Australia's first kidnap for ransom: How Graeme Thorne murder changed Australia

FOR five long weeks the public watched and waited aghast for news after Australia's first ever kidnap for ransom. The terrible end to the case crushed a nation's innocence, but the breakthrough use of forensic science ensured police got their man.

IT was a terrible crime designed to take advantage of an ordinary family's good fortune in a more innocent time.

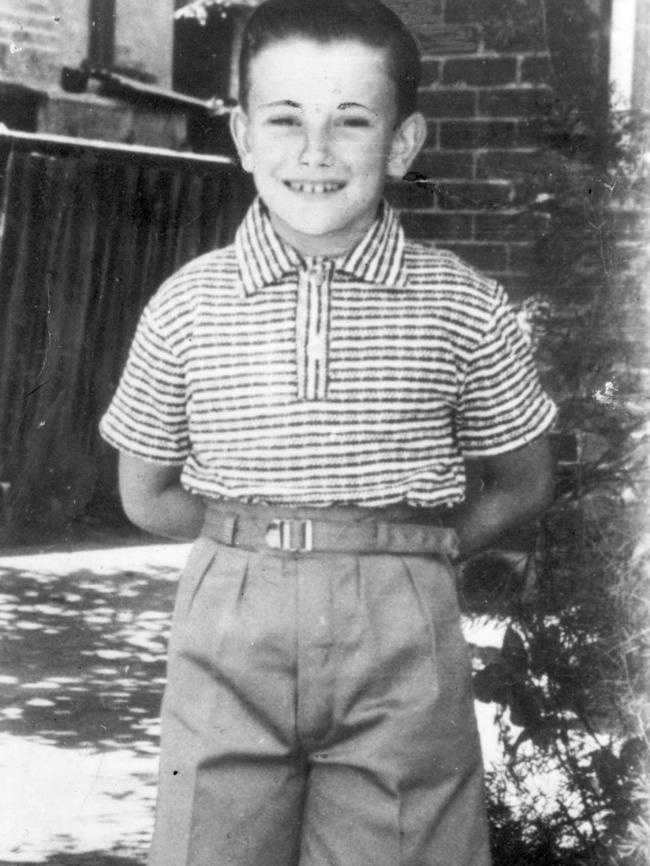

Fifty-eight years ago, Australia was rocked by the the nation's first kidnapping for ransom of an eight-year-old Bondi boy whose parents had recently won £100,000 in the 10th Opera House Lottery.

For five weeks, the shocked public waited and watched as police carried out an intense investigation to find little Graeme Thorne.

But the case was to have the worst possible ending when the boy’s body was finally found at Seaforth, on Sydney's northern beaches.

Black Widow's ex: Woman I loved shot me in the head

Australian Heist: 'We don't get paid enough to die'

On June 1, 1960, Graeme's parents, Bazil and Freda Thorne, won the lottery that was helping to build the Sydney Opera House.

In those days lottery winners became instant celebrities whose faces were splashed across the pages of newspapers and magazines, along with their addresses.

Kidnapping for ransom was seen as an American phenomenon, although France had experienced the kidnapping of a scion of the Peugeot family just three months earlier. But this was Australia and such things did not happen here.

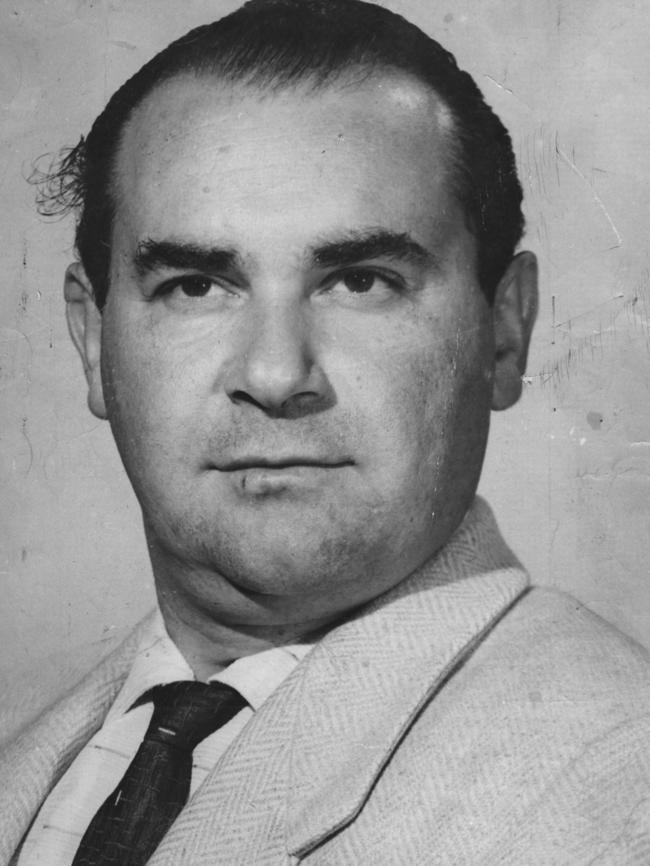

Enter Stephen Bradley, born Istvan Baranjay in Hungary in 1926, who arrived in Melbourne in 1950, anglicised his name and worked at various jobs.

Over the next 10 years, Bradley benefited financially from a series of suspicious events, including the death of his first wife and the destruction by fire of a guesthouse he owned at Katoomba in the Blue Mountains, but nothing was ever pinned on him.

By 1960 Bradley had remarried and was living in Sydney on the proceeds of the sale of his burnt but insured Katoomba guesthouse. But the Bradleys were living on their capital, so their funds were declining.

Inspired perhaps by the Peugeot kidnapping in France three months earlier, Bradley saw the solution to his financial problems in the person of young Graeme.

For more than a week, Bradley stalked the Thorne family, watching their movements and concocting his plan to kidnap their son.

Bradley struck at 8.30am on July 7, 1960, intercepting Graeme on his way to school and luring the boy into his car.

The police were quickly alerted and an officer was at the Thorne home to take the kidnapper’s call.

Thinking he was talking to Mr Thorne, Bradley said: “I have your boy. I want £25,000 before 5 o’clock this afternoon. I’m not fooling. If I don’t get the money before 5 o’clock, I’ll feed the boy to the sharks.”

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

Then began one of the biggest police operations in Australian history — one seen as the start of modern forensic investigation in this country — as a horrified nation looked on.

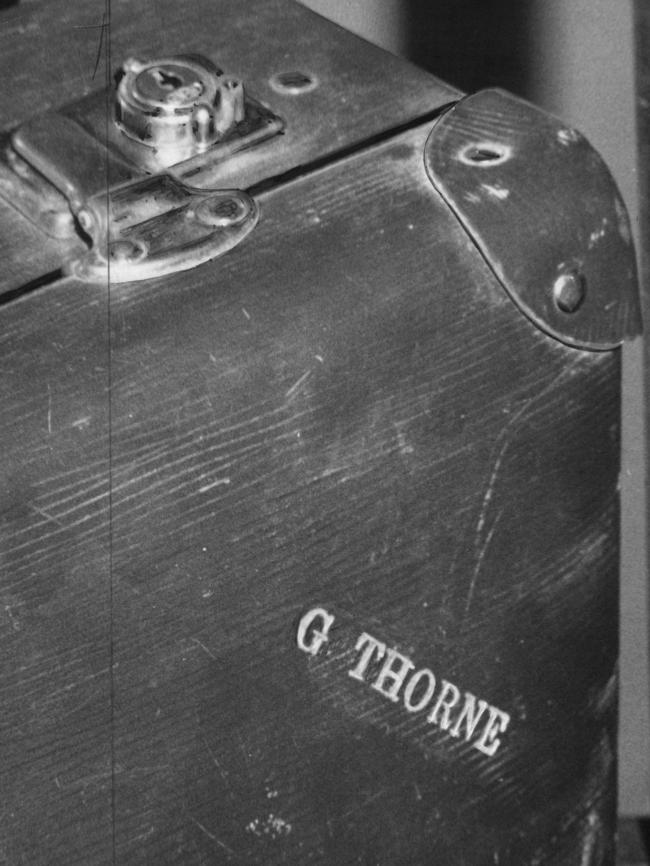

The first breakthrough came the day after the kidnapping when a walker found Graeme’s school case in bush beside Wakehurst Parkway at Seaforth.

Two days later, more of Graeme’s effects were found by police further along Wakehurst Parkway but they were no closer to finding Graeme or his kidnapper.

It was not until five weeks later — on August 16 — that Graeme’s body was found wedged beneath a rock on a vacant block of land in Grandview Grove at Seaforth. It was determined that Graeme Thorne had died of a fractured skull and asphyxiation.

The checked rug in which Graeme’s body was wrapped was to provide the police with the clues that would lead them to Graeme’s murderer, including twine, bottle-blonde human hair, hairs from a Pekingese dog, pink sand and leaf fragments from two species of cypress pine.

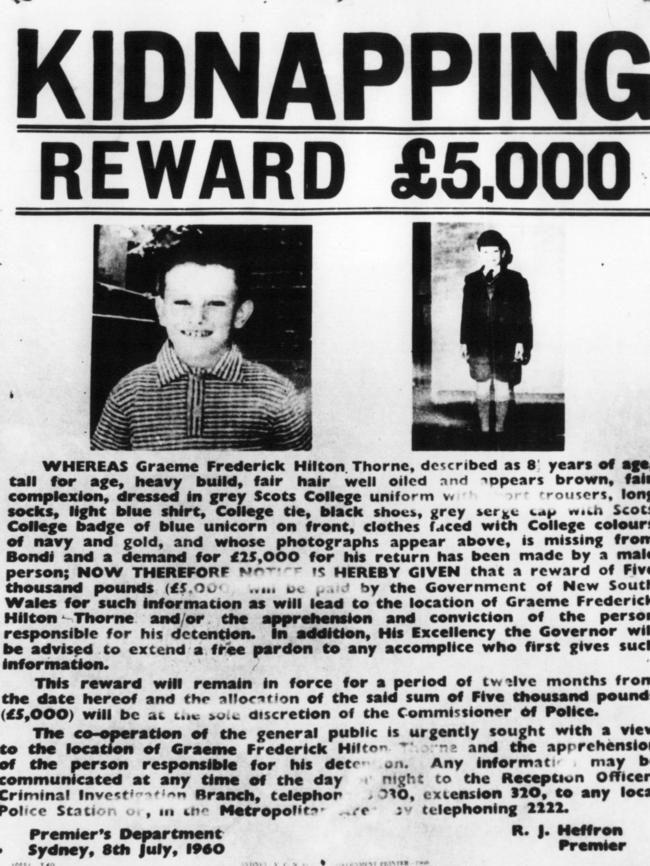

Police immediately scoured the Seaforth area on the premise the killer lived locally. A reward of £5000 was posted by the police and two newspapers offered a combined reward of £15,000.

The breakthrough came when a local postman and amateur botanist told police of a house in Moore St, Clontarf, that had pink mortar and the two species of cypress pine in the yard.

Police descended on the house but Bradley and his family had left, having sold the house and rented a flat in Osborne Rd, Manly.

At Osborne Rd, police again found the family had already left but they discovered more clues linking Bradley with the death of Graeme Thorne, including photos of Bradley’s wife sitting on a checked rug similar to that in which Graeme’s body had been wrapped.

The bottle-blonde hairs were found to belong to Bradley’s wife and the dog hairs from their Pekingese.

By the time the police were certain of Bradley’s guilt, he and his family were on the liner Himalaya, bound for England via Colombo, Sri Lanka. The master of the Himalaya was contacted and told to keep an eye on Bradley and, when the ship berthed at Colombo, Bradley was arrested.

After lengthy extradition proceedings in Colombo, Bradley was finally brought back to Sydney to face trial.

The weight of the forensic evidence was enough to convict him, and Bradley was sentenced to life imprisonment, despite many calls for the death penalty to be applied.

Having been found guilty of a crime against a child, Bradley suffered at the hands of his fellow prisoners in Goulburn jail, where he died of heart attack in October 1968, aged 42.

The Thornes, with their younger daughter, moved to another suburb but never really recovered, and Bazil Thorne died in 1978, aged just 56. Freda passed away in 2012.

It was one family's tragedy, but the the case had a far wider impact on the Australian way of life.

“It changed the way most Australian parents allowed their kids to play in public areas,” Mark Tedeschi QC, who wrote about the case in Kidnapped: The Crime That Shocked the Nation, told the Manly Daily in 2015.

“Before then, parents were very lax about letting kids play in bush and parks. Lots of people have told me it changed their childhood."

In separate interviews Mr Tedeschi also reflected on the forensic work that proved so important to solving the crime.

"This case really marked the beginning of modern-day forensic science in Australia — there were techniques that were used for the first time in that case that have since become quite commonplace," he said. "The resources that were thrown at the investigation were just enormous, both from the police point of view and the forensic science point of view."

The vacant land in Grandview Grove where Graeme Thorne’s body was found was sold by the Roads and Traffic Authority in 1994 and developed, obliterating the site of one of Australia’s most shocking crimes.

- This is an edited version of a story first published in June 2015