Eugowra gold robbery: The true story of Australia’s biggest heist

‘AHHH!’ screamed Senior Constable Moran, the third shot tearing into his testicle. ‘Jesus save me! My balls — he hit me in the bloody balls!’ It was 1862 and buckshot was flying in Australia’s biggest-ever gold heist.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT was one of the most extraordinary episodes in the nation’s history and remains our largest gold robbery of all time.

In 1862, a gang of bushrangers pulled off an incredible and bloody heist at Eugowra, just east of Forbes, NSW.

They escaped with a pile of cash and a staggering 77kg of gold — their total haul worth about $10 million today. But what happened to the gold?

True crime writer James Phelps tells the full story of Australia’s biggest-ever robbery for the first time in his riveting new book Australian Heist.

PROLOGUE

SOUTHERN COLORADO, 1903

THE old man turned his head, the simple movement a strain.

Frail and fading fast, he now found speaking an effort.

‘Get the boys,’ he said. ‘I need to tell them about the gold.’

Order issued, he closed his eyes, and his mind, mostly muddled these days, went to wondering.

Gold. Guns and gold. Australia.

He smiled, sunshine on a storm-ravaged face. He opened his eyes and looked towards the open window, the freshly cleaned curtains already collecting desert dirt.

‘King of the Road,’ he said. ‘You know that’s what they used to call me? Prince of Thieves …’

‘I’ve heard stories,’ said the elderly woman, moving towards his bed. ‘We all have. And I have no doubt they are all true.’ She leaned down and gave him a kiss. ‘I’ll go fetch the twins.’ He closed his eyes again.

Yep. King of the Road. Prince of Thieves. Australia’s greatest bushranger.

And again he smiled, for now this old man was young.

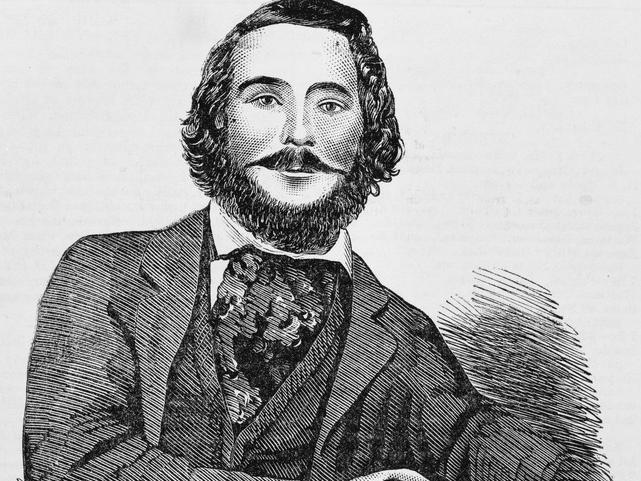

Frank ‘Darkie’ Gardiner was back in Forbes, no longer seventy-two, no longer on his Nevada deathbed. Frank was thirty-three, gun in hand, bum in saddle, galloping through gum trees after losing the law. On his way to drink beer at the sly shanty, bounty divided, bellies full. A hero’s welcome in wait.

A coughing fit brought him back to San Luis Valley.

A young man rushed into the room. ‘Dad, are you okay?’

He wasn’t. Gardiner hacked, heaved and spat. His throat smoked, his lungs burnt.

Gardiner’s son smacked him twice in the middle of his back.

The coughing continued.

‘What’s wrong with him?’ Lilburn looked to his mother.

‘You didn’t tell us he was sick.’

She didn’t have to answer.

‘It’s the old man’s friend,’ said Gardiner, gritted teeth and a gulp of hot air killing the cough. ‘He has come to take me home.’

At that moment Lilburn’s twin brother entered the cramped room. ‘Pneumonia?’ William asked. ‘The captain of death?’

Gardiner nodded before slumping back into his pillows.

‘Should have been a bullet, boy,’ he said. ‘I have been bloody blessed. Always thought it would be a bullet …’

Cough subdued, Gardiner summoned his strength. He grabbed William’s elbow, his hand a vice.

‘Boys,’ he said, looking first at William, then Lilburn. ‘You might have heard a thing or two about me over the years. You know what they would say back in San Francisco?’ His sons nodded.

‘Well, it’s true,’ he said. ‘All of it. And then there is more. Some of it, well, you might struggle to believe. But you have to. It’s my legacy and your future.’

And then Frank Gardiner, the King of the Road, Prince of Thieves, told his boys a tale of treasure. Of stagecoaches, shotguns and saddles. Of bandits called bushrangers, a bloke called Ben Hall, and a bounty that has never been beaten.

‘It was Australia’s biggest heist,’ he said. ‘Gold. Cash. Banknotes. And most of it was lost. Or so they say.’

And then he gave them a map.

THE ROBBERY

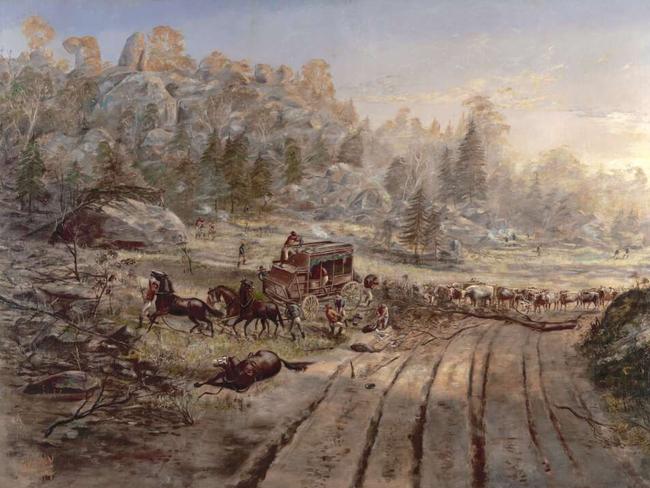

EUGOWRA, 15 JUNE 1862, 2.45PM

The trap stared at the scenery. It never changed. Pine-clad ridges lined a winding road of rough dirt. Grass fields, still green after a kind autumn and a warm and wet winter so far, touched the horizon. The fields were alive, endless and oblivious to the freeze that would come.

Constable William Haviland was fresh to the job, a trooper in the newly reorganised New South Wales police. He had a badge, a gun and a licence to shoot anyone who shot at him first.

He also had a sore arse.

‘How far to go?’ Haviland asked.

‘Ha,’ drawled Senior Constable Henry Moran. ‘Six hours. Well, unless a horse dies.’

Haviland, dressed in his newly issued uniform of blue tunic, waistcoat, kepi cap, cord pantaloons and knee-high riding boots, laughed.

‘That’s not a joke,’ said Moran. The senior constable stuck his head out of the stagecoach and pointed. ‘Have a look at these nags,’ he said, the four black horses heaving. ‘They look like racehorses to you? They are the cheapest nags in the goddamn colony. Look at that one. I think it has the plague.’

SNOWTOWN HORROR: ‘I DREAMT THE BODIES WERE COMING BACK TO LIFE’

WEEPING WOMAN: AUSTRALIA’S MOST BRAZEN ART ROBBERY

The weathered driver, a man called John Fegan, shouted down at them from his perch. ‘Would you two shut up? These bloody horses are smarter than the pair of you.’

‘Pipe down, old man,’ Haviland said, ‘or you might have yourself an accident.’

Sergeant Condell, riding shotgun, intervened. ‘Oh would all of you just shut up,’ said the boss as he slammed the butt of his tengauge Remington shotgun into the floor of the Ford & Co. coach.

Fegan flinched, expecting a blast. ‘F---ing watch it with that thing,’ he said. ‘That would kill a bloody elephant.’

The sergeant pointed the eighteen-inch barrel at the driver’s face. ‘Just f---ing get us there. Let’s go.’

FOLLOW: TRUE CRIME AUSTRALIA ON FACEBOOK AND TWITTER

Fegan cracked his whip and the horses jumped ahead, the metal-rimmed wooden wheels hitting rock. The Ford & Co. jolted, rattled and nearly rolled. The force was not dulled by the wagon’s state-of-the-art suspension. Back in the cabin, Haviland’s shoulder was sent smacking into steel.

‘Ahh!’ he cried, as his deltoid rammed a metal box. ‘Jeez, that hurt. What’s in that thing — lead?’

Moran shook his head. ‘Gold, you idiot,’ he said. ‘You think we would be guarding lead?’

The four boxes of gold were being transported from Forbes to Orange under the command of Sergeant Condell.

That morning, pistols drawn, the constables had watched on as Chinese workers had filled the wagon with riches, Fegan smoking nearby. By the time Condell arrived, elephant gun and all, they had put 170 pounds of gold in the wagon, most belonging to the Oriental Bank and the rest to prospectors and other banks. There was also cash — 3,700 pounds in all.

It was a fortune, but the officers were oblivious to the load and to the threat. They were flat-out bored. Around them was nothing but green grass and ghost gums, though an early swooping magpie gave Fegan a fright.

‘Oh, shoot that winged wretch,’ he cried, the driver looking towards Condell’s behemoth blasting gun. ‘It’s not even spring, it doesn’t even have any young to protect yet. It is just after blood. A flying demon.’

They had been on the road for about four hours when the man with the big gun saw something he didn’t like.

‘What’s up there?’ Condell asked. ‘Can you see that?’

Fegan nodded, his eyes squinting against the afternoon glare. ‘Mmm,’ he said. ‘Cattle?’ He applied pressure to the rein and the horses slowed.

‘It’s a bullock team,’ the sergeant said. ‘They’ve come a cropper. Keep on moving.’

The coach pressed on, the bending trail slowly revealing the rest of the road. Ahead, in the winding rough, bulls grazed, their bullock carts all busted and broken. Hay, at least a ton, baled by stringed bark, had spewed onto the trail. The biggest bull was pushing its snout into a pile of pulverised potatoes.

The driver shrugged. ‘Righto,’ he said, ‘we will have to go over there. The only way around is by that big rock.’

HALL JAMMED THE FRESHLY OILED TEAK INTO HIS SHOULDER.

BREATHE …

He gulped, a short hard suck sending frost into his lungs.

The frigid air, stained by wet eucalyptus and green grass, forced him to grab at his chest. Heart attack? No. Panic attack? Oh s--- …

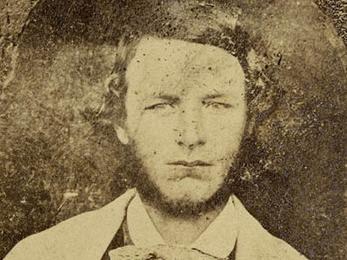

Australia’s newest outlaw issued himself an order. Pull yourself together.

Hall dragged his left hand from his heart and pulled his fingers into a fist. He watched as the red rushed away, his knuckles turning white. His hand shook.

Again he spoke to himself. This is the only way to get it all back.

He leaned his head to the right and his cheek hit steel. The barrel of his double-barrelled percussion shotgun was frozen, the weakened winter sun bouncing off the machined metal. He was no longer shaking.

‘Soon,’ cautioned Gardiner, squatting behind the sunscorched rock. ‘Not long now.’

Face blackened, everything but his eyes covered by a red scarf, Hall looked down the length of his gun, closing his left eye and focusing his right. Loaded with gunpowder and metal balls, the gun was locked, loaded and ready to kill. Soon he would be a finger-pull away from delivering death.

This is the only way to get them back.

He stood behind the rock with Gardiner, O’Meally and Fordyce, all disguised by red scarves and black polish. They were silent, but the crickets chirped, the birds tweeted and the falling foliage rustled.

‘Shhh,’ Gardiner said, more directed at crickets than his already silent men. ‘Nobody say a word. Here they come. Fordyce, straighten up.’

Gardiner studied his mark and then nodded. ‘Now!’ came the cry, Gardiner launching from behind the boulder to confront the coach, aiming the shotgun up into the air.

Bang!

The blast silenced the crickets.

‘Bail up!’ Gardiner cried through drifting gun smoke. ‘This is a stick-up. Stand and put your guns down. No one has to get hurt.’

The driver stuck his hands up before diving for cover.

‘Don’t shoot,’ he cried.

But another man, dressed in police-issue black and blue, took aim.

Bang!

The earth shook like a cannonball had struck, the force of the blast sending the trap in the coach crashing back into the leather upholstery that lined the seat.

Hall peered out from his hiding place then instantly ducked.

The buckshot smashed only rock, pieces of the boulder turned into splayed sand.

Then Ben Hall pulled the trigger and officially became a bushranger.

Crack! He fired off his first shot, his shotgun spewing steel.

Boom!

Like lightning, he flicked out his powder flask and filled his barrel with powder. Next he shoved in balls.

Bang!

Again.

MORE FROM JAMES PHELPS

PRISON DIARIES: INSIDE THE WALLS OF LONG BAY JAIL

PRISON DIARIES: MALCOLM NADEN - FROM PREDATOR TO PRISON PREY

PRISON DIARIES: EXCREMENT THROWN PAEDOPHILE ROBERT HUGHES

PRISON DIARIES: INSIDE AUSTRALIA’S HARDEST WOMENS JAIL

The first two shots struck the wagon. The next hit a human.

‘Ahhh!’ screamed Senior Constable Moran, the third shot tearing into his testicle. ‘Jesus save me! My balls — he hit me in the bloody balls!’ Moran jumped from the wagon and found cover behind the cart. ‘Ahhh!’ he screamed again, the pain of the wound on landing reaching a whole other level. Blood exploded from his lap like a geyser, his groin a busted water pipe, rushing a river of red.

The sight of his wounded colleague horrified Sargeant Condell — and then it angered him.

‘Shoot these wretches,’ Condell shouted.

‘Kill them all!’

Haviland jumped out of the wagon and took cover at the back of the cart next to Moran. He looked down at his colleague’s bloodied lap.

‘Crap,’ said Haviland. ‘We don’t get paid enough to die.’

The shooting was relentless. Bullets tore the wagon apart, smoke and splinters spewing into the air. The pair hugged their .53-calibre single-shot carbines like teddy bears. They would have just one shot — if they were crazy enough to take it.

Stealing from the rich is one thing. From the poor? Well, that’s another.

‘Wait till they reload,’ screamed Condell, attempting to be heard over the gunfire, as he positioned himself at the front of the wagon. ‘We will jump out and hit them when they are spent.’

But the shooting did not stop.

‘How bad is it?’ Haviland asked, again looking at the blood.

‘Can you fight?’

Moran took a deep breath and steeled himself, the trap ignoring the agony of the bullet fragment in his balls. He then lifted himself from the floor.

‘What choice do I have?’ Moran replied. ‘I’ll cry about it later.’ He took another deep breath, summoned all his mental strength to turn the bush blaze in his lap into a campfire.

‘There must be two groups,’ he said. ‘One by the rocks and another on the other side. The second group is firing while the first reload.’ ‘We’re screwed,’ Haviland said.

The shooting from the open stopped and a new barrage from behind the rock began. Moran dared to sneak a peek at the attackers, who were now reloading. He stuck his head out of the cover of the cart to see what they were up against, knowing full well he could be shot again.

‘There are three scamps out in the open,’ he said. ‘They are reloading.’

The bandits were heavily armed and their disguises were almost as frightening as their weapons: faces painted black, red scarves over their mouths. This was no friendly stick-up.

These bushrangers were prepared to kill.

‘Let’s just run,’ Haviland said. ‘I don’t want to die.’

‘Really?’ said Moran. ‘Leave the Sergeant?’

Haviland shrugged. ‘Better being a deserter than dead,’ he said.

Moran looked down at his wound. He wondered if he could even run …

‘I said shoot these wretches,’ screamed Sergeant Condell.

‘Shoot them or I will shoot you.’

Moran sprang into action, his brief flirtation with fleeing shattered by the shouting sergeant. He leaped from cover, carbine in hand, and, defying the agony of his wound, ran towards the reloading bushrangers. He squeezed off his one and only round. He also had a revolver, an American Colt six shot, but with a .36-calibre handgun he might as well have spat at them from there.

Haviland followed and also fired, but the panicked pair missed their men. They stopped in their tracks as they heard the Sergeant scream.

‘I am hit!’ yelled Sergeant Condell. A bullet, launched from behind the rock, had torn into his side. ‘Run!’ he screamed.

‘Go before this lot opens fire.’ Condell and Haviland took off into the bush.

‘Yeah, run, you chicken s---s!’ (John) O’Meally screamed.

‘You damn cowards!’ (Johnny) Gilbert added.

Hall cheered before launching his own victory shot into the air.

Gardiner edged forward, gun raised and two of his men on his tail.

The stagecoach had been upended. Two of the horses had bolted, scared by the blasts and just missed by bullets. A wheel had been smashed free and the metal boxes were on the ground.

The driver was lying face down on the ground, his hands behind his head. The senior constable was resting against the upturned coach. His hands were firmly in his lap.

‘Don’t shoot,’ said the trap. ‘I am unarmed. And I need help. Look. My balls.’

Hall had now moved from his rock and edged towards Gardiner and the metal boxes, the lucky dip sprawled on the ground.

‘Well, if you aim that c--- of yours like your gun they wouldn’t be any use to you now anyway,’ Gardiner said. He pointed the barrel of his 1849 Colt revolver at the officer’s face. ‘But I might let you keep your head,’ he said. ‘Okay, what we are going to do now is tie you fellas up.’ He looked down at the trap’s wound. ‘Ouch,’ he said.

The man with testicles turned to minced meat gave him a painful nod. The bearded bushranger winced before turning to the lump on his right.

‘You,’ Gardiner said to O’Meally, ‘tie them both up.’ Next he looked to Gilbert and said, ‘Get (Dan) Charters to bring the horses.’ Finally he nodded at Hall. ‘Let’s see what we’ve got,’ he said, pointing to the score.

Hall looked at the four steel boxes sitting in the red dirt next to the upturned cart. His mind wandered.

Gold. Farm. Family. Biddy. Henry.

Hall heaved a box upright, back straining as he made the lift; it was far heavier than he’d imagined.

Gardiner stood behind him. ‘Let’s open ’er up,’ he said. He pulled out the tomahawk and with a swing had smashed apart the lock. ‘Woohoo,’ Gardiner cried as he lifted the lid. ‘Would you look at that? You f---ing beauty! That’s gold, my lads.’

Hall moved in to inspect the bounty.

‘There is a quid or two here,’ he said as he looked at the gold — freshly mined nuggets of all shape and size, some mere shavings, others the size of a fist.

Gardiner beamed. ‘I told you this would be a score,’ he said. ‘Just have a look at what we’ve got here.’ The experienced thief tempered his excitement then; they still had a job to do. ‘Alright, let’s get this all loaded up,’ he said. ‘Grab their horses. We will use their nags to carry the load.’

Gardiner did not want to tire his own horses. He suspected he would need them fresh to outpace the law. And the law would come.

‘Are we going to open the other boxes first?’ asked Hall.

‘No time,’ Gardiner said. ‘Got to move.’

O’Meally had secured the driver and the trap with blasted balls. ‘What about the mail?’ he asked. ‘Are we taking it?’

This time it was Hall who spoke. ‘Let’s leave it,’ he said.

‘That belongs to people like you and me.’

O’Meally snorted. ‘But there could be a load of cash,’ he said. ‘People sending their wages to their family.’

‘And their families should get it,’ Hall said. ‘We have plenty enough from the banks. Stealing from the rich is one thing. From the poor? Well, that’s another.’

‘He’s right,’ Gardiner said. ‘No good getting the common folk offside. We are going to need all the help we can get. If they turn on us then we are done.’

O’Meally nodded. A bushranger was nothing without the protection of his people.

The gang secured the load then Gardiner grabbed at a rein, the tug starting the horse.

‘Let’s go, men,’ he said.

The posse of black-faced bandits started heading over the hill, getaway begun.

EUGOWRA, 15 JUNE 1862, 3.30PM

‘I’m going to die,’ yelped Moran, the full extent of his wound becoming apparent now the adrenaline secreted during the attack had subsided. ‘You need to find help.’

Fegan lifted his face from the dirt and looked around. The bushrangers seemed to have disappeared, so he started pulling his cramped body onto his knees. Now standing, his hands fastened firm behind his back, he looked down at the sergeant.

He did not like what he saw. Moran was bleeding out; it didn’t look like he had too long.

‘Okay,’ Fegan said, ‘there’s a station just over there. I’ll go for help.’

The men from the bullock team had vanished too.

‘I’ll be back soon,’ said Fegan. ‘Keep pressure on the wound and you will be fine. I have seen worse.’

Fegan turned and walked. ‘Ouch,’ he whispered before shaking his head.

A little later, Fegan heard hooves.

‘Here!’ he shouted, every ounce of his breath used to send his voice as far as his lungs would allow. ‘Over here!’

The rider spotted the man in his field and turned to gallop his way.

‘What’s going on?’ he asked. ‘I’m Hanbury Clements, owner of Eugowra Station. I was out with my cattle and I heard the shots. It sounded like war.’

Fegan looked up at the squatter. ‘Escort coach, we were robbed,’ said the driver. ‘Bushrangers. They came from nowhere. Eight of them, maybe more. We never stood a chance.’

‘Where are they now?’ Clements asked, waving his shotgun. ‘Did you get any of them?’

Fegan shook his head. ‘No, but the senior constable copped one in the nuts,’ he said. ‘He is in a bad way. The sergeant and the other constable went for help.’

Fegan shrugged. ‘I didn’t even have a gun. There was nothing I could have done. It was an ambush.’

Clements raised an eyebrow. ‘What about your lookouts?’ he asked. ‘What about your forward flank?’

You need to go get help. We have to get these sons of bitches.

Fegan shook his head. ‘No, it was just us,’ he said. ‘No lookouts.’

The police inspector, Sir Frederick Pottinger, had laughed when Fegan had suggested the escort’s security was lax.

‘For a load like this we might want an advanced flank,’ Fegan had said when he’d learned of the job. ‘I would also suggest a rear flank.’

‘Ridiculous,’ Pottinger had said. ‘Bushrangers attack the escort? How absurd. No one would dare attack the Crown and risk being hunted down and hanged.’

Fegan could handle arrogance, but not ignorance. ‘Well, surely the other two officers will be mounted?’ Fegan had inquired. ‘They will be able to move both ahead and back?’

‘How many horses do you think the police force owns?’

Pottinger had replied. ‘The horses are for pulling and nothing else. That would be a misuse of Crown resources, an unnecessary excess.’

Fegan had been beating a dead horse.

Clements shook his head. ‘What’s done is done,’ he said.

‘You point me to where the senior constable is and I will go fetch him. You are useless to me without a horse. Go back to the house and rest. Tell my wife what has happened and she will take you in. There will be a hot meal and a bed.’

Clements rode on and soon reached the crime scene: an upturned wagon, bullocks grazing on the produce they were supposed to cart, and a copper lying in a pool of spent bullet shells and blood.

Moran was out cold.

Clements hauled the senior constable onto his horse. He saw the wound but had nothing to stop the blood. He dug his heels into his horse and began the journey back to his house.

He suspected the big man would die on the way.

Not far from home, the makeshift ambulance was stopped by a cry.

‘Help! Over here!’

Haviland was holding up Condell, his arm tucked under a rib and using his right leg to kick him along.

‘How bad is it?’ Clements asked, looking at the sergeant.

‘You look a little better than this one.’

Condell opened his jacket to show off his wound.

‘Well, maybe just,’ Clements said. ‘Rest here. I’ll take this one back to the house for help and then come fetch you. I’ll be less than an hour.’

Condell was standing over Moran when the senior constable came to. He was tucked up in a bed, his scrotum having been cleaned, stitched and wrapped by Clements’ wife.

‘You need to go get help,’ Moran said. ‘We have to get these sons of bitches.’

Condell agreed, but he could not go himself. He again opened his jacket to look at his wound: now cleaned and bandaged, but just as sore. He called out for Clements.

‘Can we ask just one more thing?’

Clements agreed. He then mounted his horse and rode into the night.

NANGAR RANGE, 15 JUNE 1862, 5PM

Hall hitched his horse to a ghost gum. Only John O’Meally had beaten him to camp and was already pulling wooden boxes from shallow holes.

‘There is enough food to feed Sydney,’ O’Meally said. ‘How long does he think we are going to be hiding out?’

Hall was now poking kindling into gaps between the stacks of wood, having been assigned to start the fire. ‘Probably depends on how much we stole,’ he said. ‘They will send the entire force after us if there is as much gold in those other boxes as the first one. I might end up having to eat you.’

The sun had not quite set but the mountain floor five miles from the scene of their crime was in darkness. The rows of pines, gums and scrub that would hide them from the law kept out the dying breath of the sun.

(John) Bow, (Henry) Manns and (Alexander) Fordyce soon arrived.

‘You got that fire going yet, Hall?’ Manns demanded. ‘We will freeze to death if the traps don’t get us first.’

The loot followed, strapped to tired horses that had been urged on by equally exhausted men. Charters was dripping with sweat, the perspiration cutting skin-coloured rivers into his blackened face when he lobbed in. O’Meally leaped from his perch beside the firepit and tripped on a box of food as he rushed towards the bushrangers’ bounty.

‘Watch it,’ yelped Charters. ‘You will ruin the food. I’d rather be shot than starve.’

‘Just don’t break the grog,’ said Gardiner, the leader appearing with the knockabout Gilbert at his side. ‘We have some celebrating to do.’

The gang cheered and slapped each other’s backs, the relief of having made it this far sinking in.

‘Now let’s see what we have,’ Gardiner said.

The celebrations continued as the other three metal boxes were busted open. Inside were piles of gold and cash. It would later be established that the first box contained 521 ounces, the second another 129 ounces and the last held 3,700 pounds in cash. The box they had already opened contained 2,719 ounces. In total the men had seized 170 pounds of gold, now piled into potato sacks.

‘Holy s---,’ Charters said. ‘That’s more than the Victorian boys got from the bank.’

The robbery of the Ballarat branch of the Bank of Victoria was legendary. Four bold, brazen and armed-to-the-teeth bushrangers had stormed into the branch on the afternoon of 16 October 1854 and stuck up the bank. Storing riches from the nearby goldfields, the bank was an apple ready to be picked. The four gunmen had escaped with thirteen thousand pounds in cash and 330 ounces of gold. It was the biggest robbery in Australian history.

Until now …

Hall continued to work on the fire and finally a spark took to the tinder. He imagined his face on a wanted poster as he looked into the rising flame. A two-hundred-pound reward just for information about the Victorian bandits had been put up following their heist, and that was half the size of this one. He turned to look at the gold, now glittering thanks to his fire.

Gardiner went about dividing the haul into piles, eight mostly even shares. He weighed the lots, but no doubt kept a little more for himself.

‘Righto, lads,’ Gardiner said. ‘Here it is.’ He hurled a bag to O’Meally. ‘They are all the same, lads,’ he said. ‘You won’t be able to spend any of them piles in four lifetimes.’

There was laughter from around the fire.

Gardiner pulled his red scarf from his pocket and threw it into the flames. ‘You too, gents,’ he said. ‘Let’s burn anything that will connect us to the crime. Well, everything except the gold.’

The rest followed suit.

‘We leave for Mount Wheogo in the morning,’ Gardiner said.

FORBES, 15 JUNE 1862, 11PM

Hanbury Clements burst into the police station.

‘Where’s the inspector?’ he asked. ‘I need to speak to the inspector. There has been a stick-up. Two officers have been shot.’

The squatter had made the thirty-mile journey to Forbes in just three hours. A man on a mission, the moon his only light, Clements had ridden his horse to breaking point. Lash after lash, the crack of his whip sending the creature speeding headfirst into darkness.

‘Now,’ Clements demanded. ‘Your senior constable has had his balls shot off.’

Clements had their attention.

‘Settle down, mate,’ said the junior officer, ‘we hear you. We’ll go get the boss but for your sake I hope you’re not telling porkies. We are going to have to drag him from bed.’

Sir Frederick Pottinger was standing in front of Clements fifteen minutes later. Having dressed fast, eyes red and crusty, he demanded answers.

‘Balls, you say?’ Pottinger asked. ‘Shot in the testicles?’

Clements nodded and Pottinger shook his head.

‘And this was my senior constable?’

‘Yes,’ Clements said. ‘Moran. We stitched him up and he is at my station on the mend. The sergeant, Condell, gave me this.’

Sir,

About five o’clock we were attacked by a party from twelve to fifteen armed men, dressed in red jumpers, red scarves, and blackened faces. The road being blocked up with several drays, so that we had to pass close to a rock, where they were concealed, and as the coach was passing, six or seven men fired into the coach, and drew back.

Then six or seven others fired. We then returned the fire, two of the horses got wounded and started off with the coach, capsizing it and turning the escort out.

I received four bullets through the coat, one entering my left side. Senior Constable Moran received two balls, one which wounded him in the groin. The coachman receiving also two bullets but was not hurt.

The men then rushed to the coach, taking the gold boxes out, and also the mail bags, which they cut open, opening several of the letters.

I and two of the escort got to Mr Clements’ station. I requested of him to proceed to Forbes and give information.

The bushrangers were commanded by one man, who gave them orders to fire and load. I believe it to have been the voice of Gardiner, as I know his voice well. The bushrangers took two of the men’s rifles, and three cloaks which remained in the coach after it was capsized, and they also cut open my carpet bag, taking from it two shirts, three pairs of socks. I cannot identify any of them with the exception of the voice heard.

JAMES CONDELL, Sergeant

Pottinger raged.

‘Frank Gardiner,’ he screamed. ‘He has robbed the gold escort. That lunatic has shot Condell. And you can bet that Ben Hall was with him.’

Pottinger paused, attempting to collect himself. He couldn’t.

‘This is a disgrace,’ he shouted. ‘Incompetence. These cowards let Gardiner take the escort? This is unheard of. Moran is lucky his balls have been taken already.’

Pottinger bludgeoned the rest of the details from Clements.

‘We need Billy Dargin,’ Pottinger said. ‘Go and get him. I don’t care what he is doing. Just drag him in now.’

Dargin was an Aboriginal tracker. The best. He was also a precision shot and a level head. In another time Dargin would have been the inspector and Pottinger the help.

‘And go get every officer in town,’ Pottinger said. ‘We are all going. These outlaws need to be hunted down. It will be the end of us if word reaches Sydney and we haven’t locked them up. We need to get the gold.’

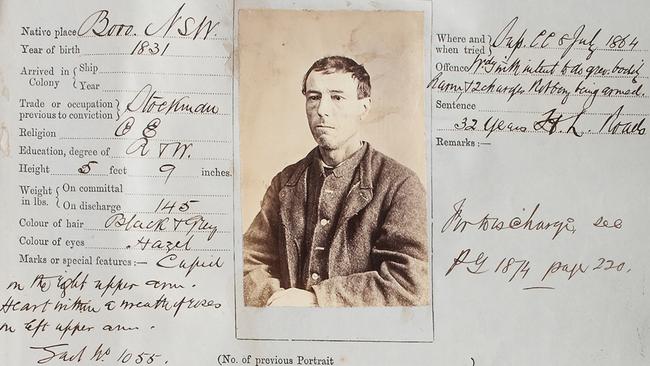

Sir Frederick Pottinger had rocketed through the policing ranks with a series of rapid-fire promotions that some would say he had not earned. Born in India in 1831, second son of Lieutenant General Sir Henry Pottinger of the East India Company, Pottinger landed in a life of privilege and wealth.

Educated at Eton, he would go on to succeed his father and inherit his wealth. But Pottinger had a weakness. He liked a punt.

After losing his family fortune at the racetrack, his mother even sold all her jewellery to help him try to pay off his debt.

He was rumoured to have lost over a hundred thousand pounds. Disgraced and still in debt, Pottinger was forced to flee England for Australia in 1856. Pottinger laid low and avoided the Sydney social set. He was determined to enter high society again, but not until he redeemed himself and made back his money.

He tried his hand at another type of gambling: gold. But as a prospector he also failed. So Pottinger joined the New South Wales police force as a lowly trooper. And there he remained until a mystery letter arrived on the desk of police captain John McLerie. Addressed to ‘Sir Frederick William Pottinger’, care of the New South Wales police. A quick search revealed Pottinger was stationed on the Burrangong goldfield.

‘Bring him to Sydney,’ ordered McLerie. ‘Now! We have a noble in out midst. A baronet can’t be a trooper.’

Pottinger — Sir Frederick Pottinger — was immediately promoted to clerk of petty sessions at Dubbo. Later that year he became the assistant superintendent of the Southern Mounted Patrol. Pottinger was a shooting star and scheduled to be promoted again, until a drunken brawl in 1861 stalled his climb.

Full of booze and arrogance, he belted a bloke in the Great Eastern Hotel, Young.

‘You’re a swindler,’ shouted Henry Cohen, slamming down his pool cue. ‘You have ripped me off.’

Cohen had just lost a game of pool to Pottinger, the renowned gambler finally winning a bet.

Pottinger cast aside his glass and picked up his pool cue.

‘Swindler?’ he shouted. ‘How dare you!’

The blow knocked Cohen to the ground. Pottinger had used the thin end of the stick, the cue more whip than sledgehammer. Cohen was dazed, his head cut and bleeding.

Pottinger then hurled the man through a window.

Cohen went on to successfully sue Pottinger for assault. He was fined a hundred pounds for the incident, but the very public affair also earned Pottinger a very public warning. His boss gave him a lashing in the press before posting him to Forbes as punishment. No lawman, at least none without a death wish, wanted to do any sort of policing in Forbes, the bushranger capital of Australia. Catch them and you were just doing your job. Fail to catch them and you were incompetent.

The other scenario, of course, was being shot dead.

Colonial Secretary Charles Cowper wrote a stinging letter to Pottinger, slamming him for being in the ‘fumes of tobacco’ and in the company of ‘the tag-end of society’.

‘Your actions were highly discreditable,’ Cowper wrote.

‘And to be occupied in gambling and betting during the whole night must unfit those who indulge in such unseemly practices for the efficient performance of their duty.

‘It occasions the Colonial Secretary considerable pain to be under the necessity of animadverting in such strong terms upon the conduct of an officer of whom he has entertained a high opinion and who has just been promoted. But, considering the state of the country more especially at the present crisis, from the large influx of diggers from the neighbouring colony and elsewhere, the officers whose particular duty it is to protect life and property, especially at the goldfields, cannot be too circumspect in their general behaviour and the Government will feel called upon to visit with the severest mark of their displeasure those who may be found acting at variance with this principal.’

Pottinger now knew his title would only get him so far. He was one f----up away from being a Sydney street beggar with a knighthood, or a bushranger’s bullet away from being buried. He didn’t know which fate would be worse.

‘And volunteers,’ Pottinger said, the second baronet knowing he would need all the help he could get. ‘Any man who can use a gun. We need as many as we can get.’

‘I’ll do my best, boss,’ said the officer.

The finest force that the western New South Wales police force could muster was assembled by 11.30pm. There were eleven troopers and two trackers. Zero volunteers.

They rode off into the darkness, every second gained on the road putting them closer to cuffing a crook.

Australian Heist by James Phelps is published by HarperCollins, RRP $39.99. Available at all good bookshops and online from Wednesday (August 1).