AT seven years old, Farhad Qaumi was a kid in Afghanistan watching Soviet fighter jets bomb his school.

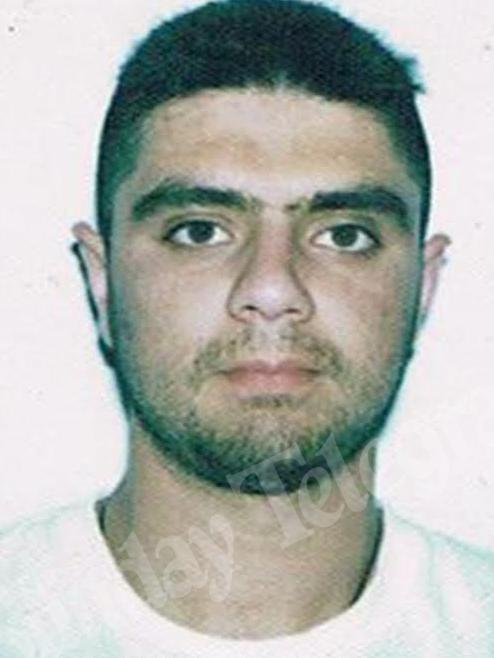

By 31, he was a supervillain: a self-styled gangster king of Sydney, charismatic and in control of the most ambitious criminal enterprise the city has ever seen.

“Put fear in a person’s heart and they’ll obey you,” Qaumi told his men, drug dealers and murderers who acted on his orders. “We’re going to give Sydney something it’s never seen.”

He was a veteran of the prison system with a storied reputation: he’d once shot a man dead and paraded the body around in the boot of his car; he’d once split a man’s head open for missing his calls; he’d pulled a gun on his father, beaten his brother to a bloody pulp, beaten charges of double murder and managed to impress members of criminal royalty in Supermax, the most high-security jail in the southern hemisphere.

It was there he met Bassam Hamzy, a Godfather-style figure who took a shine to Qaumi and his hunger for power. Hamzy recruited him to the Brothers For Life street gang with a blessing to form an aggressive new street crew.

Unleashing him would mark Sydney indelibly — and it would ultimately cause the empire to collapse. Qaumi would, in a whirl of ego and energy, bring it all crashing down upon himself.

TO understand Qaumi you have to look at his history. Police see him as a stone-cold killer but, in Qaumi’s mind, actions are justified, part of a survival story the rest of the world has never cared about. He remembers the sight and smell of bodies burning in the streets of Kandahar; seeing two Russian soldiers killed when he was on an errand to buy bread, aged six or seven. And he remembers the school bombing.

Audio: Farhad Qaumi talking to associates inside Long Bay jail in December 2013, recorded on a secret listening device. Video: Police conducting surveillance of Jamil Qaumi in Sydney, November 2013.

Audio: Farhad Qaumi talking to associates inside Long Bay jail in December 2013, recorded on a secret listening device. Video: Police conducting surveillance of Jamil Qaumi in Sydney, November 2013.

“I was sitting in my classroom and the Russians were bombing the village next to my school,” Qaumi said, via his lawyer, from prison.

“The mujahideen were holed up in the village next to my school. The (Soviets) accidentally bombed my school instead,” he said. “My teacher and close friends were killed in front of me.”

He saved his life by running to the nearest bomb shelter while the bombing continued.

Qaumi arrived in Australia in 1993 with his parents, sister and two younger brothers, after the family fled via India.

He denies, by the way, ever assaulting relatives, saying he comes from a loving family.

They were a typical refugee story of the era, settling in government housing around Auburn, an area teeming with unemployment, welfare dependency and crime.

By 14 he’d already come to the attention of authorities with a bag snatch attempt on an elderly woman in Parramatta. A spree of armed robberies would follow — a convenience store clerk, a suited man walking through a park, a passenger waiting for a train.

“Why did you kick him?” an officer asked.

“’Cause I just felt like it,” young Farhad replied. “Everyone was hitting him so I go, oh, well, why shouldn’t I hit him?”

He was ordered to attend counselling for torture and trauma survivors. The fallout from what he’d witnessed in Afghanistan was still bottled up inside him, memories that even today haven’t disappeared. He recently recalled the images of his school and dead classmates. “I was there,” he told a friend. “I was nearly fucking dead.”

By age 19 he had a criminal record. He was illiterate and working casually as a labourer. His mates were aligned to crime families with names like Zaoud and Kalache, big names in the Auburn region known to organised crime detectives. At night he cruised the streets with these friends and got pulled up by police who took down his details and, in his mind, hassled him when he was doing nothing wrong.

In October 2002 he appeared in Parramatta bail court charged with a sexual assault, an attack where police alleged that he removed an Islamic pendant to avoid disrespecting his religion. He vehemently denied the charge and insisted it was a set-up by police. The case was dropped a year later when the victim refused to give evidence.

Within a month detectives searching his car found two firearms under the passenger seat, guns that, on his account, he’d found in a park and intended to hand back to police.

During his police interview he fumed about the system working against him. He was still seething over the rape allegations and had changed his name to Billy El-Kaumi to help him try find a job and move on with his life.

“Never ever would I try to hurt anyone with a gun or even think about having a gun,” he insisted. “I’m not the type of person that would have a gun.”

A District Court judge gave him 18 months in prison, time that would end up serving as an apprenticeship. He purchased loaves of brown bread using his prison buy-ups and devoured them in his cell as a cheap way to bulk up. He learned to read. He spent his days eating, training and praying to pass the time.

When he emerged in 2005, friends immediately noticed a change in his demeanour.

Series design: Steven Grice, Andrew Belousoff.

Chapter 1: From refugee to super villain

Chapter 2: A killer on the run

Chapter 3: The killer's credo - Make men afraid

Chapter 5: When Sydney was a battlefield

Deer in the headlights or really good cop? Who is Karen Webb

Karen Webb has become our most divisive public servant since she was appointed NSW’s first female Police Commissioner in 2021. With her exit from the job looming, here’s the inside story of her time in the role.

Everyday heroes: Regional NSW residents land Oz Day honours

Not all heroes wear capes – and it couldn’t be more true for these everyday champions from Regional New South Wales who have been honoured this Australia Day. See the full list.