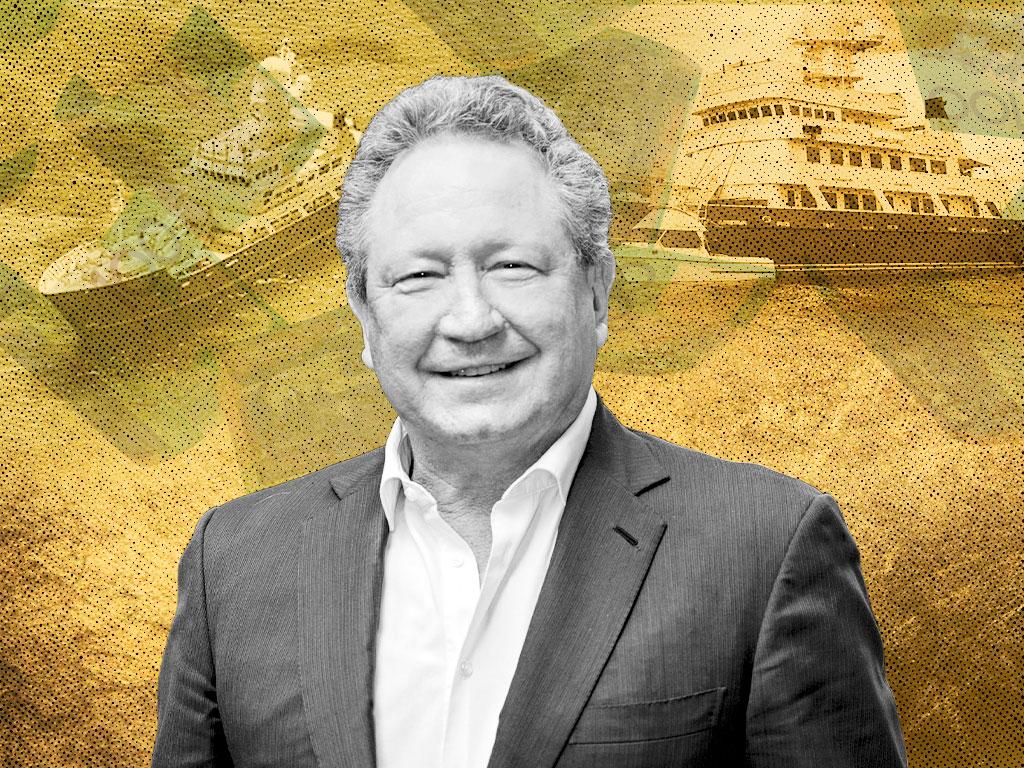

Andrew Forrest says there is only one way the world can deal with the challenge of global warming.

It’s money. And lots of it.

The billionaire mining magnate is adamant that when it comes to saving the planet, giving away billions of dollars won’t cut it – even if he is the most generous philanthropist in the country.

“The only force big enough in the world to do something about global warming is commerce,” the Fortescue Metals Group chair says in an extensive interview with The Australian.

Forrest says the forces of capitalism also need to be “supported by correct political regulation”.

“You can do so much with really directed energy and philanthropy, but you cannot do anything with global warming,” he says. “Philanthropy will not fix this. The only way you can ever solve global warming now is to make it commercial.”

So steadfast are his views that Forrest is stepping away from devoting what has been his considerable attention on his $5bn charity and private business empire to concentrate on his green hydrogen subsidiary Fortescue Future Industries.

Forrest has in recent years emerged as Australia’s most generous living philanthropist, donating about $2.6bn to his family’s charitable foundation.

He is also one of the country’s largest private asset owners with almost $2.4bn on the balance sheet of his Tattarang investment vehicle, an amount that has grown by almost $1bn in a year.

Both Forrest’s charity and investment choices stem from the 36 per cent stake he has in Fortescue Metals Group, which has funnelled $6bn his way in dividends alone in the past few years.

Those funds have allowed him to divert huge sums of money to charity – donating it to causes ranging from abolishing slavery to cutting plastic waste in the ocean, and also to go on a massive spending spree at Tattarang.

However, it is unlikely Forrest would have been able to do this – or devote so many resources to FFI – if it weren’t for a crucial meeting in a humble conference room in San Francisco’s Grand Hyatt hotel almost a decade ago.

While Fortescue is a $50bn giant today, back in September 2009 iron ore prices were crashing, Fortescue’s mines were not economical and Forrest and his management had started cutting staff as the company laboured under $10bn worth of debt.

In 2006, when Fortescue was a small miner looking for cash, it struck an agreement with the late New York fund manager Ian Cumming and his vehicle Leucadia for a $100m unsecured note that would pay a 4 per cent royalty when Fortescue’s mines went into production. (Leucadia also took a $400m equity stake that it later sold for a substantial profit.)

Fortescue’s production would boom and Cumming would call the note a “delicious investment”.

But by late 2012, Fortescue’s share price was plummeting, there were fears it would breach its debt covenants, and a legal battle with Leucadia loomed over the terms of the note. Forrest sent renowned investment banker John Wylie and the then Lazard Australia chair Paul Keating to negotiate a buyout with Cumming.

One meeting lasted minutes, ending when Cumming put his cowboy hat on, walked out the door and left Wylie and Keating with a free afternoon spent at Ronald Reagan’s presidential library.

At the next one, Wylie met Cumming for breakfast the morning after his niece’s San Francisco wedding, having travelled from Vancouver with Forrest’s warning to not come back if the price went above $400m ringing in his ears.

“Well, he agreed at $720m,” Wylie recalls. “I went back and Andrew said, ‘Fantastic deal, thanks, very good’. It was one of the great deals for Fortescue.”

The company’s share price has increased six-fold since.

Wylie says Forrest’s mentality is proof of what he calls Forrest’s “natural born optimism” and relentlessly pushing ahead with his plans. “You’ll be listening to the radio and it’s all gloom and doom on climate change and then Andrew calls up and it’s a jolt of high energy. This green-energy play could become the economic opportunity of our lifetime. That’s the guy.

“It has been very entrepreneurial of Andrew to maintain that shareholding. Others could have been forced to sell down their equity and lose control, but he didn’t. Full credit to him. It has allowed him to do what he does. He is like a classic American entrepreneur in that way.”

Now Forrest’s mind is focused on creating a new green economy via Fortescue’s fast-growing subsidiary FFI. He tells The Australian he believes he can make a bigger difference in the world with an FFI that by being the “Aussie Aramco” and challenging the Saudi giant to become the world’s biggest energy company.

“I’ve had to step away from philanthropy because I feel the conviction of my precious short period on this planet … is best served no longer as a philanthropist, but by getting FFI up and away,” the billionaire says about the fast-growing renewables division housed inside the ASX-listed iron Fortescue Metals Group.

“I’ve come into FFI on an almost full-time basis. So if I can make a contribution at all, to you, and your kids and the world, then it cannot be done through philanthropy. So I stepped out of philanthropy a great deal.”

Forrest and his wife Nicola’s Minderoo Foundation now has $2.6bn in net assets, putting it behind only the Paul Ramsay Foundation – named after the late healthcare billionaire who left his entire fortune to the foundation – in terms of the size of Australian charitable foundations.

Much of the income that has been injected into Minderoo has flowed from dividends Forrest has received from his iron ore giant Fortescue, of which FFI is a wholly owned subsidiary, over the past few years when the iron ore price has been running hot.

Forrest and his wife head a philanthropic effort that is helping to end slavery and cancer, funds Indigenous programs and supports other causes such as removing plastic from the ocean and fighting the rise of artificial intelligence and its threat to democracy.

Their Minderoo Foundation distributed about $110m this year – more than any other member of The List: Australia’s Richest 250 – and employs about 200 staff.

Minderoo board member Tony Grist says: “Andrew is busy with his business career, but he did set this up. (It is) a really ambitious and progressive foundation that has a businesslike approach with the impact it is trying to make and the things it is trying to fix.”

Forrest told The Australian he was used to moving seamlessly between being an mining leader, an environmentalist and a human rights campaigner, devoting himself to several causes at once.

“People would say, well how can you wear two hats at the same time? Well, you don’t switch. That’s never been my thinking. You do whatever it takes in one hat. You wear that hat,” he says.

But he stresses that when it comes to taking on global warming, a capitalism rather than altruism mentality is needed.

“There are still philanthropists having a crack at it and it’s all about research and promotion, but with commerce and wanting to do good in the world; the two are a confluence,” he says.

“We are not out there like some philanthropists saying everyone has got to go green hydrogen and people will say ‘Who cares, no one is doing it’. So that is why we have had to promote FFI.”

Forrest says he has “good people” leading both Minderoo and Tattarang, the latter of which has clinched a string of deals in the past year as Forrest expands on his business interests that mostly focus on Australian assets.

Tattarang is led by former NAB executive Andrew Hagger and chief investment officer John Hartman, who joined in 2012.

According to financial documents lodged with the corporate regulator last week, Tattarang made a net profit of $252m for the year to June 30, up from $105m in 2020. Those figures are based on dividends paid to Tattarang from investments, including Fortescue shares. Net assets increased by $965m during the year, reflecting an upwards valuation of the assets on the Tattarang balance sheet.

Tattarang owns businesses that collectively employ more than 2000 people, and Hagger says it acts as an “impact investment house” that “screens for commercial outcomes but also equally screens for environmental or positive job outcomes” when it is pursuing investments.

The most well-known asset in Forrest’s portfolio is the RM Williams boot-making brand bought for $190m in October last year, and his other holdings range from a string of mining and small-cap companies including a medicinal cannabis business and property such as a luxury Queensland Island, Byron Bay resort and West Australian caravan park.

RM Williams had revenue of about $150m and earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of $25m in 2020. Hagger says there has been double-digit growth of both since.

A note in Tattarang’s accounts says assets have fallen in value by more than $500m since June 30, which is likely based on the fall in Fortescue’s share price. But Forrest and his family still have a shareholding worth more than $18bn in the iron ore giant, which underpins his philanthropic and investment endeavours.

But with FFI growing rapidly, Forrest now wants Fortescue to be known for far more than simply mining iron ore – which is changing the very nature of the business and its shareholder base.

On Wednesday: How Forrest’s push for a green hydrogen is changing shareholder views about Fortescue Metals Group

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout