AT a safe house in Auburn, Qaumi handed out pistols, gloves and balaclavas to a hastily assembled shooting team.

“We only get one shot at it,” he said to his brother Jamil, giving him a gun.

The team was Jamil plus Ario, the methodic hitman, and a newly-minted gang member, Javad, recognisable by his beard and round build. The Runner drove the getaway car because they knew LC’s address at Revesby Heights.

“Run in the garage and shoot whoever,” Qaumi said as they prepared to drive.

They left Auburn in a Nissan Tiida, a rental car used for the gang’s cannabis run, driving south through Yagoona and Bankstown, then over the M5 into Revesby. Dilapidated houses gave way to palatial mini-mansions and neatly cut lawns on arrival at Bardo Circuit, a kidney-shaped street with only one entry and exit.

The gunmen peered down the street from the Tiida and saw the lights switched off in LC’s garage, which meant he wasn’t home. They pulled into a side street and waited for midnight when his bail curfew would take effect, the tension increasing as they waited: Ario said his back hurt; Jamil couldn’t work the safety catch on his gun; Javad insisted they pull out because it was all taking too long.

A half-hour’s drive away, Farhad and Mumtaz sat before a bank of poker machines at Merrylands’ Coolibah Hotel, their presence deliberate and calculated to give themselves an alibi using the venue’s CCTV cameras.

By 12.30am the lights in LC’s garage had switched on and the Tiida moved into Bardo Circuit, idling a short distance away as the shooters crept up on the property.

In the garage, Little Crazy sat around laughing and watching YouTube clips with his brother-in-law Mehmet Yarar and two cousins, Omar Ajaj and Mahmoud Hamzy. By the time they saw the gunmen, shots were already being fired. The first one hit Mahmoud’s head with a force that threw him backwards off his chair. LC and his brother-in-law fled through a door as bullets chased them. Ajaj lay on the ground and played dead until the gunmen disappeared, a final shot hitting him in the leg as the Tiida sped away.

In the car, Jamil boasted “I killed him! I killed LC!” he said, unaware the wrong man had been felled. “Did you see all the blood coming out of his head?”

They drove to a debriefing in Granville Park where Farhad was waiting with Mumtaz. He demanded details of what happened and was given assurances that LC was dead.

Fire crews would later find the Tiida’s charred husk in Penrith, with a five-litre drum of fuel sitting in the passenger seat.

By morning, news crews were filming an uninjured Little Crazy rolling up to the crime scene in a Ford Mustang and wearing a forensic jumpsuit.

“Just fireworks,” he said, smirking at reporters.

Qaumi tried to show solidarity with the Bankstown crew to throw off any suspicions they might’ve had of him. Strategic phone calls were made and condolences passed on. But within three days there was word filtering back to Qaumi that both he and his gang members were suspected of masterminding the attack.

Fearing reprisals, he called a meeting with gang members and drew up plans for a pre-emptive strategy.

“We have to retaliate before the Lebos get us,” he said.

A list of assassination targets was written up: Michael Odisho, Masood Zakaria, Khaled Hamzy, Mahmoud Sanoussi and more. Shooting squads — three men per team — were assigned and deployed.

The next day, November 3, a Lexus slowed outside the Winston Hills home of Michael Odisho, his address one of the few Qaumi knew off the top of his head. Odisho’s mother heard footsteps as two gunmen approached.

“I think someone’s here,” she whispered to her son.

A shotgun blast sprayed pellets into her arm as she looked outside. Police found Odisho in the driveway three minutes later, with a neighbour pressing a towel into his leg. Despite multiple gunshots, he survived.

The next night a shooting team hit the Blacktown home of Masood Zakaria, injuring a 14-year-old girl standing with him at the door. Her spine, lungs and chest were filled with shotgun pellets, nearly killing her and jeopardising her ability to have children.

We have to retaliate before the Lebos get us”

Police from two separate strike force teams worked overtly and covertly to stop the shootings. One team – Strike Force Roxana – focused on the Hamzy murder. Another team, Strike Force Sitella, worked to stop the shootings.

Real-time surveillance was placed on all three Qaumi brothers. Their phone calls were intercepted and officers physically followed them on the ground and from the air.

A day later Farhad booked a flight for Thailand, leaving Mumtaz and Jamil in charge. Despite being under investigation, police had visited Farhad at his home on the Central Coast and warned him to stay out of Sydney for his own safety.

By now they were aware of the gang war driving the shootings. Like Farhad, they were expecting Bankstown to retaliate.

AS detectives worked overtime, a separate crisis was hanging fog-like at the top of the NSW Police Force.

The BFL’s feuding, the nightly shootings and the injuries to a 14-year-old girl had created a political crisis for the NSW Government with flow-on effects for the choice of the next police commissioner.

Nick Kaldas and Catherine Burn, both top cops, both incredibly ambitious, were being touted to succeed the soon-to-be retiring Commissioner Andrew Scipione. Both were crucial to Scipione’s battle against gun violence but they weren’t talking to one another.

Kaldas, born in Egypt and fluent in Arabic, was in charge of Field Operations, commanding a division of 16,000 street cops and frontline commanders. Burn, a savvy tactician, was in charge of Specialist Operations, a portfolio that gave her complex investigations run by the prestigious State Crime Command.

Walls had gone up between their respective staff, creating paperwork delays that slowed down frontline police work. They smiled politely when they crossed paths, but avoided each other at “Monday Morning Church”, the Commissioner’s weekly Executive roundtable meetings.

Their dispute dated back 14 years to a top-secret investigation Burn had helped co-ordinate against allegedly corrupt officers. Part of the job had been to wiretap senior police, among them Kaldas, a clean, decorated detective, whose home, office and mobile phone were bugged, even though no corruption allegations had been made against him.

“They’re adults,” Scipione told people, refusing to intervene. “They can sort it out themselves.”

The rise of BFL and months of headlines about unrelated underworld activity had created a general feeling of discomfort in the community. Premier Barry O’Farrell appeared on the television news almost nightly to reassure viewers. Politically, pressure was building on him to do something about it.

O’Farrell viewed Kaldas as an answer to these problems. He was a respected identity in the Middle Eastern community with the operational policing and management experience to back it up.

The Premier made his views known to Scipione and not long afterwards a “functional realignment” of resources saw the State Crime Command removed from Burn’s responsibility and given to Kaldas.

Symbolically, the move was a vote of confidence in Kaldas and the implication was clear: he’d been called in to save the day.

But Scipione played down the conjecture that followed.

“The nature of crime changes and we have to change the way we approach it,” he said.

Ambush at the Chokolatta Cafe

BARELY two days after the Zakaria shooting, with retaliation expected, The Runner contacted Mumtaz with word that Bankstown BFL members were up to something.

Rumours were getting around that a Bankstown BFL ally, “Abs”, was using friends in real estate to try find the Qaumi brothers’ addresses on the Central Coast.

Already on high alert, Mumtaz called a meeting with gang members.

“We’ve got to get him before he gives the addresses out,” he said to slow-thinking Vayu, pot-smoking Pouria, and a new guy, Mohammed Kalal, the only Lebanese member of the Blacktown crew. Not much was known about Abs except that he worked at a cafe in Bankstown, the Chokolatta Café.

Undercover detectives, sensing an impending strike but unaware of the target, followed several cars that night, trying to keep up as license plates were stolen for getaway cars and guns prepared for the attack.

Not clear, however, was which carload of men would conduct the shooting. There were several on the move. Choices had to be made about which ones to follow.

As a result, there were no officers watching a blue Mazda which pulled up outside the Chokolatta Cafe at 12.15am on November 7.

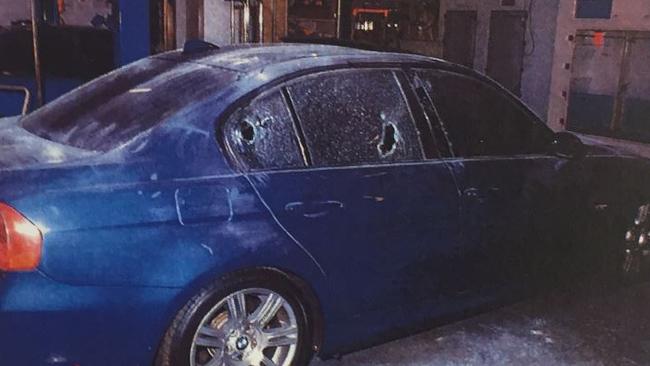

It stopped just behind a BMW in the cafe’s driveway, blocking the exit so the car couldn’t leave. Inside was “Abs” and two friends — they’d been seen leaving the cafe a few moments earlier.

With a shotgun and handgun, Kalal and Vayu went to work on the BMW, firing bullets through the windows, into the doors, standing close enough for “Abs” and his friends to hear the shotgun’s pump-action mechanism. The leather seats were smeared in blood. The driver’s headrest was torn to shreds from a direct hit.

Incredibly, no one was seriously injured.

Two detectives raced to the scene in time to see the Mazda leaving, following it for almost an hour as it drove back to Merrylands so the gunmen could drop off their weapons. A tactical team was radioed to help conduct the arrests but they got lost due to a mapping malfunction.

After much argument about whether to do the arrest themselves — they didn’t even have enough handcuffs — the two detectives pulled over the Mazda with guns drawn and pinned down the men inside until more police arrived.

Police commanders weighed up what to do about Jamil Qaumi. Was there enough evidence to charge him? Was it better to leave him on the streets and keep gathering evidence against him? Or was it better to take him out of play?

A few hours later Jamil was arrested in similar circumstances, his car followed by the Air Wing as he drove north towards the Central Coast.

More arrests would follow as the entire BFL leadership, one by one, on the Blacktown and Bankstown side, was dismantled over the following months.

Did you see all the blood coming out of his head?”

The Blacktown crew, already gutted from the Chokolatta arrests, lost Ario to a parole revocation in December. Javad would follow along with a handful of lieutenants and lower-level gang members, all of whom quickly cooperated with authorities.

Ramin rolled and told police he could get his brother, Pouria, to follow. Housed in separate jails, detectives put them in an interview room together, allowing them to reunite and have a few hours to themselves, their conversations covertly recorded.

At first Pouria baulked at the idea of assisting, but detectives made the consequences clear.

“I don’t know how long you get for shooting a young girl in her own home and riddling her so full of lead that she probably won’t be able to have children, so you should think about doing something to help yourself,” said Detective Inspector Steve Patton, leader of Strike Force Sitella.

On the Bankstown side, LC and a handful of cohorts were arrested by the Homicide Squad, as predicted, over the 2012 murder of Yehya Amood.

From prison, however, the tit-for-tat warring continued: Jamil was bashed during a run-in with Little Crazy and a house belonging to Ramin’s older brother was shot up.

Farhad, home from Thailand, retaliated with a drive-by shooting of LC’s mother’s house at Greenacre, a wayward bullet hitting a neighbour, Anthony Elkadi, as he smoked a cigarette.

But the final word went to the Bankstown crew, who closed in on Qaumi with an assassination attempt during a New Year’s Day yacht cruise on Sydney Harbour. A bullet narrowly missed his vital organs.

Unwilling to risk more retaliation, police moved on Qaumi with the evidence they had on January 8, 2014, arresting both him and Mumtaz and charging them with a handful of drug and firearm offences.

Off the streets, and with the violence minimised, detectives worked backwards through each crime, revisiting scenes and collecting statements, preparing a drum-tight case against the brothers.

Within a few months the Qaumi brothers were facing the kind of charges that could see them imprisoned for life: murder, solicit to murder, conspiracy to murder and a host of other major crimes.

Deer in the headlights or really good cop? Who is Karen Webb

Karen Webb has become our most divisive public servant since she was appointed NSW’s first female Police Commissioner in 2021. With her exit from the job looming, here’s the inside story of her time in the role.

Everyday heroes: Regional NSW residents land Oz Day honours

Not all heroes wear capes – and it couldn’t be more true for these everyday champions from Regional New South Wales who have been honoured this Australia Day. See the full list.