The secret meeting that kickstarted Twiggy’s hydrogen dream

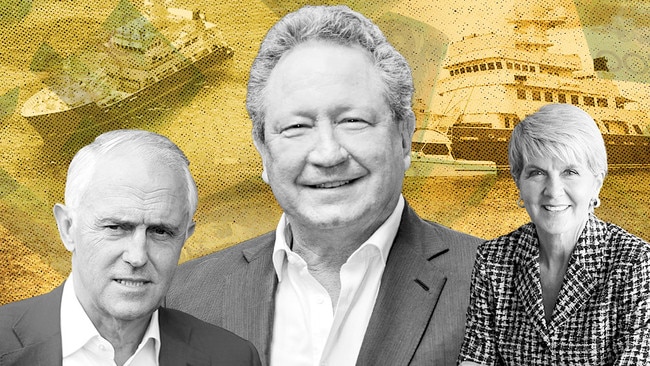

Andrew Forrest enlisted some of the biggest names in politics, business, science and security to turbocharge his green hydrogen dream.

Andrew Forrest needed a way to take his dream of turning Fortescue Metals Group from an iron ore miner into a hydrogen energy giant to the next level.

His vision was turning Fortescue Future Industries into a global player that would challenge even Saudi Aramco – the world’s largest energy company.

Forrest’s big move? Turning to a coterie of insiders, from a former prime minister to an ex-spy chief, for advice not only on the hydrogen technology but its implementation and expansion.

And it was in a luxury Margaret River resort – three hours’ drive from Perth – that they met in a secret February summit.

Forrest calls the meetings “think tanks”, and they have long been a part of Fortescue’s culture – meetings of executives, technical staff and board members, with a peppering of external experts to challenge ideas and thinking thrown up internally.

The hydrogen think tank was no different, Forrest says. And, although he had already announced plans to turn the company into a renewable energy giant, the meeting at the upscale Smith’s Beach Resort was a key trigger for the massive expansion of FFI this year.

Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, in February announced as chair of FFI in Australia, travelled to Western Australia for the meeting with wife Lucy. Another recruit, former Office of National Intelligence boss Nick Warner, was on hand to contribute the benefit of his three-decade diplomatic experience. So too was ex-foreign minister Julie Bishop.

Less eyebrow-raising was former chief scientist Alan Finkel, now a federal government adviser on low-emissions technology, who also dialled in to give his views on the technical and scientific presentations.

“I wanted external thinkers in to check our logic and check the board‘s logic the whole time,” Forrest says in an extensive interview with The Australian.

“It all came out of that, we knew we were going to have a real crack. And, you know, the unreasonable chairman said ‘look, I want to have a hydrogen fuel cell track and I want to see if we can do it in four months’.

“And then Lucy Turnbull said ‘well, if you‘re going to do that, imagine if you’re successful. You’d better have (intellectual property) lawyers with your engineers every step of the road because you’re going to need two teams now – you need a patent team, and you’re going to need a patent defence team’.”

The room sat for two days talking through the hydrogen plans, in what was undoubtedly a robust discussion, in parts.

And, while insiders worry the Fortescue chairman treats FFI as his own fiefdom, even his fiercest critics cannot deny he welcomes dissent – if anything, they say Forrest thrives on it when discussing ideas, even if he insists on the final say. One former employee told The Australian an understanding of how and when to disagree with Forrest is the key to surviving at Fortescue and the billionaire’s various private companies.

“The only way you can do the job is if you’re prepared to walk away at any moment,” they said. “He’ll come up to you and launch into the idea, completely tear it down. And if you’re not prepared to back it up on the spot and fight for it … that’s it, you’re done.”

But once Forrest has made a decision, the former employee says, that’s it – he expects everyone on board, and further dissent won’t be tolerated. Unless, of course, he changes his mind.

And before the Margaret River meeting had even happened, Forrest and Fortescue had committed heavily to the FFI idea.

Forrest, and a team of about 50 people from the company, had spent months in the air stitching up agreements in developing nations to develop.

Forrest has claimed Fortescue first started looking at hydrogen as a potential fuel source as far back as a decade ago.

‘Project ThoR’

At the centre of Forrest’s plans to turn Fortescue into a hydrogen giant is technology that does not yet exist at a commercial scale.

The uncertainty has led some Fortescue Future Industries insiders to describe the work as Project ThoR – the “Theranos of Renewables” – not because staff believe it is akin to the alleged fraud committed by the Silicon Valley healthcare darling, but because the enabling technology has yet to be completed. The market, and the company, is now valuing that idea far beyond its current ability to deliver returns.

But Forrest is certain.

Work on the green energy plan really began in earnest in late 2018, when the company acquired the rights to a “metal membrane” technology developed by the CSIRO that allows ammonia to be cheaply “cracked” into hydrogen, for use as a fuel.

Within months Fortescue had snapped up internationally renowned experts, led by former Engie Australia boss Michel Gantois and Bart Kolodziejczyk, and were getting serious about developing hydrogen fuel cells that could be used to power Fortescue’s fleet of Pilbara haul trucks.

But, as Fortescue’s new experts talked up hydrogen’s potential to decarbonise energy networks outside the company’s truck and bus fleet, Forrest got excited.

The company was already looking outside its traditional iron ore markets for growth, establishing exploration programs for copper and base metals in South America.

Forrest says he wasn’t that interested in diversifying Fortescue’s metals business into copper, lithium or nickel – the metals that will be needed for the world’s transition to low carbon energy networks. That is the same strategy pursued by Fortescue’s competitors. “Everyone says we should diversify, shareholders, employees, fellow leaders – everyone says diversify, diversify, diversify. But what I see is that every other mining company’s trying to diversify into iron ore – if they can,” he said.

“I kept the clamp down saying I don’t want to diversify for the sake of it. If there’s any industry which has a parallel with economics and with the ability to do good for the world that we see in iron ore, then yes.

“Only hydrogen, from the very early days, kept on coming up as one which would match or defeat iron ore from where it’s been as the number one pedestal for a resources company.”

Going his own way

At its heart the idea was simple.

Most of the easy pickings for hydro power, particularly those close to industrial zones or major mining areas, are already developed. In Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Europe.

So Fortescue would go where nobody else was operating, and build hydro-electric, solar and wind energy centres, and convert that energy into hydrogen that can be exported for a profit.

In the words of one former Fortescue executive, who left the company some years ago, it had the hallmarks of a “classic” Andrew Forrest idea.

“Andrew doesn’t like to follow the pack. If other people are doing it, he wants to do something better – in business, in philanthropy, everywhere,” he said.

“Andrew goes at an incredible rate – he has 50 ideas a day.

“And even if only one of them is any good, he’s the only person that could have had it.

“The problem comes when he wants everyone to work on all of them at the same time.”

When Forrest began his global hydrogen voyage in mid-2020, the team surrounding the project numbered 30 to 50 people – all bound to tight secrecy, even within Fortescue itself, through nondisclosure agreements. It is far cry from the at least 700 staff FFI has now.

Earlier on, though, the governments Forrest was seeking agreements with were asked to sign NDAs about specifics of the projects under discussion, though details quickly leaked out in many cases. Along the way FFI established operating bases in Croatia, and the Turks and Caicos Islands in the Caribbean, as it split into multiple teams to chase opportunities in Latin America, Africa, Europe and the US.

The early travelling team included Julie Shuttleworth, now FFI’s chief executive, key experts recruited in the early days of the hydrogen project, and long-term Forrest loyalists – including Michael Masterman, a go-to executive from Forrest’s early days as an entrepreneur.

Masterman was Forrest’s chief financial officer at Anaconda Nickel, played a role in Fortescue’s early days in iron ore, and rejoined the company in 2010 to negotiate the deal that would see the iron ore major join forces with Taiwanese steelmaker Formosa to build a giant new magnetite mine in the Pilbara. As the hydrogen push gathered pace, Masterman again joined up with Forrest, joining the boards of some of Forrest’s private energy companies, before becoming the FFI chief financial officer in October 2020.

Company tensions

In addition to negotiating with governments, sources say Masterman played a key role as a go-between with the traditional Fortescue business – smoothing concerns about the hydrogen push among operational leaders, and reporting back to Forrest about what was being said back at home base.

By early 2021 FFI’s direct staff had grown to about 100, sources say, after Forrest’s “big reveal” of his energy plans at the November 2020 annual shareholder meeting catapulted FFI into prominence within the company.

The mining magnate told shareholders at that meeting he wanted to make hydrogen the most traded global energy product in the world, replacing gas and coal as the world’s primary energy source, and for Fortescue to dominate that trade by producing 15 million tonnes annually by 2030.

To do so it would need to build about 235GW of renewable energy projects across the world – more than five times the size of Australia’s National Energy Market.

By the time the vision went public in November 2020, Fortescue had already signed early stage deals for the assessment of hydrogen and renewable energy projects in Papua New Guinea, Afghanistan, South Korea, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Iron Bridge blow

To study those projects, Forrest was raiding Fortescue’s own technical and engineering teams, exacerbating conflicts already emerging within its traditional business.

Sources say while key executives – including chief executive Elizabeth Gaines and finance boss Ian Wells, and operational leaders such as Greg Lilleyman – could see the benefits of the hydrogen and metal membrane technology to decarbonise Fortescue’s own operations, and then potentially as a platform to expand, they were less keen on the about-face in Fortescue’s business a global hydrogen push would require.

When it was announced in November, the hydrogen shift caught most of Fortescue’s workforce by surprise. Forrest, who presented the vision to Fortescue shareholders via video link from FFI’s base in Croatia, worked on the details until the last moment.

Only a small number of Fortescue’s Perth-based employees knew much about the sheer scale of the projects Forrest was gathering beneath the FFI wing.

But in January those underlying tensions between FMG and FFI came to a head, after The Australian revealed Fortescue’s Iron Bridge $US2.6bn magnetite project in the Pilbara was badly behind schedule and facing a large budget blowout.

Forrest is said to have been furious at the revelation – partly because of alleged “cultural” problems within the Iron Bridge team that had led to the concealment of problems, but also because The Australian’s reports undermined his arguments to the leaders of developing nations about Fortescue’s previous track record in delivering major infrastructure problems.

Within weeks the most senior managers responsible for the Iron Bridge had been cleaned out, as chief operating officer Lilleyman had fallen on his sword for allowing the problems to develop without his knowledge.

It was only a few weeks later – with that salient reminder of the consequences of failure at Fortescue in mind – that the Smith’s Beach meeting took place.

On Tuesday: Andrew Forrest, the businessman, his charities and his expanding investment empire. Read the first part of The Australian’s investigative series into the mining billionaire at theaustralian.com.au.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout